Beyond the Legend: Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West’s Love Affair & Friendship

By Elodie Barnes | On May 9, 2020 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (5)

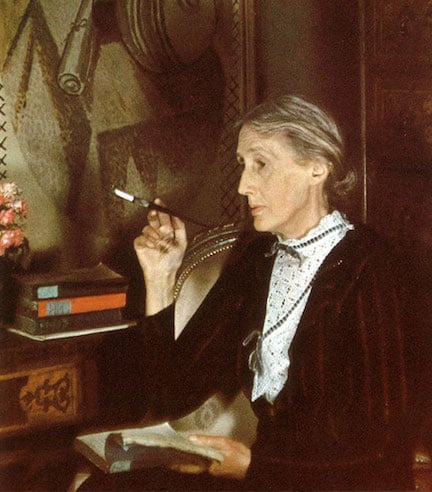

The relationship of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West has earned a place in literary history, and continues to fascinate with its allure of the unconventional, bohemian, and charmingly eccentric.

On December 15, 1922, Virginia Woolf recorded in her diary that she had met “the lovely aristocratic Sackville-West last night at Clive’s. Not much to my severer taste … all the supple ease of the aristocracy, but not the wit of the artist.”

She was, of course, writing of Vita, the woman who would go on to become her lover, friend, and confidante.

Their affair has inspired biographies, a West End play, and most recently, a 2019 film (the reception of the latter having been tepid). But none have come close to capturing the vibrant nuances and dynamics of their personalities, or the subtleties of a relationship that was more emotional than physical and that lasted until Virginia’s death in 1941.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf

. . . . . . . . . . .

A discouraging start

By the time she met Virginia, Vita was thirty years old and an established author, having published several volumes of poetry and fiction with more commercial than literary success.

Virginia was ten years older, and had published three novels and survived three major bouts of insanity. The age difference and the apparent emotional fragility did not deter Vita, however, whose first impressions were far more favorable than Virginia’s. Soon after their first meeting, she wrote to her husband Harold Nicholson:

“I simply adore Virginia Woolf, and so would you … Mrs Woolf is so simple…At first you think she is plain, then a sort of spiritual beauty imposes itself on you, and you find a fascination in watching her…I’ve rarely taken such a fancy to anyone”.

In true Vita style — slightly arrogant, slightly pushy, but with a charm and vitality that few could resist — she persuaded Virginia into several dinners (although not into membership of the P.E.N.Club, an international author’s society of which Vita was a member).

A flurried exchange of letters and books followed … and then nothing. Perhaps Vita was snubbed at Virginia’s refusal to join the P.E.N. Club, or more likely she was preoccupied with her new affair with architectural historian Geoffrey Scott.

Virginia, meanwhile, was working on both Mrs. Dalloway and The Common Reader. It wasn’t until late spring 1924 that correspondence between the two resumed and an intimacy, of sorts, was formed.

. . . . . . . . . .

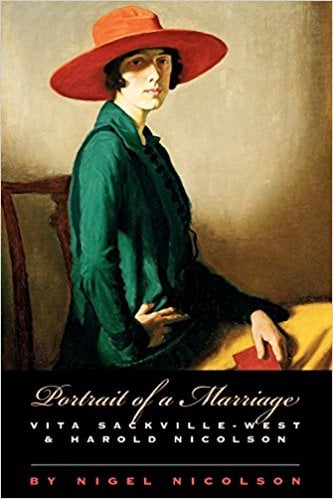

Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West & Harold Nicolson

. . . . . . . . . . .

Seduction in Bloomsbury

Despite her initial dismissal of Vita’s artistic merits, Virginia enjoyed both Vita’s poetry and fiction. In May 1924 she threw down a gauntlet: would Vita write a novel for the Hogarth Press (the small press she ran with her husband Leonard Woolf), and would she write it while on holiday in Italy that summer?

Vita responded by writing from Italy that she hoped “no one has ever yet, or ever will, throw down a glove I was not ready to pick up.” The result was Seducers In Ecuador, which she dedicated to Virginia.

Over the next few months, they settled into a tentative sparring back and forth, in language that became more and more flirtatious and intimate. Their letters show that a dichotomy of sorts was developing: Virginia saw Vita as the superior woman, while Vita saw Virginia as the superior writer.

Virginia’s response to Vita’s advances was a mix of guarded acquiescence and gentle mockery, and already Vita was playing not only the larger-than-life aristocrat (the “superior woman” that Virginia so admired) but also the protective maternal figure to Virginia’s sometimes helpless child.

Virginia, in turn, could also be Vita’s mistress of letters, appearing unattainable, unpredictable, and unapproachable; all aspects of her character that gave her a mysterious allure and simply added to Vita’s fascination.

But she was also affectionate and — perhaps more importantly — willing to indulge Vita’s aggressive side. When Vita accused her of using other people “for copy,” not thinking that Virginia would take offense, Virginia responded,

“I enjoyed your intimate letter…It gave me a great deal of pain – which is I’ve no doubt the first stage of intimacy…Never mind: I enjoyed your abuse very much.”

“I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia …”

In September 1925, Harold Nicholson was informed by the Foreign Office that he would be posted to the British Legation in Tehran, and it was arranged that Vita would join him in January and remain until May.

The news startled Virginia into realizing how much Vita had come to mean to her. Vita was “doomed to go to Persia; & I minded the thought so much (thinking to lose sight of her for 5 years) that I conclude I am genuinely fond of her…”

With the prospect of months of separation, Virginia visited Vita’s home at Long Barn in Kent that December. She stayed for three nights, and Vita made a note in her diary for the 17th: “A peaceful evening.”

For the 18th, though: “Talked to her til 3 am — Not a peaceful evening.” It’s generally agreed that it was during this time at Long Barn the two became lovers.

After this progression of their relationship, separation was all the more difficult. Vita was honest with Harold who, after suffering through the chaos of Vita’s affair with Violet Trefusis just a few years earlier, was understandably worried.

Vita sought to reassure him, saying that she would not fall in love with Virginia, nor would Virginia fall in love with her. Despite this, on the journey to Tehran Vita penned some of the most poignant love letters in literary history.

From Italy, she wrote “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia,” and from the Red Sea, “I find it very difficult to look at the coast of Sinai when I am also looking inward and finding the image of Virginia everywhere.”

But Vita never entirely lost herself: in amongst the letters are the traveller’s insights and the adventurer’s spirit that would eventually find expression in A Passenger to Teheran, also published by the Hogarth Press.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Signs of affection: “Potto” and “Donkey West”

When Vita returned from Tehran their relationship continued, but rarely in a sexual way. Vita was a passionate woman who often sought affairs outside of her marriage, but she had “too much real affection and respect” for Virginia to toy with her.

Mindful of the episodes of madness which had already left Virginia fragile, she initiated few sexual encounters. The love she felt for Virginia, she said, was not a sexual thing but “a mental thing; a spiritual thing, if you like, an intellectual thing, and she inspires and feeling of tenderness…”

Their letters during this time show a deepening of emotional intimacy along with a sense of fun, sometimes beginning in the traditional way of “Dearest Vita” or “My dearest Virginia”, but sometimes addressed to “Potto” (Virginia) and “Donkey West” (Vita).

They became close enough for uncomfortable observations to also occasionally be made. Virginia once wrote to Vita that, “there is something obscure…something that doesn’t vibrate in you…something reserved, muted … It’s in your writing too, by the bye. The thing I call central transparency — sometimes fails you there too.”

Vita knew Virginia was right, writing to Harold, “Damn the woman, she has put her finger on it … the thing which spoils me as a writer; destroys me as a poet.”

But emotional intimacy wasn’t enough. Vita was a fierce woman, with a longing for adventure that no amount of traveling to and from Tehran could satisfy. This time, the adventure presented itself in the form of Mary Campbell, wife of the poet Roy Campbell, and by October 1927 they were lovers.

Vita’s love letters to Virginia continued as if nothing was wrong, however Virginia sensed immediately that Vita’s attention had wandered.

. . . . . . . . . . .

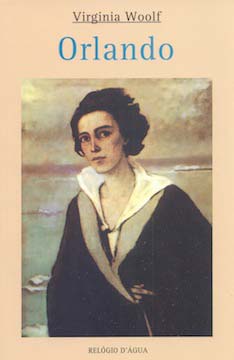

Orlando by Virginia Woolf: Gender and Sexuality Through Time

. . . . . . . . . . .

The longest love letter in literature

The unexpected result of Vita’s lapses in fidelity, drawn out over a period of several months, was one of the most personal “biographies” in literary history: the fictional account of Vita’s life that was Orlando.

On October 9, Virginia wrote to Vita that she was aware of Mary Campbell, and also to tell her about the idea for Orlando:

“Suppose Orlando turned out to be Vita; and it’s all about you and the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind (heart you have none, who go gallivanting down the lanes with Campbell)…Shall you mind? Say yes, or No.”

Vita readily agreed. as the writing flowed, Orlando became a version of Vita that, while completely recognizable to anyone who knew her, was also purely Virginia’s; a creation that could not be taken from her, who was safe beyond the lure of other women.

It also posed some interesting questions for Virginia as she withdrew, busy writing the fictional Orlando / Vita into existence while the real Vita was continuing to see Mary Campbell. She often wondered in her diary which was the more real.

In September 1928 the two women took a long-awaited holiday to France — the first and only holiday they would take together. Both were nervous about the prospect of close day-to-day proximity, but the week was a success. Further successes followed on their return with the publication of Orlando.

Reviewers loved it and Vita, who had not so far been allowed to read a word, found herself “enchanted, under a spell.”

Even Harold Nicholson praised it, writing to Virginia from Berlin, “It really is Vita — her puzzled concentration, her absent-minded tenderness … She strides magnificent and clumsy through 350 years.”

Their son Nigel would later refer to the book as “the longest and most charming love letter in literature.” Only Vita’s mother disliked it, writing to Virginia, “… probably you do not realise how cruel you have been.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sissinghurst Gardens

. . . . . . . . . . .

Sissinghurst

With Orlando, though, Vita felt as if Virginia truly had “found her out.” All aspects of her character, including those she usually kept hidden even from herself, had been laid bare. She felt as if there was nothing that could now be kept from Virginia.

As an artist and fellow writer, her admiration for Virginia increased, while emotionally she began to withdraw. Virginia once again sensed what was happening but knew that there was nothing she could do about Vita’s affairs.

Further change was precipitated by the resounding successes of Vita’s novels The Edwardians, published by the Hogarth Press in 1930, and All Passion Spent, published in 1931.

With the money that she earned Vita was able to purchase Sissinghurst Castle in Kent, the renovation of which would become her life’s project and the garden of which would make her more famous than her novels.

It also took her one step further away from Virginia, who split her time — along with Leonard — between London and Monk’s House in Sussex.

Although they saw each other from time to time and continued to exchange letters, the restoration of Sissinghurst took most of Vita’s attention while Virginia was enjoying a new friendship with the composer Ethel Smyth.

Her feelings for Vita remained unabated, but even she couldn’t close her eyes to the changes that were happening as Sissinghurst became the centre of Vita’s world.

The onset of war

With the approach of the Second World War, Virginia was becoming tense and fragile. Her nephew Julian Bell had been killed in the Spanish Civil War, and she had just finished her longest and most arduous (to write) novel, The Years.

It was against this background of bloody exhaustion that she wrote Three Guineas, a passionate denunciation of wars and the patriarchy which perpetuated them.

It was published in 1938 and caused one of the only serious quarrels she ever had with Vita, who alleged that the book contained “misleading arguments” that amounted to dishonesty.

Several stinging letters flew back and forth between London and Sissinghurst before Virginia was satisfied that Vita had not been accusing her of deliberate deceitfulness.

Behind all of this was the shadow of war, and their responses to it could not have been more different. Vita’s intrinsic aggressiveness was sparked to life — she came down from her pink Kentish tower, rolled up her sleeves and volunteered as a local ambulance driver.

Virginia, however, was horrified. War, to her, meant loss and deprivation. It meant no readers, and without readers there were no writers and no creativity. War also meant the end of personal independence as books struggled to sell and the Hogarth Press struggled to publish.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I might have saved her”

The women kept in touch through the first years of the war. Virginia occasionally visited Sissinghurst, when petrol rations and air raids allowed, and Vita kept the Woolfs supplied with butter and eggs.

But by 1941 Virginia had begun to drift into a strange state of serenity that quickly turned into the deepest of depressions. The strain of war, the fear of old age and of another period of insanity, and the terror of failing as a writer all converged to produce, for her, the perfect storm.

On March 28, 1941 Virginia ended her own life by drowning herself in the River Ouse.

Vita had had no idea of Virginia’s state of mind, and the shock would haunt her for years. Later, she wrote to Harold, “I still think that I might have saved her if only I had been there and had known the state of mind she was getting into.”

She could well have been right, but we will never know. It was the sad end of a long and passionate friendship that was far more vibrant in life than portrayed on screen, and one that will surely continue to fascinate for years to come.

Sources

All letter and diary quotes are taken from The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, edited by Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell Leaska, Cleis Press 1984, and from Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West by Victoria Glendinning, Penguin 1983.

Further reading

- The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, edited by Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell Leaska.

- Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West by Victoria Glendinning

- Virginia Woolf by Hermione Lee

- A Writer’s Diary by Virginia Woolf (edited by Leonard Woolf)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More literary friendships

- George Eliot & Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Lillian Hellman & Dorothy Parker

- Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings & Zora Neale Hurston

This review of Vita and Virginia (2019 film) is typical of the tepid response to the film

Although I have been a feminist from the 70’s till now, I have never read Virginia’s works.. I’m off to the library. I did see the movie Orlando and liked it, I feel I will love the book more!!

Thank you for this lovely piece. Had it not been for Portrait of a Marriage and Virginia Woolf, I would have walked into the Atlantic myself. Thank God for the truth of women’s friendships.

mj

Thank you for your kind feedback, MJ, and kudos to the author of this piece, Elodie Barnes.

Thank you! My beloved Virginia Woolf seems to have fallen out of fashion lately, and I am so grateful to have a well researched and enjoyable article to read about her!

Jean, thank you for your kind comment, and credit where due to Elodie Barnes for this fascinating article. I hadn’t realized that Virginia had fallen out of fashion in some way; is she studied less than she was in the last decade or two, I wonder? However, I do believe she’ll always be considered a classic, and a groundbreaker in literature as well.