Gwendolyn Brooks, Esteemed American Poet

By Nava Atlas | On March 1, 2018 | Updated July 18, 2023 | Comments (0)

Gwendolyn Brooks (June 7, 1917 – December 3, 2000) was a highly awarded American poet whose works included sonnets and ballads as well as blues rhythm in free verse. She also created lyrical poems, some of which were book-length.

Arguably her most famous poem is the brief, much-anthologized “We Real Cool,” but it would be sad to stop there, as her career as a working poet were rich.

Though her work reflected urban Black life, its underlying themes were universal to the human experience. Gwendolyn Brooks’ lifetime output encompassed more than twenty books, including children’s books.

Gwendolyn Brooks biography highlights

- Gwendolyn experienced racism and bias from the time she was young, and this informed her poetic work as she progressed in her writing career.

- Her first collection of poetry, A Street In Bronzeville (1945), referring to an area in Chicago’s South Side, led to her receiving a Guggenheim fellowship.

- The 1949 collection Annie Allen (1949) earned her a Pulitzer Prize in 1950, making her the first African-American to win this award. With In the Mecca and The Bean Eaters, she continued to earn accolades.

- In 1968, she was named Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois, and from 1985 to 1986, she served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress.

- Later in her life, she taught at a number of prestigious colleges and universities.

- Gwendolyn used her poetry to delve deeply into American race issues and advocate for tolerance. Extraordinarily prolific, she wrote hundreds of poems and was honored with multiple prestigious awards during her lifetime.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Early life; a precocious poet

Gwendolyn Brooks was born in Topeka, Kansas. Her family moved to Chicago during the period known as the Great Migration, when African-Americans moved in great numbers to Northern cities. She started writing and reading classic authors and poets when she was young.

Poetry played a large part in Gwendolyn’s life from the time of her childhood. Her parents were firm believers in her talent and helped her nurture it from the start. In A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun, Angela Jackson offers this portrait of her subject as a young poet:

“Gwendolyn wrote poems a long time before she was published. She would sit on the top of the back steps and dream in poetry about the magic of sky and the mysteries of her future.

She wrote a poem a day from the time she was eleven. Sometimes two or three. She was devoted to her poetry because her mother believed in her ability, her gift for it.

When she was seven, she showed her mother her page of rhymes. Her mother was overjoyed, excited at the possibility of a poetic daughter who would conquer the segregated world with elegant and eloquent language. She, a schoolteacher, know how important it was to achieve in letters.

‘You’re going to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar!’ Keziah Wims Brooks exclaimed. And Gwendolyn believed this because her mother had said it was so.”

With such believing nurturers as her parents were, young Gwendolyn had free reign to explore, daydream, and express:

“Dreamed a lot. As a little girl I dreamed freely, often on the top step of the back porch — morning, noon, sunset, deep twilight. I loved clouds, I loved red streaks in the sky. I loved the gold worlds I saw in the sky. Gods and little girls, angels and heroes and future lovers labored there, in misty glory or sharp grandeur.”

“My father provided me with a desk…with many little compartments, with long drawers at the bottom, and a removable glass-protected shelf at the top, for books. Certainly, up there, holding special delights for a writing-girl, were the Emily of New Moon books, L.M. Montgomery’s books about a Canadian girl who wrote, kept notebooks even as I kept notebooks, dreamed, reached.”

Gwendolyn’s father read poetry and sang ballads to Gwendolyn and her brother. But there was just so much her parents could do to shelter her from racism, and these experiences also informed her poetic work in all stages of her writing career.

Gwendolyn’s first poem was published in a children’s magazine when she was thirteen years old. Subsequently, while still in her teens, some of her first poems were published in the legendary African-American newspaper, The Chicago Defender. She also participated in poetry workshops, which helped her writing career get off the ground.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gwendolyn with her husband and son, Milwaukee, 1945

. . . . . . . . . . .

Breaking into publication

In her mid-twenties, Gwendolyn won her first major award, and caught the attention of editors at two prestigious publishers. Imagine what it must have been like to have a choice between Alfred A. Knopf, and Harper and Brothers (today HarperCollins) for a first book of poems.

That was something that, despite today’s boom in poetry, would be a nearly impossible dream. By showing up to events, meeting editors and literary role models like Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn demonstrated not only her great talent, but her work ethic and determination.

In 1945, twenty-eight-year old Gwendolyn Brooks broke into book publishing with A Street In Bronzeville. The title refers to an area inhabited largely by African Americans in Chicago’s South Side, where she grew up. This poetry collection was quite well received and led to her receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Winning the Pulitzer Prize; some major works

Annie Allen (1949) earned a Pulitzer Prize in 1950, making Gwendolyn Brooks the first African American to win this award. The book follows the life of Annie, an Black girl, from birth to womanhood.

The poems reflect on the violence and racism that are part of Annie’s milieu, yet end with her hopes for a better world than the one she has inhabited.

The Bean Eaters (1960) was another well-received collection of poems. Critics such as the one who wrote this review noted her ability to tap into both specific and universal experiences:

“Her poems are clear, not because they are childishly simple but because they strike at the thought and feelings common to mature people.”

In the Mecca (1968) refers to an 1891 apartment building in the Chicago’s South Side, a fortress-like structure that deteriorated into a slum.

The first half of the book is a long poem about this environment, the second half consists of individual poems, the best known of which are “Malcolm X” and “Boy Breaking Glass.” It was nominated for the National Book Award for Poetry.

Maud Martha (1951) was Gwendolyn’s only novel. It wasn’t widely read when first published, but has gained respect over the years as a story that speaks to the challenges and joys in a mid-century black woman’s life, centering on universal themes.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha

. . . . . . . . . . .

Poet Laureate of Illinois and other awards

In 1968, Gwendolyn Brooks was named Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois. From 1985 to 1986 she was Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress.

Her work continued to be recognized for its excellence with prestigious awards, including those from the American Academy of Arts and Letters award, the Frost Medal, National Endowment for the Arts, The Shelley Memorial Award, and others.

A distinguished teaching career

Gwendolyn Brooks taught as part of her career, leading classes at Columbia College in Chicago, Northeastern Illinois University, Columbia University, and the University of Wisconsin. When she became a professor of English at Chicago State University in 1990, she held the position until her death in 2000.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The challenges of a writing mother

Throughout her career in the writing field, Gwendolyn maintained a family life, with a husband (whom she married in 1939) and their two children. When she was awarded the Pulitzer prize in 1950, she already had a young son, Hank, and about a year and a half later her daughter Nora was born.

In the 2017 biography, A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun, author Angela Jackson tells of the challenges the poet faced as a writer and mother.

Shortly after her daughter Nora was born, for example, Gwendolyn was supposed to travel to receive an award, but could’t find a babysitter for the children. Nora later recollected that her mother limited travels until she and her brother were a little older. According to Jackson:

“This is not to say she did not struggle between motherhood and writing. In December, 1951, when Hank was eleven and Nora a three-month-old infant, Gwendolyn confided in a letter to Langston Hughes that her duties and responsibilities as a mother were so overwhelming that she felt she was without time ‘to call my soul my own.’ She barely had a moment for herself, much less to write.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Read more about how she negotiated the balance between family life and writing in Gwendolyn Brooks: The Poet as Working Mother.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks used her poetic voice to spread tolerance and understanding the black experience in America. A prolific writer, she produced hundreds of poems, had twenty books published, and was recognized and honored with multiple prestigious awards during her lifetime.

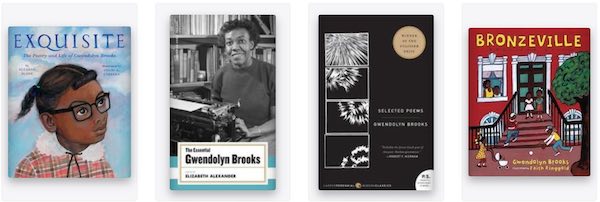

Yet despite her standing as a great American poet, many of her books are not easy to come by. It’s our hope that a wise publisher will change that, so that she can be more readily studied and appreciated. She died of cancer at the age of 83, in 2000.

. . . . . . . . . . .

6 Classic African-American Authors You Should Know More About

More about Gwendolyn Brooks

On this site

- Quotes on Writing and Life

- 5 Things to Love About Gwendolyn Brooks

- The Poet as Working Mother

- Poetic Quotes from Maud Martha

- 11 Iconic Poems by Gwendolyn Brooks

Major Works (selected)

- A Street in Bronzeville (1945)

- Annie Allen (1949)

- Maud Martha (1951)

- Bronzeville Boys and Girls (1956)

- The Bean Eaters (1960)

- Selected Poems (1963)

- In the Mecca (1968)

- Riot (1969)

- Primer for Blacks (1980)

- Young Poet’s Primer (1980)

- To Disembark (1981)

- The Near-Johannesburg Boy and Other Poems (1986)

- Blacks (1987)

- Winnie (1988)

- Children Coming Home (1991)

Autobiographies, Biographies, and Literary Criticism

- A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun by Angela Jackson

- Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks – edited by Gloria Wade Gayles

- The World of Gwendolyn Brooks

- Report From Part One: An Autobiography

- A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks by George Kent

- On Gwendolyn Brooks: Reliant Contemplation by Stephen Caldwell Write

- The Poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks – an Analysis by David Wheeler

- Maud Martha: A Critical Collection by Bryant and Blakely

More Information

- Wikipedia

- Library of Congress Online Resources

- The Poetry Foundation

- Modern American Poetry: Gwendolyn Brooks

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Poetry Foundation: From the Archive

- The Roads Taken

- Sweet Bombs: A review of The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks

- Remembering the Great Poet Gwendolyn Brooks at 100 (NPR)

- An interview with Gwendolyn Brooks (video)

Visit and research

- Gwendolyn Brooks Grave – Lincoln Cemetery, Blue Island, IL

- Gwendolyn Brooks Center – Chicago State University, Chicago, IL

Leave a Reply