Elizabeth Taylor, British Novelist and Short Story Writer

By Marcie McCauley | On January 17, 2020 | Updated September 3, 2024 | Comments (2)

Elizabeth Taylor (July 3, 1912 – November 19, 1975) was a British novelist and author of short stories who is generally acknowledged to be underrated — a brilliant writer who deserves to be more widely read. She is not to be confused with the iconic actress with the same name.

Writers as distinct as Antonia Fraser, Barbara Pym, and Kingsley Amis admired her works, which are filled with impassioned as well as lonely characters.

Upbringing and Education

In 1912, she was born Dorothy Betty Coles in Reading England. She wouldn’t begin to refer to herself as Elizabeth until the early 1930s. As a child, she was very close to her mother, Elsie May Fewtrell. Her father, Oliver, was an insurance inspector.

In September 1923, Betty attended Abbey School, a well-known Christian school. Although she would later become an atheist). She struggled with mathematics but received 99% on an English paper, which was the highest mark ever received by an Abbey School student (the one percent deducted to acknowledge that everyone’s handwriting could stand improvement.

Betty officially completed school in Berkshire in July 1930 but actually had finished before the previous Christmas. Even then, at seventeen, she aspired to write. She would write about this later, in a 1951 issue of The Bookclub Magazine: “I wanted to be a novelist, but it is not easy suddenly to be that at 17. I spent a year trying to write, despairing.”

Early reading and writing

As a child, the first full-length book Betty read was Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (a book which also had a profound impact on American writer Natalie Babbitt).

She also read (and reread) the Bastable books by E. Nesbit and she enjoyed collecting comic versions of classic stories by Victor Hugo, Jules Verne, and Wilkie Collins.

As an older girl, she read Crime and Punishment, and biographer Nicola Beauman notes that Betty’s Commonplace Book, encompassing 1928 through 1936, also includes other specific works, like The Waves and To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf and Persuasion by Jane Austen.

Other authors were also recorded: Katherine Mansfield, Siegfried Sassoon, William Butler Yeats, Edward Thomas, D. H. Lawrence, Thomas Mann, and Richard Church.

As a young woman, Elizabeth often borrowed books from the Boots Libraries and, after briefly working as a governess elsewhere, she worked as a librarian under their auspices, first in Maidenhead, then in High Wycombe.

After her own work had been published, years later, Elizabeth identified specific authors as having been influential for her development as a novelist and short story writer.

The works of Jane Austen, E.M. Forster, Anton Chekhov, and Virginia Woolf were particularly important, along with Samuel Richardson, Henry Fielding, and Ivan Turgenev. Throughout her life, she would reread Jane Austen regularly: her Martin Secker set was faded and worn from frequent use.

She also remarked on the work of two contemporary writers: Ivy Compton-Burnett and Elizabeth Bowen.

Marriage, family, and love

After Elizabeth moved to Buckinghamshire, an area where the family had often vacationed, she joined the Little Theatre Club; she remained a member and performed, from 1932 to 1935, in High Wycomb.

In later years, literary reviewers and critics would comment on her ability to sketch scenes on the page, which suggests that her theatrical experience also impacted her creative work.

Another member of the troupe was John William Kendall Taylor, the man she would marry on March 11, 1936 in Caxton Hall, Westminster. This year – 1936 – was particularly significant for Elizabeth. She also joined the Communist Party (in response to concerns about rising unemployment rates and the rise of fascism), lost her mother, had a miscarriage, and she met Ray Russell.

With John Taylor, Elizabeth had a son and daughter: Renny and Joanna, in 1937 and 1941 respectively. While married, however, she had an ongoing – but intermittent – romantic involvement with Ray Russell (although he was away, and a prisoner of war, for four years during WWII).

The letters Elizabeth and Ray wrote were a primary source for Nicola Beauman’s biographical research for The Other Elizabeth Taylor (2009).

“I am always disconcerted when I am asked for my life story, for nothing sensational, thank heavens, has ever happened,” Elizabeth explains in a 1953 article for the New York Herald Tribune.

She elaborates: “I dislike much travel or change of environment and prefer the days (each with its own domestic flavor) to come round almost the same, week after week. Only in such circumstances can I find time or peace in which to write.”

First novel and adjusting to the writing life

While her husband was away in the Royal Air Force, Elizabeth wrote At Mrs. Lippincote’s, which was published in 1945. After Patience Ross at A.M. Heath secured a publisher for this debut novel, Elizabeth immediately began to work on her next.

She wrote slowly, in longhand. “When at the end of the war, I first had a novel published,” she outlines in the Herald Tribune article, “I received the proofs in trembling excitement. Now I am filled with anxiety, for I am a poor proof-reader.”

In 1949, in a letter to novelist Elizabeth Bowen, Elizabeth writes: “My hands become ice at the thought of my book [her fourth, The Wreath of Roses] being published, and I do hope that, like silicosis, it is an occupational disease; though not such a distressing one.”

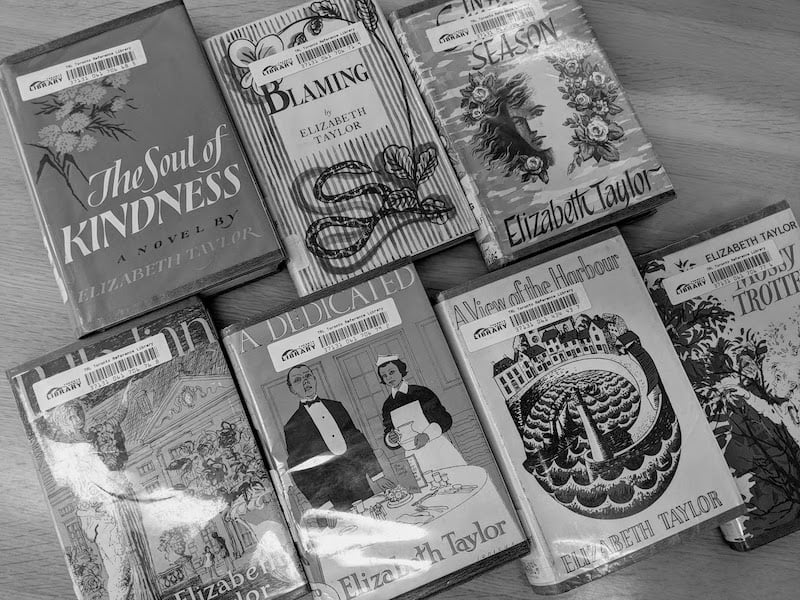

Anxious or not, Elizabeth would publish seventeen volumes in total: four collections of stories, one children’s book in 1967 (Mossy Trotter), and twelve novels, one posthumous – Blaming (1976).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Creative inspiration

In Contemporary Novelists, Elizabeth explains her process: “I write in scenes, rather than in narrative, which I find boring. I am pleased if the look of a page is interesting, broken by paragraphs or dialogue, not just one dense slab of print.”

And she speaks about the driving force of characterization in her work, in a letter to Blanche Knopf, her American publisher, in October 1948:

“People are my only adventures and I hope never to have any others; and, though I do not use their characters in my books, their company constantly replenishes me and inspires me. To be allowed to be ‘ordinary’ and live among ‘ordinary’ people (though no one is really that) is the only way that I can write, and I expect that this limits my range; but I have no gift for anything else.”

One exception, however, is Elizabeth’s 1957 novel, Angel, which was inspired by her reading of two biographies of the popular English novelist Marie Corelli, one by Eileen Bigland published in 1953 and the other by Amanda McKittrick Ros published in 1954.

In his 1995 introduction to A View of the Harbour, originally published in 1947 and later reprinted by Virago Books, Peter Kemp also observes the importance of artists in Elizabeth’s works. Particularly in A Wreath of Roses (1949) The Wedding Group (1968), and Blaming (1976), artists play a prominent role.

Artists who capture everyday life

In a 1948 letter to Ella Bellingham-Smith, Elizabeth praises her paintings as viewed in the artist’s first solo exhibition at the Leicester Gallery that year:

“I feel in all you paint, your tenderness, your modesty. I know that that is how children stand, and move, and group themselves. And the weather is constantly changing everything, and each hour of the day has its especial quality.”

As Paul Bailey later describes, in his introduction to Virago’s reissue of The Blush (first published in 1958 and reprinted in 1986): “The quotidian is Elizabeth Taylor’s province, where the ordinary are to be found extraordinary, as she thought they should.”

Brigid Brophy, in her 1966 collection Don’t Never Forget: Collected Views and Reviews, describes Elizabeth Taylor’s uncanny capacity to encapsulate everyday details: “Mrs Taylor’s mastery is such that she can express her characters’ feelings about one another through their exasperation with one another’s children and chows.”

A talent for short stories

Elizabeth’s first published work was a short story in Tribune, “For Thine is the Power,” which appeared March 31, 1944. It was accepted by George Orwell, the new literary editor, having been rejected by Reginald Moore at Modern Reading the previous year.

Another story, “Better Not,” had been accepted first, but it was not published until later in 1944 in The Adelphi, edited by John Middleton Murry.

Paul Bailey, who contributed the introductions to many of Virago’s reissues of Elizabeth’s work, describes her particular talent with stories: “The short-story form is one that attracts the swift glance rather than the long, cold stare, and Elizabeth Taylor is one of the great glancers.”

Robert Liddell, who would later write about his friendship with Ivy Compton-Burnett and Elizabeth Taylor in his memoir Elizabeth and Ivy (1986), observes some autobiographical elements in her short stories. He points, for instance, to “The Letter Writers,” a story about Edmund and Emily, who have been corresponding for ten years (as, indeed, Robert and Elizabeth had been, when she wrote this story): letters provide the foundation of their friendship, despite never having met in real life.

Elizabeth’s collections appeared throughout her career: Hester Lilly (1954), The Blush (1958), A Dedicated Man (1965), and The Devastating Boys (1972).

Alongside these volumes, Elizabeth also published regularly in The New Yorker, beginning with an excerpt from A View of the Harbour (1947) the year after the novel’s publication. At that time, she worked with Katharine White, and later and until 1969, with William Maxwell.

The last short story she completed was written in the hospital, while she was recovering from a cancer-related surgery: “Madame Olga,, which was published in August 1973 in McCall’s.

Posthumously, Virago published her Collected Stories in 2012: this marked the centenary of her birth and included the stories previously only published in The New Yorker.

Also in 2012, Cambridge Scholars Publishing issued Elizabeth Taylor: A Centenary Celebration, which includes some non-fiction articles, as well as two story fragments (unfinished and unpublished in her lifetime) and some academic studies.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Taylor’s Novels: Where to Begin, Which to Re-read

. . . . . . . . . .

Peer recognition and community

Novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard first met Elizabeth Taylor as part of the publicity for In a Summer Season (1961). Howard had prepared thirty questions for an eight-minute interview, anticipating that would be more than sufficient, but Elizabeth so quickly dispatched those queries, with ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answers, that Howard’s questions were exhausted in under two minutes.

Elizabeth was notoriously private and respected other writers’ privacy as well. When asked by her American publisher to prepare an article about Ivy Compton-Burnett, Elizabeth compiled a biographical sketch, overlooking the fact that she was given the project because she had become friends with Ivy and, as such, was expected to share personal anecdotes and provide lesser-known details about her.

Elizabeth’s writing was not universally admired, however. During her lifetime, Robert Liddell identified what he referred to as the “Lady-Novelists Anti-Elizabeth League” — said to include Kay Dick, Kathleen Farrell, Kate O’Brien, Pamela Hansford Johnson, Stevie Smith, and Olivia Manning, all of whom disparaged her work.

In 1952, Elizabeth was included in England’s Who’s Who and, in 1966, she was declared a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In between, her husband’s confectionary business sold, the couple’s son and daughter each married and each had had their first child – Joanna’s in 1964 and Renny’s in 1967, and Elizabeth’s affair with Ray had ended.

In 1971, Elizabeth’s novel Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, along with works by V.S. Naipaul, Derek Robinson, Thomas Kilroy, Mordecai Richler and Doris Lessing).

Elizabeth Taylor’s Legacy

In Sam Jordinson’s 2012 article “Rediscovering Elizabeth Taylor – the brilliant novelist” (The Guardian), both Paul Bailey and Elizabeth Jane Howard declare themselves envious of “any reader coming to her for the first time.” Here, Antonia Fraser identifies her “one of the most underrated writers of the 20th century.”

Hilary Mantel said that she is “deft, accomplished and somewhat underrated,” and Rosamund Lehmann describes her as “sophisticated, sensitive and brilliantly amusing”.

Consider, too, Joyce Carol Oates’s comments in theWashington Post in 1972:

“There is a distressing similarity between Taylor’s many stories – an assumption, which sometimes destroys a reader’s enjoyment of her art, that the people she deals with in her fiction are not people, but characters. They are imagined as interior creations, existing within the confines of their particular stories; and they are made to be, and even to feel, inferior.”

But for every dismissal, there is a comment like Kingsley Amis’s in The Statesman in 1971:

“Mrs Taylor is one of those novelists who look homogeneous, as if working within a single mood, and turn out to be varied and wide-ranging. There is a deceptive smoothness in her tone, or tone of voice, as in that of Evelyn Waugh; not a far-fetched comparison, for in the work of both writers the funny and the appalling lie side by side in close amity.”

Elizabeth Taylor continues to find new audiences, thanks to reissues from Virago and NYRB. From 2012 to 2014, BBC selected some of her short stories for broadcast and, more recently, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont was a Book at Bedtime, read by Eleanor Bron, in 2018.

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont was also made into a 2005 film (directed by Dan Ireland – from a screenplay by Ruth Sacks Caplin written for television in the 1970s – and starring Joan Plowright). And Angel was filmed in 2007 (directed by François Ozon and starring Romola Garai).

Her stories continue to resonate with readers today.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Elizabeth Taylor

On this site

- Elizabeth Taylor’s Novels: Where to Begin, Which to Re-read

- Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor’s Fiction

- Quotes by Elizabeth Taylor on Love and Loneliness, Beauty and Marriage

Major Works

Novels

- At Mrs. Lippincote’s (1945)

- Palladian (1946)

- A View of the Harbour (1947)

- A Wreath of Roses (1949)

- A Game of Hide and Seek (1951)

- The Sleeping Beauty (1953)

- Angel (1957)

- In a Summer Season (1961)

- The Soul of Kindness (1964)

- Mossy Trotter (1967; her only children’s book)

- The Wedding Group (1968)

- Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont (1971)

- Blaming (1976; posthumous)

Short story collections

- Hester Lilly (1954)

- The Blush and Other Stories (1958)

- A Dedicated Man and Other Stories (1965)

- The Devastating Boys (1972)

- Dangerous Calm (1995)

- Complete Short Stories (2012)

- Elizabeth Taylor: A Centenary Celebration (2012)

- You’ll Enjoy It When You Get There: The Stories of Elizabeth Taylor (2014)

Biographies

- Nicola Beauman, The Other Elizabeth Taylor (Persephone Books 2009)

- Elizabeth and Ivy, ed. Robert Liddell (1986)

Film adaptations

- Angel (2007)

- Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont (2005)

More information and sources

- “You May Have Heard of Her” by Christopher R. Beha

- “The Other Liz Taylor” by Philip Hensher

- “The Other Elizabeth Taylor” by Benjamin Schwarz

- “How the Other Elizabeth Taylor Reconciled Family Life and Art”by Namara Smith

- Reader discussion of Elizabeth Taylor’s books on Goodreads

- Wikipedia

I read so many years back a book by the topic The Writing Business by Liz Taylor. The author, according to the book, studied history in college/university. Her history background and The Writing Business had never been mentioned in your story.

It was likely a different Liz Taylor, as this one went only by the name Elizabeth and published only fiction. I couldn’t find anything in conjunction with this author and the title you mention!