Barbara Pym, British Author of Comedies of Manner

By Marcie McCauley | On October 10, 2019 | Updated August 23, 2022 | Comments (2)

Barbara Pym (Barbara Mary Crampton Pym; June 2, 1913 – January 11, 1980) was a British author whose novels explored manners and morals in village life with a subtle, understated wit. She published nine novels in her lifetime and four books were published posthumously.

Tweed skirts and peach halves, knitted socks and tea kettles, macaroni cheese and old books: Barbara Pym has become known for her novels about the small comforts of mid-twentieth-century Englishwomen’s daily lives.

Much as Belinda turns the conversation to lighter topics in Barbara Pym’s first published novel, Some Tame Gazelle (1950), to avoid argument and taking things too seriously, Pym’s fiction appears to focus on lighter matters.

She appears to be concerned with whether to serve a rich fruit cake or a cake with a coffee icing or with who knits socks for whom, but these details reveal deeper truths about how people forge and maintain connections, and what happens when those efforts fail and people live solitary lives.

Upbringing and education

Born in the small market town of Oswestry, in Shropshire, her father, Frederic Crampton Pym, belonged to a professional class, as a lawyer in a firm of solicitors. Her mother, Irena Thomas, was the assistant organist at the church they attended and was a handsome, “tomboyish” woman, according to Hazel Holt, friend and co-worker (and, later, the literary executor of Barbara Pym’s will).

At the age of twelve, Pym attended Huyton College in Liverpool, a boarding school for girls. There she read Aldous Huxley’s Crome Yellow and determined that she would become a writer. Holt recalls her early creative work, at the age of sixteen, as “respectable but adolescent”.

From 1931 to 1934, she studied at St. Hilda’s College (Oxford) graduating with a BA (Honors) in English. In A Mind at Ease, Robert Liddell recalls her as a student: a “cheerful, romantic outgoing girl of just nineteen, playfully flirtatious, whose interest in men was keen but not obsessive.”

She met her steadiest love interest there, in 1932: Henry Harvey, who later married (and divorced) another woman, Elsie Godenhjelm. She had a string of suitors but, according to Holt, she tended to pursue “safe” romances.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Quotes from Excellent Women and other novels by Barbara Pym

. . . . . . . . . .

A Young Writer at War and at Work

From 1934 to 1939, Pym was living at home and reading widely. She particularly loved poetry and describes in “Finding a Voice” her discovery of Elizabeth von Arnim as a revelation (particularly The Enchanted April and The Pastor’s Wife), for von Arnim’s “dry, unsentimental treatment of the relationship between men and women.”

Other writers she considered influential included Ivy Compton-Burnett (for her “precise, formal conversation”), John Betjeman (for his “glorifying of ordinary things and buildings”), Gertrude Trevelyan (for Hothouse, which made her long to write an Oxford novel), and Denton Welch (for Maiden Voyage, which reflects his “acute miniaturist observation and vibrant interest in everything he saw”).

Early in the war years, Pym helped her mother care for six children who had been evacuated from Birkenhead. Shortly afterward, she volunteered at the local YMCA camp for soldiers and then began working at the Postal and Telegraph Censorship in Bristol, which suited her inquisitive personality.

She joined the Women’s Royal Navy Service in 1940 and travelled to Naples, where she served as an officer (an experience characterized by nightly cocktail parties and minor romances, Holt explains).

After the war and following her mother’s death from cancer, Pym began work at an anthropological foundation – the International African Institute – in 1946.

Just two years later, she was promoted to the position of research assistant there. She was writing in the evenings and on weekends, continuing work on the draft she began after graduation, a novel about two middle-aged sisters sharing a home.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early publications: a subtle world-building

Drawing on her relationship with her younger sister, Hilary, Pym published Some Tame Gazelle in 1950, which considered the youth and middle years of Harriet and Belinda Bede.

Straight away readers recognize the importance of church personnel in the lives of these women, which reflected Pym’s younger years, in which much of the family’s social life revolved around the church calendar. Church men come for tea and stay for cake – and an occasional nap. As Belinda observes:

“Of course, if the Archdeacon had not been asleep, she could have had some conversation within, but it was nice to know that he felt really at home, and she would not for the world have had him any different.”

These are not idealized, sacred figures: their religiosity takes a back seat to their main-dish and dessert preferences.

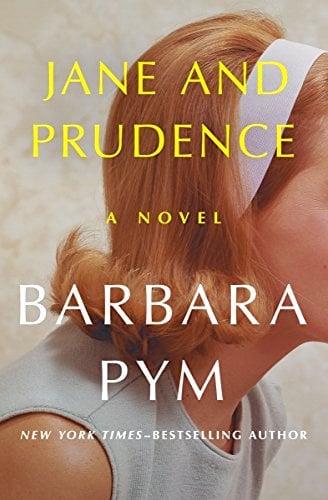

Pym published three more novels in quick succession (Excellent Women in 1952, Jane and Prudence in 1953, and Less than Angels in 1955) before she was promoted to editorial secretary and assistant editor of Africa (a quarterly publication of the anthropological institute) in 1958.

That same year she published A Glass of Blessings, notable for its unambiguously gay characters and for its reference of a character in her previous novel, illuminating a subtle world-building designed to please her growing body of readers.

Her work at the International African Institute fueled her interest in the worlds of academics and anthropologists: people studying people. In “The Quest for a Career,” Constance Malloy describes how Pym and Hazel Holt would invent “home lives” and “field lives” for their co-workers.

Holt describes Pym’s working years from 1946 to 1974, in “The Novelist in the Field” and explains that only “occasionally, when she had an idea or when things were a little slack, she would write a bit of a novel in the office”.

Pym chose to work from 10 am to 6 pm in the offices in St. Dunstan’s Chambers, so that she could avoid the 5 o’clock rush on the subway, so it’s easy to imagine that there were a few slack evenings while her colleagues were already en route in the crowds.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A disruption and renewed recognition

After her next novel, No Fond Return of Love (1961), which Holt believes to contain the most Pym-like character of all (Dulcie), Pym’s publisher lost interest in her work. Rejections accumulated and concerns about salability surfaced. She continued to write for her own satisfaction, but even after finishing three complete drafts, publishers kept their distance.

In the interim, she was diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer and she suffered a minor stroke. Still, she wrote. “Often she would get out one of the spiral-backed notebooks in which she recorded her observations and make a note of something that had caught her attention,” Holt remarked.

In 1977, in a special issue of the Times Literary Supplement which considered the “most underrated writer” of the previous 75 years, two writers, Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil, named Barbara Pym. Larkin wrote, “I’d sooner read a new Barbara Pym than a new Jane Austen.”

Publishers’ interest was renewed and her public work resumed with A Quartet in Autumn (1977).

Her books still considered anthropology and the church and also reflected her developing interests in local history and healthcare. Of these later novels, Holt refers to Letty’s character in Quartet in Autumn as the closest to Pym, as she was in the early 1960s. It was followed by The Sweet Dove Died (1978) and A Few Green Leaves (1979).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Barbara Pym’s legacy and posthumous publications

In a letter to a friend in 1976, Pym commented: “And what could be more mundane than trying to type a novel.” (This is quoted in Deborah Donato’s Reading Barbara Pym.)

Pym was not aiming to chronicle the lives of extraordinary adventurers. As Shirley Hazzard describes it: “She is herself the poet of the lonely, the virtuous, the ironic; of the unostentatiously intelligent and witty; of the angelically self-effacing, with their diabolically clear gaze. Nothing escapes such persons; and they escape nothing.”

The novels published in her lifetime are considered the Pym canon, with many devotees citing Excellent Women as their entry-point or favorite. Four additional works were published posthumously – An Unsuitable Attachment (1982), Crampton Hodnet (1985), An Academic Question (1986) and Civil to Strangers (1987) – and excerpts from her diaries and letters were published as A Very Private Eye (1984).

Pym was often compared to Jane Austen for her comedies of manner; she was called Britain’s “other Jane Austen” or “new Jane Austen.”

In an homage to Pym in the New York Times (August 24, 2017), Matthew Schneier wrote:

“Barbara Pym, the midcentury English novelist, is forever being forgotten, and forever revived. Her novels sketch a circumscribed scene whose anchors were the church and the vicarage, and the busy, decent Englishmen and -women (more women) who shuffled between the two. To read her, one must have an appetite for endless jumble sales and whist drives, and the interfering wisdom of dowagers and distressed gentlewomen.”

Barbara Pym died in Oxford on January 11, 1980, at the age of sixty-seven.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint. The Toronto Public Library played a vitally important role in the research for this piece, including assistance from the staff, in particular Leigh Turina and her onsite colleagues.

More about Barbara Pym

On this site

Major Works

- Some Tame Gazelle (1950)

- Excellent Women (1952)

- Jane and Prudence (1953)

- Less than Angels (1955)

- A Glass of Blessings (1958)

- No Fond Return of Love (1961)

- Quartet in Autumn (1977)

- The Sweet Dove Died (1978)

- A Few Green Leaves (1980)

- An Unsuitable Attachment (written 1963; published posthumously, 1982)

- Crampton Hodnet (written around 1940, published posthumously, 1985)

- An Academic Question (written 1970–72; published posthumously, 1986)

- Civil to Strangers (written 1936; published posthumously, 1987)

Biographies

- A Lot to Ask: A Life of Barbara Pym by Hazel Holt (1990)

- Barbara Pym: A Very Private Eye by Barbara Pym (1984)

- A la Pym: The Barbara Pym Cookery Book by Hilary Pym and Honor Wyatt (1995)

More information and sources

- The Barbara Pym Society

- Marvelous Spinster Barbara Pym At 100

- Barbara Pym and the New Spinster

- In Praise of Barbara Pym

- BBC’s Desert Island Discs with Barbara Pym in 1978

- An Experiment with the Barbara Pym Cookbook

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion of Pym’s work on Goodreads

Thank you so much for adding Barbara Pym. I re-read Excellent Women at least once a year. I’ve often wished that PBS would film one of her books- no nothing much happens but the characters are amazing.

It has been ages since I read her, but the enthusiastic response to this post is a reminder to re-read! I’ll start anew with Excellent Women. Thanks for your comment!