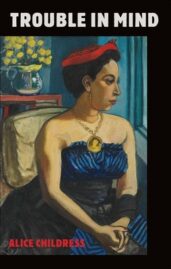

Trouble in Mind by Alice Childress – Playwright, Novelist & Activist

By Lynne Weiss | On February 15, 2024 | Updated April 5, 2024 | Comments (0)

The first full-length play by Alice Childress, Trouble in Mind, premiered in 1955 at an interracial theater co-sponsored by a Presbyterian church and a synagogue in Greenwich Village.

According to accounts at the time, the audience “applauded and shouted bravos, and would not leave their seats until the author was brought on stage.” Despite initial audience enthusiasm, decades would pass before the play received the recognition it has today as a classic of American theater.

The show received an Obie Award for best original off-Broadway play that season and was slated to open on Broadway in 1957, but Childress herself pulled the plug on that production.

Childress said she spent two years rewriting the play, especially the ending, to satisfy the would-be producers with a “heart-warming little story.” But in the end, Childress found she could not write a version that pleased her backers and that also met her own demands.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Alice Childress

. . . . . . . . . .

A Portrayal of White-Dominated Theater

Childress’s struggles with Trouble mirror the play itself. Set backstage, it presents the behind-the-scenes banter and rehearsals of the cast and crew as they prepare to perform a play called Chaos in Belleville, meant to be an anti-lynching play.

Childress was very familiar with the challenges for Black actors. She was a co-founder of the American Negro Theatre and performed and directed with that company for a decade. She also worked in white-controlled venues, including on Broadway and for radio and television.

Often told she was “too light” for Black roles and “too Black” for other roles, she began writing herself because she wanted to create a wider range of opportunities for Black performers. She also felt some satisfaction in taking up a pen, noting that African Americans were the only racial group ever barred from literacy in the United States.

Enter Wiletta, Our Hero

The central figure in Trouble is Wiletta, a middle-aged Black woman who has a starring role for the first time in her long career. Previously, she has played “character parts,” or stereotypes—“mammy” roles, mothers talking their sons out of demanding equality, wives of men who keep them “laughin’ all the time” despite their refusal to work or come home at night.

“You ever hear of a lazy, no-good, two-timin’ man keepin’ a woman laughin’ all the time?” Wiletta asks Al Manners, the white director of the play.

Manners sees himself as a liberal. He believes he should be congratulated for being willing to work with Black performers on a show that is critical of lynching, though the play was written by a white man who distorts the attitudes of those involved. Manners tries to elicit a stronger performance from Wiletta, claiming he wants “truth.”

“Truth,” he explains, “is simply whatever you can bring yourself to believe.”

Yet Wiletta finds herself unable to inhabit her role as a mother who urges her adult son, who has committed the “crime” of voting, to turn himself in to the authorities who promise to keep him safe from a lynch mob by putting him in jail. She knows what the outcome will be. “I don’t see why the boy couldn’t get away… something’s wrong,” she objects.

Manners dismisses her concerns, telling her that they don’t “want to antagonize the audience.” “It’ll make ‘em mad if he gets away?” Wiletta asks.

Manners asks Sheldon, an elderly Black actor who is desperate for work as he faces housing insecurity, whether he finds the script offensive. Sheldon assures Manners that the script is fine, but then he goes on to describe a lynching he witnessed as a child in Virginia. Manners responds that such accounts make him feel “wretched, so guilty.”

Wiletta seizes the opportunity to suggest changes in the script. Rather than passively urging her son to turn himself in, she wants to say, “Run for it!” pointing out that she would rather he died while seeking his freedom rather than walking to his own destruction.

Manners rejects her suggestions. Her objections become more heated, and the rest of the cast—both Black and white—begin to fear for their own jobs.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Broadway and Revivals

Trouble in Mind ends with no clue as to whether “Chaos in Belleville” will go forward or not. We do know that nearly twenty-five years would pass before Trouble in Mind had another significant production, this time by the New Federal Theatre Project in 1979.

Further productions followed, but at a slow pace. There was a London premier in 1992, and then New York’s Negro Ensemble Company mounted a production in 1998.

While the play contains references to events of the 1950s—the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Little Rock school desegregation riots—it has only been in the 21st century that its importance has been recognized by the mainstream theatrical world. Yale Repertory Theater produced it in 2007 and 2019; the Arena Stage produced it in Washington, D.C. in 2011.

After a 2010 production in San Francisco, there were numerous productions in Chicago, Seattle, Ontario, North Carolina, and New Jersey. The play’s long-delayed Broadway premiere in was in 2021.

That production was nominated for four Tonys, including Best Revival, Best Actress (LaChanze as Wiletta), Best Featured Actor (Chuck Cooper as Sheldon), and Best Costume Design. Since then, there have been further opportunities to see this work, including in London, Chicago, Winnipeg, Hartford, and Boston.

. . . . . . . . . .

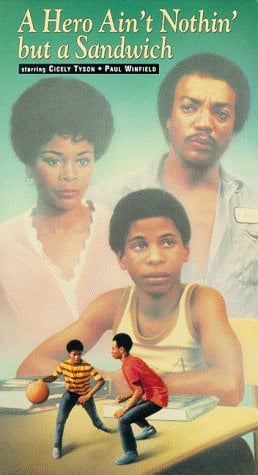

A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich

is one of Alice Childress’s best-known works

. . . . . . . . . .

A Realistic Ending

The version of Trouble in Mind generally mounted today offers an ending that is far from happy—yet not without hope.

According to Judith E. Barlow, in her introduction to Plays by American Women, 1930–1960, Childress’s ending implies “a bond among all oppressed peoples,” as Wiletta finds a sympathetic, though relatively powerless, ally in Henry, the elderly and overlooked Irish doorman, after everyone else in the cast and crew has abandoned her.

Present-day renditions of Trouble in Mind are hailed for their timeliness. Yet, according to Katy Perkins, who knew Childress well and edited an anthology of her plays, Childress “hated the saying ‘ahead of your time.’ Her thing was that people aren’t ahead of their time; they’re just choked during their time, they’re not allowed to do what they should be doing.”

Ahead of her time or not, Childress, who lived into the late 20th century (1916–1994), went on to write numerous plays and novels, most famously, A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ but a Sandwich (1973). She did not live long enough to see this renewed interest in her theatrical work, but one suspects it wouldn’t have mattered to her.

Like her character Wiletta, Childress looked into herself to find her truth. And then she said what she wanted to say when she wanted to say it. That it has taken the rest of the world decades to listen was not her concern. Time has vindicated the realism of her play and the truth of her message.

Sources:

- Barlow, Judith E. Plays by American Women 1930-1960. Applause Theatre Books, 2001

- Green, Jesse. “Review: ‘Trouble in Mind,’ 66 Years Late and Still On Time,” The New York Times, 18 Nov. 2021

- Phillips, Maya. “Alice Childress Finally Gets to Make ‘Trouble’ on Broadway,” The New York Times, 3 Nov. 2021

- Rule, Sheila. “Alice Childress, 77, a Novelist; Drew Themes From Black Life,” The New York Times, 19 Aug. 1994

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

You may also enjoy: 8 Black Women Playwrights of the Early 20th Century

Leave a Reply