15 Classic Women Authors, 15 Lessons for the Writing Life

By Nava Atlas | On October 21, 2017 | Updated November 13, 2024 | Comments (4)

Learning how to stay disciplined, grappling with doubt, failure, and rejection, finding one’s voice, struggling to stay solvent—we’ve all dealt with these issues. It’s comforting to know that classic women authors like Charlotte Brontë, George Sand, Louisa May Alcott, and others did, as well — and their advice on writing also applies to many life situations as well.

In the end, it’s not so much about facing obstacles that matters — everyone experiences bumps in the road — but overcoming them with grace and courage.

While researching The Literary Ladies’ Guide to the Writing Life, I delved into the letters, journals, and memoirs of classic women authors. I found that certain challenges were just as universal among those who eventually became literary icons as they are among today’s writing women, whether seasoned or aspiring.

Here are 15 nuggets of wisdom I gleaned from each of the classic women authors highlighted in the revised and updated 2023 edition. Even if you’re not a writer, you can apply much of this wisdom to many aspects of life.

Literary Ladies Guide to the Writing Life (Blackstone Publishing, revised and updated 2023 edition) is available on Audible, Apple, Libro.fm, and wherever audiobooks can be downloaded. Please note: If you purchase this title from Audible, the accompanying PDF will be available in your Audible Library along with the audio.

. . . . . . . . . .

Don’t be overly modest

In popular imagination, Jane Austen is a demure, frilly cap-wearing artiste, hiding her writing efforts under a blotter. In truth, her family recognized her talent and were invested in seeing her work in print, as was she. Jane was as keen on enjoying monetary rewards and finding an audience as the next writer—male or female. “I cannot help hoping many will feel themselves obliged to buy it,” she said of Sense and Sensibility.

Of her most iconic female character, Elizabeth Bennett, she wrote, “How I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her … I do not know.” Perhaps we ascribe false modesty to our literary role models to feel better about our own.

. . . . . . . . . .

Honor the money you earn

Louisa May Alcott was determined to make a living as a writer at a time when it was challenging enough for women to earn a living wage. She accounted for every penny earned and spent, and always tried to save for a rainy day.

Louisa made monetary compensation a priority in a way that many writers — male or female — still don’t. Because creative work is often so poorly paid, it’s accepted that it’s fine to write for love rather than money. Perhaps this is a healthy acceptance of a reality. But another reality is that many writers would like to be paid for what they do — fairly, if not handsomely.

Once she became wealthy, after decades of toil, she wrote that she found her “best success in the comfort my family enjoy; also a naughty satisfaction in proving that it was better not to ‘stick to teaching’ as advised, but to write.” I suspect more of us are keenly aware of money coming in; but money going out, not so much.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Don’t sit idly by waiting for a response

Keep working, like Charlotte Brontë did, as her first novel, The Professor, made its rounds. “The Professor had met with many refusals from different publishers, some, I have reason to believe, not over-courteously worded in writing to an unknown author, and none alleging any distinct reason for its rejection.

Fortunately, she didn’t allow the “chill of despair” that set into her heart when her first effort “found acceptance nowhere, nor any acknowledgment of merit” quash her dreams of becoming an author.

She worked on something new, even as her sisters found a home (though not a good one, as it turned out) for their novels — Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey. And what Charlotte busied herself with was Jane Eyre, which found favor with a publisher that saw promise in The Professor. Jane Eyre was an immediate sensation upon publication. Read more about The Brontë Sisters’ Path to Publication.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Revise, rewrite, and revise some more

Gwendolyn Brooks dedicated her life to the art of poetry. Her works included sonnets and ballads as well as blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lyrical, book-length poems. Though her work reflected Black urban life, its underlying themes were universal to the human experience. This abundantly recognized and awarded poet wasn’t afraid to put lots of muscle into revising and polishing. It’s all part of the process. You can apply her wisdom on writing poetry to any sort of prose!

A poem rarely comes whole and completely dressed. As a rule, it comes in bits and pieces. You get an impression of something, and you begin, feebly, to put these impressions and feelings and anticipation or remembering into those things which seem so common and handleable — words.

And you flail and you falter and you shift and you shake, and finally, you come forth with the first draft. Then, if you’re myself and if you’re like many of the poets that I know, you revise, and you revise. And often the finished product is nothing like your first draft. Sometimes it is. (—from a 1979 interview)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Set your intention, and don’t waver

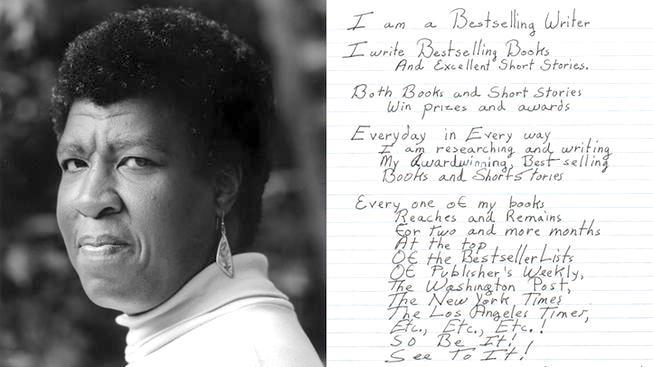

Octavia E. Butler’s mother wanted her to become a secretary. But she was determined to write, taking on odd jobs that wouldn’t drain the mental energies needed for writing. She became rigorously disciplined and stuck to a strict schedule, sometimes rising at 2:00 am to write for several hours before going to work.

She was a huge list-maker, goal-setter, and self-motivator. In A Handful of Earth, a Handful of Sky, a book on Octavia’s creative process, Lynell George observed that she “lined up her wishes and intentions. In felt-tip pens, in pencil or ballpoint on notepaper, she articulated her desires … These wishes were part of her day-to-day work, along with her daily goals and page counts.”

Rigor and practicality were central to Octavia’s practice, as was the practice of visualizing what she sought to manifest. One of her most oft-repeated mantras was: “I shall be a bestselling writer. I will find the way to do this. So be it! See to it!”

. . . . . . . . . .

Unearth your true voice — then use it

Willa Cather accepted that beginning writers, herself included, go through a stage of overwrought excess. I’ll let Willa speak for herself, as she was very fond of doing. This is from a 1915 interview:

When I was in college and immediately after graduation, I did newspaper work. I found that newspaper writing did a great deal of good for me in working off the purple flurry of my early writing. Every young writer has to work off the “fine writing” stage. It was a painful period in which I overcame my florid, exaggerated, foamy-at-the-mouth, adjective-spree period.

I knew even then it was a crime to write like I did, but I had to get the adjectives and the youthful fervor worked off. I believe every young writer must write whole books of extravagant language to get it out. It is agony to be smothered in your own florescence, and to be forced to dump great cartloads of your posies out in the road before you find that one posy that will fit in the right place…

. . . . . . . . . .

Guard your time jealously

But if you don’t value your writing time, others won’t either. Edna Ferber was a model of self-discipline. Heed her advice: “The first lesson to be learned by a writer is to be able to say, ‘Thanks so much. I’d love to, but I can’t. I’m working.”

Especially when we’re working on something that isn’t yet earning money, it’s easy to let ourselves off the hook and say yes to every request and any invitation that comes our way. Edna also recommended taking a one-day-at-a-time approach to writing time management:

It is better to think of a novel or any long piece of work as a day-to-day task to be done, no matter how eagerly you may think ahead (when you’re not actually putting words to paper) to the chapters not yet written. It is a long journey, to be undertaken sometimes with hope and confidence and high spirits, sometimes with despair. If one thinks of it in terms of four hundred — four hundred and fifty — five hundred pages, one can drown in a morass of apprehension. So one step after another, slowly, painfully, but a step. And so it grows.

. . . . . . . . . .

Take risks, or you won’t grow

Madeleine L’Engle, the author of countless sci fi/fantasy books for middle grad and YA readers (equally enjoyable for adults) faced an enormous amount of rejection, especially for A Wrinkle in Time (which, once it became incredibly successful, was also widely banned and challenged).

But Madeleine reminds us that in order to succeed, we can’t be afraid to fail. When risk is avoided, there’s less chance of failure, and even less of smashing success. Risk avoidance also prolongs lingering in one’s comfort zone — which can be quite cozy, but in the end can feel constraining. She reminds us:

Risk is essential. It’s scary. Every time I sit down and start the first page of a novel I am risking failure. We are encouraged in this world not to fail … We are encouraged only to do that which we can be successful in. But things are accomplished only by our risk of failure. Writers will never do anything beyond the first thing unless they risk growing. (—from Madeleine L’Engle Herself, 2001)

. . . . . . . . . .

Don’t keep your stories locked inside you

Many of us who write have an essential story to tell; we put it off for one reason or another — lack of time, lack of readiness, lack of courage. The story wants to be told, and we can’t; it’s agonizing. Zora Neale Hurston experienced how it felt to have a story locked inside, while lacking the confidence to bring it to life. That was her experience with Their Eyes Were Watching God, which turned out to be her masterwork.

“It is one of the tragedies of life that one cannot have all the wisdom one is ever to possess in the beginning,” she wrote. “Perhaps it is just as well to be rash and foolish for a while. If writers were too wise, perhaps no books would be written at all … There is no agony like bearing an untold story inside you.”

What is the story you have inside you? It may not feel like the right time or that you will actually pull it off, but unless you put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard, you’ll never find out.

. . . . . . . . . .

Keep rejection to yourself

and don’t let it stop you

L.M. Montgomery experienced her fair share of rejection before finding success with Anne of Green Gables : “At first I used to feel dreadfully hurt when a story or poem … came back, with one of those icy little rejection slips. But after a while I got hardened to it and did not mind. I only set my teeth and said, ‘I will succeed.’”

Montgomery decided not to share her “rebuffs and discouragements” with the world, but was determined to just keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Still, she nearly gave up and placed the worn Anne manuscript in a hatbox and gave up. After it languished in a freezing attic for nearly a year, Maud, as she was known to her familiars, decided to give it one more shot, sending it to Boston publisher L.C. Page. The Anne of Green Gables series has brought joy to generations of readers for generations. What if its author hadn’t decided to dust off the manuscript and give her dream another shot?

. . . . . . . . . .

Don’t be afraid you’ll run out of material

Anaïs Nin experienced her writing practice as a grand passion, and a path to delving deeply into the self. Her writings foreshadowed the immediacy of today’s confessional forms of memoir and blogging. Best known for her multi-volume Diary series, which became a touchstone of feminist thought, she also broke ground as a writer of female erotica and was a splendid essayist.

She recognized that within the fervent writer, there is an endless supply of material, never to run out: “The deeper I plunge, the more I discover. There is … no limit to the acrobatic feats of my imagination.” And further, “… you don’t write for yourself or for others. You write out of a deep inner necessity. If you are a writer, you have to write, just as you have to breathe, or if you’re a singer you have to sing.”

Brenda Ueland, author of the 1934 classic If You Want to be a Writer concurred: “If you are to be a writer who writes, you will never be finished … always there will be something more to write.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Be passionate about life and creating

Many women live and write in measured ways, but not George Sand (the nom de plume of Amantine Aurore Lucile Dupin). She wrote more than seventy novels, plus scores of plays, essays, and articles, all the while enjoying traveling, smoking from her hookah, and cross-dressing. She was a conflicted mother, but a doting grandmother. And she had a bazillion lovers. Sand never did anything by halves, in life or art:

I am more than ever intent upon following a literary career. In spite of the repugnance which I sometimes experience, despite the days of idleness and fatigue which cause me to break off my work, in spite of the life, more than quiet, which I lead here, I feel that henceforth my existence has an aim. I have a purpose in view, a task before me, and, if I may use the word, a passion. For the profession of writing is nothing else but a violent, indestructible passion. When it has once entered people’s heads it never leaves them.

We’d all do well to feel the passion in our lives and work, whatever that might be.

. . . . . . . . . .

Life is messy and occasional tragic —

creating is healing

Harriet Beecher Stowe lost four of her seven children at various stages of her life; despite crushing grief, writing apparently kept her sane, and definitely kept her family solvent. It was the loss of her little son that nearly destroyed her, yet was the impetus to write a long-cherished desire to write a book that would sway public sentiment about slavery:

I had two little curly headed twin daughters to begin with and my stock in this line has gradually increased until I have been the mother of seven children, the most beautiful and most loved of whom lies buried near my Cincinnati residence. It was at his dying bed and at his grave that I learned what a poor slave mother may feel when her child is torn away from her.

Though she bemoaned constant daily disruptions, she was determined to write. She accomplished it by getting what meager help she could afford (her minister husband was no help with the children and strictly by devoting “about three hours per day in writing.” The book that shook the world, of course, was Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

. . . . . . . . . .

Don’t let lack of confidence derail you

Edith Wharton, born into a wealthy Old New York family, had every advantage in her privileged upbringing — except one. Her snooty society family and friends looked down on her desire to write. It was improper. So she struggled mightily with lack of self-confidence, just like the rest of us, believing she would never be taken seriously in literary circles.

She couldn’t have been more amazed when doors opened to her. And they didn’t open because she was an heiress, but because she was a damned good writer. “My long experimenting had resulted in two or three books which brought me more encouragement than I had ever dreamed of obtaining,” she wrote.

In her early days as a writer, little could she have imagined that Henry James would become one of her BFFs, valuing her friendship and correspondence as much as she did his. She won a Pulitzer Prize for the novel, and was the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate!

. . . . . . . . . .

Embrace your inner critic

Virginia Woolf’s inner critic was active and noisy. She allowed her doubts to bubble to the surface in her journal, but they drove her to do better, rather than crush her spirit. In one paragraph she mocked her own writing, “The thing now reads thin and pointless; the words scarcely dint the paper.” A few sentences later, she says, “I am about to write something good; something rich and deep and fluent …”

Every one of her works was meticulously drafted, rewritten, and revised in keeping with her perfectionist tendencies. “I assure you, all my novels were first-rate before they were written,” she wrote to her dear friend Vita Sackville-West in 1928. Crafting a narrative was exhilarating, but the process also left her drained and exhausted.

Similarly, when experiencing self-doubt or a writing slump, many of the other Literary Ladies I learned about let the inner critic urge them to do better. Think of your inner critic as a wise editor or an honest friend who won’t let you do less than the very best you can at the moment.

Excellent advice from such eminent writers. Thank you for the encouragement!

Thank you for your comment, Lisa — these women are so inspiring!

Great piece Nava, thanks for writing.

Thank you, Melanie.