Eulalie Spence, Playwright of the Harlem Renaissance Era

By Nava Atlas | On August 7, 2022 | Updated February 15, 2024 | Comments (4)

Eulalie Spence (June 11, 1894 – March 7, 1981) was an award-winning American playwright, stage director, actress, and educator. As a prolific Black writer in the first half of the twentieth century, Spence was most active during the Harlem Renaissance era.

She was so esteemed and prolific in her heyday that her relative obscurity today is unfathomable. Like many of her contemporaries who blossomed during the Harlem Renaissance years, she was multitalented — a writer and playwright, as well as an actress and teacher. She authored some fourteen plays, five of which were preserved in print; nearly all were staged.

An immigrant from the British West Indies, Spence went against the prevailing trend of her time among Black creatives, which was to use the arts in all forms to press for racial justice. She believed that plays were for entertainment and considered herself a “folk dramatist.”

She was a member of W.E.B. Du Bois’s Krigwa players from 1926 to 1928, and though she clashed with the eminent Du Bois about the purpose of theatre, she was a highly visible member of the Black arts community of the Harlem Renaissance, and one of its most popular.

Later, Spence became a mentor to one of her high school students who would later become a renowned theatrical producer. That was none other than Joseph Papp, founder of The Public Theater and Shakespeare in the Park theatre festival. Spence was the only Black teacher in his predominantly white high school, and he described her as “the most influential force” in his life.

As a playwright, Spence was most active from 1923 to 1929; her last and most controversial play, The Whipping, came out in 1934.

Early years—from the British West Indies to Brooklyn

Eulalie Spence was born in Nevis, British West Indies, to Robert and Eno Lake Spence. Her early childhood was spent on her father’s sugar cane plantation. When it was destroyed by a hurricane in 1902, the family moved to New York City. They briefly lived in Harlem before settling in Brooklyn.

Eulalie’s upbringing in a family of seven girls wasn’t easy under the family’s circumstances. Still, she maintained a gentle, loving spirit that helped keep the large family close-knit. Robert struggled to keep steady work, always dreaming of returning to his homeland. The family endured a hardscrabble life in a tiny Brooklyn apartment.

Despite the impoverished circumstances of her childhood in Brooklyn, Spence managed to draw positive inspiration from her parents. Her mother would often read to her, which strengthened their bond. She admired her mother’s strong and independent demeanor. These attributes would later inspire the female characters in her plays.

. . . . . . . . . . .

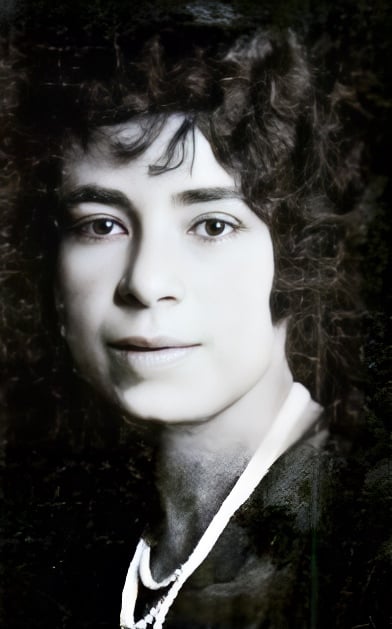

Eulalie Spence in the 1920s

. . . . . . . . . . .

Education and teaching career

Eulalie forged a path through school to get a good education. She graduated from the Wadleigh High School for Girls, which became the first all-girls’ public high school in New York City.

After Wadleigh, Eulalie attended and graduated from the New York Training School for Teachers. In 1924, she enrolled at National Ethiopian Art Theatre School, whose primary aim was to empower Black actors through training and employment.

Much later, she continued her education, culminating – with a Master of Arts in Speech from Teacher’s College, Columbia University in 1937.

She taught at the Eastern District High School in Brooklyn for more than thirty years, from 1927 to 1958, overlapping with her theatrical endeavors (she didn’t make a living from the latter). The only Black teacher in a predominantly white school, she taught dramatics, English, and elocution. As mentioned earlier, one of her students was Joseph Papp, who was greatly inspired by her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT

Renaissance Women: 13 Female Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance to Rediscover and Read7 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

. . . . . . . . . .

Playwriting, acting, and directing career

Though she authored some fourteen plays, Spence’s creative journey wasn’t an easy one. Her star as a playwright shone brightest in the 1920s, in the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance era.

Most of Spence’s plays were performed by a theatre company known as Krigwa (Crisis Guild of Writers and Artists). She first affiliated with them when she won second place in the group’s 1926 playwriting competition. Her one-act play was titled Foreign Mail.

Krigwa (formerly known as Crigwa), was founded in 1925 by William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois. It started with the mission of sponsoring an annual playwriting competition, and later transitioned into a theatre company for staging plays.

The primary aim of the Harlem-based theatre group was to create, nurture, develop, and promote budding writers, performers, actors, and directors housed in the black community.

That same year, a second play titled Her saw her win yet another second-place award in a literary contest hosted by Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. Her received countless accolades for its skillful writing.

Her ushered in the second season of the Krigwa Players which had Spence’s two sisters, Olga and Doralene, take part in the productions. Later in 1927, another of Spence’s plays, The Hunch, came in second in yet another round of the Opportunity contests; Undertow tied for third place in a 1927 contest sponsored by The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP.

Fool’s Errand (1927) was a finalist in the International Little Tournament on behalf of the Krigwa Players; it was subsequently published by Samuel French.

In addition to these award-winning works, Spence wrote several other plays. On Being Forty is one of her best-known plays; it was staged on several occasions, including a production by the Bank Street Players and the National Ethiopian Art Theatre.

Spence had the privilege of directing two plays around this period for the Dunbar Garden Players. These were Joint Owners in Spain by Alice Brown and Before Breakfast by Eugene O’Neill.

Spence preferred to write comedies and drama and would avoid racial propaganda as much as possible. Her plays would often focus on the day-to-day domestic lives of African-Americans especially touching on typical love triangles where male characters tended to be weaker than female characters.

While her characters were typically Black, she preferred to steer clear of racial themes. What’s more, she made use of Black dialect, which often subjected her to criticism by some of her contemporaries in the Black arts community.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A major career fallout

While Eulalie Spence was doing well as a playwright under the umbrella of Krigwa Players, she eventually experienced a career setback. Though she helped expand the visibility of this theatre group, Spence never saw eye to eye with W.E.B. Du Bois.

Du Bois insisted that theatre and other arts were for the purpose of positive propaganda, to elevate the stature of Black people. Spence felt that theatre was better leveraged as a vehicle for entertainment. She emphasized her stance in a widely read essay for Opportunity magazine. In it, she wrote: “We go to the theatre for entertainment, not to have old fires and hates rekindled.”

Since she refused to write the kind of dramas Du Bois thought she should, they came to a major fallout. In the 1927 Little Theatre Tournament, Du Bois decided to keep all the prize money to himself at the expense of paying Spence and other actors. This resulted in the disbandment of the Krigwa Players.

The Whipping — a controversial final play

In 1934, Eulalie Spence adapted The Whipping, a novel by Ron Flanagan. It would be her last play as well as her only three-act play, marking a significant milestone in her writing career.

The Whipping features a sensational plot that goes beyond the Black/white racial divide in a rather spectacular articulation. Spence went past the norm of that era and instead of writing about the lives of black people which most Black female writers in the Harlem Renaissance were accustomed to, she wrote about the theatrics of a white woman. It involved this character subverting the Klan.

Further fueling controversy around The Whipping, it was not only adapted from a story by a white author about a white character, Spence hired a white agent to represent her, further breaking the prevalent racial barriers at the time.

Nonetheless, despite a buildup to a striking performance, Spence suffered another setback. Her scheduled production was abruptly canceled without notice or explanation just a few days before it was to open.

As a result, a devastated Spence was forced to option her screenplay to Paramount Pictures. She did receive five thousand dollars, a significant sum at the height of the Depression, but it was never adapted to film, nor staged. And it was the only money she ever earned for her writing. Despite these setbacks, The Whipping remains a significant milestone in Spence’s writing career.

After all the drama surrounding The Whipping, Spence withdrew from the public limelight and focused her attention on teaching at Eastern District High School. She continued to write and act for Columbia University’s Laboratory Players.

The Legacy of Eulalie Spence

Spence remains one of the most influential and prolific African-American female writers of the Harlem Renaissance era. In the eleven years of her most active writing phase, she successfully authored enduring masterpieces, from The Starter (1923) to The Whipping (1934).

In addition to her plays, Spence wrote noteworthy essays for Opportunity including “Negro Art Players in Harlem” and “A Criticism of the Negro Drama as it Relates to the Negro Dramatist and Artist” (both published in 1928).

Spence’s plays showed sensitivity to race and gender, drawing their emotional tenor from her family’s experiences as immigrants. She stood firm in writing what she called “folk plays,” which emphasized the daily lives of Black people, resisting Du Bois’s call for “race plays.” Her plays showcased strong female characters and sometimes featured love triangles.

Spence died at the age of eighty-six in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. At the time of her death, she had been living with her niece, Patricia Hart. Her obituary described her only as a retired schoolteacher, neglecting to mention her career as a significant playwright.

More about Eulalie Spence

Major Works (plays)

- The Starter (1923)

- On Being Forty (1924)

- Foreign Mail (1926)

- Fool’s Errand (1927)

- Her (1927)

- Hot Stuff (1927)

- The Hunch (1927)

- Undertow (1927)

- Episode (1928)

- La Divina Pastora (1929)

- The Whipping (1934)

More information and sources

- Wikipedia

- Eulalie Spence Papers — New York Public Library

- Lost Voices in Black History

- Talking B(l)ack: Construction of Gender and Race in the Plays of Eulalie Spence

I am a researcher and free-lance writer working on my 6th published book on theatre and politics. I am interested in using the wonderful “Head shot” image you have on this site of Eulalie Spence. I have seen it several places no one seems to be able to tell me the original source of this image so I can get permission to use it. Where did you find it. Who owns it? where is it archived?

Can you confirm it is public domain?

Looking forward to your response.

Joel Eis

Hello Joel — the origin of this head shot is: Uploaded a work by {{Unknown|author}} from [https://books.google.com/books?id=3W7XAAAAMAAJ&pg=RA2-PA270&lpg=RA2-PA270 ‘”Krigwa Prize Winners 1927″] ‘The Crisis” (January 1928 — so it is in the public domain. The original photo of Eulalie Spence that’s floating around is of such poor quality that we enhanced it on our end, to do justice to this talented and beautiful woman. You have my permission to use this enhanced version.

Thank you for this presentation of a great life , in remembrance of Eulalie Spence and Her story. I found reference to your article via mention of a friend in Trinidad & Tobago and their page on the internet.

Thank you, Mizan — Eulalie Spence led a creative life that has sadly been all too forgotten.