8 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

By Nava Atlas | On February 8, 2022 | Updated February 15, 2024 | Comments (0)

In the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s, and the years just before and after, a notable number of Black women made a name for themselves as writers, playwrights, poets, editors, and journalists.

Here, we’ll take a look at seven Black women playwrights of the early twentieth century. For further in-depth overviews of Black women playwrights of the early twentieth century, consult these sources:

- Black Female Playwrights: An Anthology of Plays Before 1950 (Kathy A. Perkins, editor). Indiana University Press, 1990.

- “Angelina Weld Grimké, Mary T. Burrill, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and Marita O. Bonner: An Analysis of Their Plays” by Doris E. Abramson in Sage, 1985 (This article is excellent, though it requires access to academic libraries via ProQuest)

- A brief overview of women playwrights whose work rose to prominence during the Harlem Renaissance era can be found in chapter 1 of Their Place on the Stage: Black Women Playwrights in America by Elizabeth Brown-Guillory. Prager, 1988.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Marita O. Bonner

Marita Odette Bonner (1899 – 1971) was a short story writer, playwright, and essayist. Between 1925 and 1927 she produced a great number of short stories featuring characters from varied cultures navigating urban life.

Bonner was academically talented as well as a gifted pianist and composer. She was one of the earliest Black students at Radcliffe College. Jim Crow wasn’t just limited to the South, Bonner was forced to commute for all of her college years, as Black students weren’t allowed to live on campus. Upon her 1922, graduation, when she was named “Radcliffe’s Beethoven,” Bonner continued to bloom.

She became known for two prize-winning essays — “On Being Young—A Woman—and Colored” (1925) and “Drab Rambles” (1927). In the late 1920s, Bonner wrote three plays, the best known of which was The Purple Flower (1928). Her writing often dealt with the challenges facing Black communities in a racist society.

Marita Bonner continued to write short fiction until 1941, after which she focused on raising her three children as well as teaching high school in Chicago. Find Bonner’s plays in printed form:

The Pot-Maker (A Play to be Read): (Opportunity 5, Feb. 1927: pp. 43-46)

The Purple Flower.(The Crisis 35, Jan. 1928: pp. 202-07)

Exit — An Illusion.(Crisis 36, Oct. 1929: pp. 335-336; 352)

. . . . . . . . . .

Mary P. Burrill

Mary P. Burrill (1881 – 1946) was a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance era; her two plays, considered of cultural significance, were published in 1919. They That Sit in Darkness was published in Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review, and Aftermath, published in The Liberator, a socialist publication. Aftermath was staged in New York City in 1928 by the Krigwa Players.

Burrill’s theatrical writings were classified as protest plays, as they aimed to advance views on social issues, notably race and gender. Burrill remained a central figure in the Washington, D.C. wing of the Harlem Renaissance movement, where she hosted a literary salon to encourage writers and other creative artists of the movement. She also enjoyed a long career at Dunbar High School, where she taught English and drama and directed plays and musicals.

Burrill’s partner was Lucy Diggs Slowe, who was appointed Dean of Women at Howard University (one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in 1922. They were ahead of their time, living as a couple for twenty-five years, and even bought a house together. Burrill was heartbroken when Slowe died in 1937.

It’s not easy to find the full text of They That Sit in Darkness; the full text of Aftermath can be read here.

. . . . . . . . .

Alice Childress

Alice Childress’s first full-length play, Trouble in Mind, premiered in 1955 at an interracial theater co-sponsored by a Presbyterian church and a synagogue in Greenwich Village.

Childress (1916 – 1994) was very familiar with the challenges for Black actors. She was a co-founder of the American Negro Theatre and performed and directed with that company for a decade. She also worked in white-controlled venues, including on Broadway and for radio and television.

Often told she was “too light” for Black roles and “too Black” for other roles, she began writing herself because she wanted to create a wider range of opportunities for Black performers. She also felt some satisfaction in taking up a pen, noting that African Americans were the only racial group ever barred from literacy in the United States. Read more about Alice Childress and Trouble in Mind.

. . . . . . . . . .

Angelina Weld Grimké

Angelina Weld Grimké (1880 – 1958) was an American essayist, playwright, and poet whose work was frequently featured in The Crisis, the influential journal of the NAACP, and anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance era. She’s best remembered for her poetry and short stories. Themes of race and bias played a prominent role in her poetry and plays.

Rachel (which you can read in full by linking through) was the only play she wrote that was staged, but it was of great historic significance as one of the first public productions of a work by a woman of color. It had its debut in Washington D.C. in 1916 and was formally published in 1920. The program read:

“This is the first attempt to use the stage for race propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relative to the lamentable condition of the millions of Colored citizens in this free republic.”

Grimké wrote just one other play, Mara, which, like Rachel, dealt with the theme of lynching. It remains unpublished. Rachel was staged in a virtual performance by the Roundabout Theatre Company in 2021.

. . . . . . . . .

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 – 1960) had a dual career as a writer (producing novels, short stories, plays, and essays) and anthropologist.

Though Zora is better known today for her novels (particularly Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), short stories, and essays, she was a surprisingly prolific playwright. Zora’s plays are far less known than her fiction and nonfiction works, mainly because most remain unpublished and unproduced. Still, they reveal another aspect of her talent and ambition. Most of the following plays can be accessed at the Collection of Zora Neale Hurston Plays at the Library of Congress.

The first play, Meet the Mamma, is dated 1925; the last, Polk County, is from 1944. The rest are dated from 1930 to 1935:

Meet the Mamma: A Musical Play in Three Acts; Cold Keener, a Revue; De Turkey and de Law: A Comedy in Three Acts; Mule Bone: A Comedy of Negro Life in Three Acts (co-written with Langston Hughes); Forty Yards; Lawing and Jawing; Poker!; Woofing; Spunk; Color Struck; Polk County: A Comedy of Negro Life on a Sawmill Camp with Authentic Negro Music in Three Acts.

. . . . . . . . . .

Georgia Douglas Johnson

Georgia Douglas Johnson (1880 – 1966) was best known as a poet active during the Harlem Renaissance era, though she also was an avid musician, teacher, and anti-lynching activist. She was one of the first African-American female playwrights and produced four books of poetry.

It’s estimated that she wrote nearly thirty plays, some of which have been lost along with other portions of her work. Of those, there are some twelve surviving plays. Although none of Georgia’s plays were published in her lifetime, several were staged at community venues such as churches, schools, YMCAs, and such. By the time she delved into writing plays, she had already earned a solid reputation as a published poet with Heart of a Woman and Other Poems (1918) and Bronze (1922).

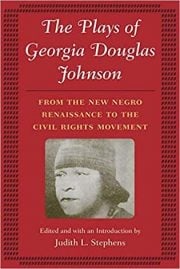

A comprehensive collection of her surviving plays was published in 2006 — The Plays of Georgia Douglas Johnson: From the New Negro Renaissance to the Civil Rights Movement. this is the best resource in which to read her plays in full. It contains: Blue Blood; Plumes; Frederick Douglass; Paupaulekejo; Starting Point; A Sunday Morning in the South (white church version); A Sunday Morning in the South (Black church version); Safe; Blue-Eyed Black Boy; And Yet They Paused.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

May Miller

May Miller (1899 – 1995) was one of the most widely published female playwrights and poets of the Harlem Renaissance era. Though poetry was her first love, her accomplishments branched out widely. She was the first African-American student to attend Johns Hopkins University and became one of the pioneers in the field of sociology.

Miller augmented her work as a writer with a distinguished career as a teacher and lecturer in several prestigious institutions. Her major plays addressed colorism within the Black community, Black servicemen, lynching, and other issues of race and class.

Her major works include: The Bog Guide (1925); Scratches (1929); Stragglers in the Dust (1930); Nails and Thorns (1933). These were all republished by Alexander Street Press from 2001 to 2003. In addition, Miller also wrote many historical plays, four of which (including Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth) were included in the anthology Negro History in Thirteen Plays (1935).

. . . . . . . . . . .

Eulalie Spence

Eulalie Spence (1894 – 1981) was so popular and prolific in her heyday that it’s hard to fathom her decline into obscurity. Like many of her contemporaries who bloomed during the Harlem Renaissance, she was multitalented—a writer and playwright as well as an actress and teacher. She authored some fourteen plays, of which five were published.

Spence, an immigrant from the British West Indies, believed that plays were meant to be fun and entertaining. Though this went against the prevailing notion that the purpose of all art was to agitate for social justice, she was a highly visible member of the Black theater community of the Harlem Renaissance, and one of its most popular.

Later, Spence became an important mentor to renowned theatrical producer Joseph Papp, who founded The Public Theater and the Shakespeare in the park theater festival in New York City. They encountered one another when she was the only Black teacher in his predominantly white high school; he described her as “the most influential force” in his life.

Spence’s plays were mainly produced in 1923 to 1929, except for The Whipping, which is dated 1934: The Starter; On Being Forty; Foreign Mail; Fool’s Errand; Her; Hot Stuff; The Hunch; Undertow; Episode; La Divina Pastora; The Whipping.

. . . . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT

Renaissance Women: 13 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read

Leave a Reply