Georgia Douglas Johnson, Harlem Renaissance Poet & Playwright

By Nava Atlas | On March 29, 2018 | Updated June 13, 2025 | Comments (0)

Georgia Douglas Johnson (September 10, 1880 – May 14, 1966) was an American poet and playwright associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Born Georgia Douglas Camp in Atlanta, Georgia, she grew up in a mixed-race family with African American, Native American, and English roots.

Her poetry addressed issues of race as well as intensely personal yet ultimately universal themes including love, motherhood, and being a woman in a male-dominated world.

Four collections of her poetry were published: The Heart of a Woman (1918), Bronze (1922), An Autumn Love Cycle (1928), and Share My World (1962). She wrote nearly thirty plays and numerous other works, some of which have been lost.

Georgia Douglas Johnson biography highlights

- Though Georgia lived in Washington D.C. for most of her adult life, she was considered an important member of the Harlem Renaissance movement. Her home became a meeting place and salon for New York’s literati visiting the capital city.

- Jessie Redmon Fauset, one of the Harlem Renaissance movement’s “literary midwives,” mentored Georgia and helped edit her first collection of published poems, The Heart of a Woman (1918).

- Georgia’s husband died in 1925, leaving her to raise and support their teenage sons. She worked as a file clerk for Civil Service and as a substitute teacher, but managed to keep writing.

- Sustaining a literary career was challenging in the 1930s and 1940s as she ushered her sons through law and medical school. In turn, they were later quite supportive of her.

- Georgia is a key figure in the genre of early African American theater, some twelve plays have been preserved, while quite a few more may have been lost.

- After a long gap, her final collection was published in the early 1960s. Unfortunately, many of her papers and writings were destroyed, but her work remains respected and influential as a part of the Harlem Renaissance period.

Settling in Washington, D.C.

Georgia graduated from Atlanta University’s Normal College 1893, then studied music at Oberlin Conservatory and the Cleveland College of Music. Her first line of work was as a teacher and an assistant principal in Atlanta.

After her marriage to Henry Lincoln Johnson, an attorney and government worker, the couple had two sons, and moved to Washington, D.C., in 1910. He wanted her to be a traditional wife and mother, caring for their home and two sons. Despite the lack of enthusiastic support from her husband, Georgia managed to find a way to write.

First publications: The Heart of a Woman and Bronze

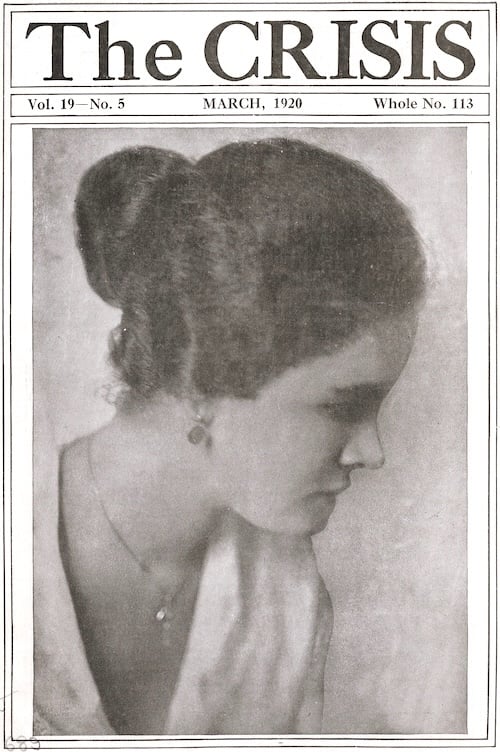

Georgia was in her mid-thirties when she first had her poems published in the NAACP’s Crisis magazine in 1916. Her first book of poetry, The Heart of a Woman, was published in 1918. Jessie Redmon Fauset, who was poised to become the literary editor of The Crisis, helped select the poems for the book.

The Heart of a Woman featured poems that were personal to her life, yet universal to the female experience. They spoke of love, loneliness, and life’s disappointments. In graceful terms, her frustration with women’s constrained roles was expressed as well. The title of this book was the inspiration for Maya Angelou’s 1981 memoir of the same name.

Bronze, Georgia’s second collection of poetry was published in 1922. In this volume, the poems more directly confronted themes of race. Now that she had established a name for herself, the book got wider coverage. Here’s a review that appeared in the Washington, DC Evening Star in January of 1923:

“Of this book of verse, W.E.B. Du Bois says in the introduction: ‘Those who know what it means to be a colored woman in 1922 — and know it not so much in fact as in feeling, apprehension, unrest — must read Bronze. None can fail to be caught here and there by a word, a phrase, a period that tells a life history, or even paints the history of a generation … the book is singularly sincere and true, a revelation of the soul struggle of the women of a race — and invaluable in this respect.’

The book itself lives up to the substance of this appreciation. Serious throughout, uplifting at times, rarely bitter, deeply sorrowful, Bronze is an unmistakable cry of the human who is still in bondage. Not physical bondage, true, but bondage of teh spirit in many manifestations.

As poetry, the claim of this book can’t be justly denied. It is good poetry, both in the letter of poetic laws and in the spirit of poetic feeling.”

A literary salon in the nation’s capital

Though Georgia was never a resident of New York City, which the heart of the Harlem Renaissance, her Washington home became an important literary salon. She became a welcoming host to her fellow writers.

Among the regular visitors were Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Alain Locke, and many of the noted women writers of the Harlem Renaissance. It was considered one of the great literary salons of the era, removed as it was from its geographic center.

The house at 1461 S Street NW came to be known as the “S Street Salon” — a satellite of sorts for writers in the nation’s segregated capital. Georgia called the home “Half-Way House” and provided not only a welcoming haven for visitors, but shelter for artists in need.

. . . . . . . . . . .

13 Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

. . . . . . . . . . .

The 1920s: A productive decade

When Georgia’s husband died in 1925, she was forty-five years old and had to find a way to support their teenage sons. She worked at temporary jobs, including as a file clerk for Civil Service and as a substitute teacher. Though she was finally hired by the Department of Labor, she worked long hours for low pay.

Despite these obstacles, the twenties were a busy and productive period. She wrote a weekly syndicated column that appeared in a number of Black newspapers including New York Age and Pittsburgh Courier. Called “Homely Philosophy,” it ran from 1926 to 1932 and dispensed brief tidbits of wisdom like this one from 1933:

“Do not be easily wounded, it is a sign of smallness. Great souls pass lightly over trifles and make allowances for the small defects in the actions of other. Little minds are too much wounded by little things. Be big minded!”

In the same period, she wrote a number of plays, including Blue Blood, which was staged in 1926 and Plumes (1927). She also traveled far and wide in the twenties, doing readings and giving lectures.

An Autumn Love Cycle (1928) returned to the more personal themes explored in The Heart of a Woman. This collection included “I Want to Die While You Love Me,” perhaps her best-known and most widely reprinted poem. An Autumn Love Cycle is generally Georgia Douglas Johnson’s most widely praised collection.

Never giving up the creative fire, despite challenges

Georgia lost her job at the Department of Labor job in 1934. She returned to doing temporary clerical jobs and whatever other work she could find. Through her hard work and determination, she sent her sons through college.

Henry Johnson Jr. went to Bowdoin College and Howard University Law School. Peter Johnson attended Dartmouth college, and completed his medical degree at Howard University.

Maintaining her literary career while having to survive financially and send her sons through college was difficult. In the 1940s and 50s, Georgia sporadically published poems and appeared on radio programs, but it wouldn’t be until the early 1960s that her next collection would be published.

Though she often lacked material support, Georgia never gave up on the creative fire that was inside her soul nor her commitment to encouraging other artists in their endeavors.

A review in the San Francisco Examiner of Color, Sex, and Poetry: Three Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance by Gloria T. Hull (Indiana University Press, 1988) observed:

“Johnson was plagued by the female artist’s traditional conflict: housework versus writing time, duty versus self-expression. Her huge output in the face of such problems is staggering, and Hull looks carefully at her plays, short stories, and lovely, economical verse:

How much living have you done?

From it the patterns that you weave

Are imagined.

Still, her portrait of Johnson — a complex woman whose apparently romantic poems were edged with irony — remains rather unfocused, a casualty, perhaps, of having such wide-ranging material to work with.”

. . . . . . . . .

Georgia Douglas Johnson as playwright

Although none of Georgia’s plays were published in her lifetime, several were staged at community venues such as churches, schools, YMCAs, and such. By the time she delved into writing plays, she had already earned a solid reputation as a published poet with Heart of a Woman and Other Poems (1918) and Bronze (1922).

A comprehensive collection of her surviving plays was published in 2006: The Plays of Georgia Douglas Johnson: From the New Negro Renaissance to the Civil Rights Movement. Judith L. Stephens, the editor of the collection, wrote in her Introduction:

“Johnson is a key figure in theatre history and her plays are landmark contributions to both African American theatre and American theatre in general. She wrote for community-based non-profit venues that offered alternative to predominantly white, male, and New York City-centered theatre; she was a pioneer in the national movement known as the New Negro theatre of the 1920s and 1930s; and she is the most prolific playwright in the American “lynching drama tradition.”

Those interested in a deep dive into Georgia Douglas Johnson’s plays and their place in American theatre history would do well to seek out this book, published by the University of Illinois Press.

Later years, the loss of important work

Later in her life, Georgia moved in with Henry Lincoln, Jr. and his wife. Her last collection of poetry was published in 1962. Share My World reflected her life experience and wisdom. Despite the challenges she faced, Georgia continued to be generous to fellow artists, and an enthusiast of all things literary and artistic.

In 1962 – 63, Georgia compiled a “Catalogue of Writings.” She listed twenty-eight plays, though only a few have been preserved. She also listed a manuscript about her literary salon and a novel, both of which have also been lost. Of thirty-one short stories she listed, only three have been found. Her personal papers are gone.

All of these published and unpublished works might have been thrown away by mistake while clearing out her belongings after her death. It’s tragic to think that the prolific output of this talented and determined writer will never be recovered. There are hardly any surviving photos of her, either.

Georgia Douglas Johnson received an honorary doctorate in literature from Atlanta University in 1965. She remained active into her eighties and died of a sudden stroke in 1966.

Contemporary analysis of Georgia Douglas Johnson’s work

Ann Allen Shockley, in Afro-American Women Writers 1746 – 1933, observed that among the circle of female poets of the Harlem Renaissance, Georgia Douglas Johnson was the most popular:

“She published her poems in book form, which brought her more public attention. She is often belittled for her poems of the heart, which her white contemporary and friend, Sara Teasdale, wrote also. Pulitzer Prize winner Teasdale was more successful, however, for she had an appreciative audience.”

Though Georgia’s surviving body of work isn’t large, it continues to be well regarded. In The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States (1995), Eugenia Collier wrote:

“Georgia Douglas Johnson’s poems are skillfully crafted lyrics cast in traditional forms. They are, for the most part, gentle and delicate, using soft consonants and long, low vowels.

Their realm is emotion, often sadness and disappointment, but sometimes fulfillment, strength, and spiritual triumph. Yet Johnson herself was never otherworldly. She remained in the forefront of political and social events of her time.

Her plays were moving portrayals of the tragic impact of racism upon African Americans. Frequent themes in both her poetry and drama are the alienation and dilemmas of the person of mixed blood and the goal of integration into the American mainstream.”

And finally, Melanie Lawrence, in a 1988 review of Color, Sex, and Poetry: Three Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance by Gloria T. Hull, wrote:

“Johnson was plagued by the female artist’s traditional conflict: housework versus writing time, duty versus self-expression. Her huge output in the face of such problems is staggering, and Hull looks carefully at her plays, short stories, and lovely, economic verse.”

More about Georgia Douglas Johnson

On this site

- 10 Poems by Georgia Douglas Johnson

- The Heart of a Woman (1918) – full text

- Bronze: A Book of Verse (1922) – full text

- An Autumn Love Cycle (1928) – full text

Poetry Collections

- The Heart of a Woman (1918)

- Bronze (1922)

- An Autumn Love Cycle (1928)

- Share My World (1962)

Plays

The Plays of Georgia Douglas Johnson, edited by Judith L. Stephens (2006), which contains:

Blue Blood

Plumes

Frederick Douglass

Paupaulekejo

Starting Point

A Sunday Morning in the South (white church version)

A Sunday Morning in the South (Black church version)

Safe

Blue-Eyed Black Boy

And Yet They Paused

More information and sources

- Poetry Foundation

- Georgia Douglas Johnson’s Life and Career

- Georgia Douglas Johnson: Harlem Renaissance Writer

- All Poetry: Georgia Douglas Johnson

- Goodreads

Leave a Reply