The Literary Friendship of George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe

By Emily Midorikawa | On June 26, 2017 | Updated September 3, 2024 | Comments (0)

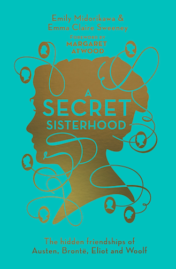

This musing on the literary friendship of British author George Eliot and her American contemporary Harriet Beecher Stowe is contributed by Emily Midorikawa, author of A Secret Sisterhood:The Hidden Friendships of Austen, Brontë, Eliot and Woolf.

Even before she found literary fame, Mary Ann Evans (1819 – 1880), better known by the pen name George Eliot, was firmly entrenched in a London social circle that was unconventional, intellectual, and predominantly male.

There was also the matter of her “living in sin” with critic and philosopher George Henry Lewes – a state that kept many “respectable ladies” away from her door.

When Elizabeth Gaskell, for instance, wrote to Eliot to praise her fiction, she couldn’t help lamenting that “I wish you were Mrs Lewes,” and didn’t pursue a closer relationship.

Other women, though, were undeterred, including the American author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe. Having previously received a kind message from Eliot (passed along on by a mutual friend), the fifty-seven-year-old Stowe first wrote to Eliot in the spring of 1869.

. . . . . . . . . .

George Eliot

. . . . . . . . . .

Stowe refers to Eliot as “My dear friend”

In a remarkably candid initial letter, Stowe greeted her recipient as ‘my dear friend’, then quickly moved from opening pleasantries to praise but also criticisms of Eliot’s books, which she had recently re-read ‘carefully pencil in hand’. She said, for instance, that the best aspects of Eliot’s shorter stories had not yet been fully achieved in her longer works.

Perhaps surprisingly, given Eliot’s well-known reserve, her response was enthusiastic. She warmed to Stowe’s ebullient personality, and, rather than being offended by her correspondent’s bolder suggestions, Eliot would reply that Stowe’s words had in fact assured her that her own work had been ‘worth doing’.

This transatlantic exchange marked the start of an important epistolary friendship that would continue until Eliot’s death.

. . . . . . . . . .

Harriet Beecher Stowe

. . . . . . . . . .

Markedly different personalities

At first glance, it may not seem obvious why the two women felt drawn together. They must have quickly realised that they would never have an opportunity to meet. Although in her first letter, Stowe had implored Eliot to visit America, personal circumstances and the ill health of Eliot’s partner and Stowe’s husband would mean that neither felt able to travel far from home.

Their personalities were markedly different too, as were their views on religion. Stowe was a staunch Christian, whereas Eliot had stopped attending church as a young woman when her critical reading had convinced her to abandon her earlier evangelical fervor.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A friendship based on common bonds

What seems to have cemented the relationship is a willingness to concentrate on areas in which their lives did converge: their shared status as legendary female authors, their ‘marriages’ to similarly scholarly men, and, of course, their interest in literature.

Communicating long-distance naturally meant enforced pauses in conversation, but these could have their benefits. The pair’s physical separation made it easier than if they’d lived in the same country for Stowe to regard Lewes and Eliot simply as husband and wife.

Likewise, it allowed Eliot to skirt away from trickier subjects, such as an essay of which she strongly disapproved in which Stowe alleged incest between the poet Lord Byron and his half-sister, as well as, at times, Stowe’s outpourings about her interest in spiritualism.

The ghost of Charlotte Brontë proves too much

However, the apparent revelation that Stowe had managed to make contact with the ghost of Charlotte Brontё seems to have proved too much for the rational Eliot. On this occasion, she was firmer than usual. ‘Whether rightly or not’, Eliot insisted, the account struck her as ‘enormously improbable’.

Over the course of their eleven-year bond, significant gaps occasionally occurred in their correspondence. But in each case Stowe and Eliot picked up the conversation again with relative ease – a testament to the power of this little-known friendship between two nineteenth century literary giants.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney, authors of A Secret Sisterhood: The Hidden Friendships of Austen, Brontë, Eliot and Woolf, published by Aurum Press in the UK and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in the U.S. (2017). Visit the authors on the web at Something Rhymed: Celebrating Female Literary Friendship.

About A Secret Sisterhood

From the publisher: Male literary friendships are the stuff of legend, but what about the friendships of women writers? A Secret Sisterhood, drawing on letters and diaries, some never published before, brings to light a wealth of surprising female collaborations.

Here you’ll find the friendship between Jane Austen and one of the family servants, amateur playwright Anne Sharp; the daring feminist author Mary Taylor, who shaped the work of Charlotte Brontë; the transatlantic friendship of the seemingly aloof George Eliot and the ebullient Harriet Beecher Stowe; and Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, most often portrayed as bitter foes, but who, in fact, enjoyed a complex friendship.

They were sometimes scandalous and volatile, sometimes supportive and inspiring, but always — until now— tantalizingly consigned to the shadows.

More literary friendships

- Virginia Woolf & Vita Sackville-West

- Lillian Hellman & Dorothy Parker

- Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings & Zora Neale Hurston

- Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin

Leave a Reply