The Friendship of Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wylie

By Katharine Armbrester | On February 12, 2024 | Updated September 3, 2024 | Comments (0)

When one thinks of Jazz Age literature, novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald or D. H. Lawrence might come to mind. Lyrical and provocative poetry was also part of Roaring Twenties culture. Two of the most beloved and provocative poets of the 1920s were Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wylie.

Both Millay and Wylie were dedicated lyrists and writers, despite their tempestuous personal lives. They both navigated the pitfalls of fame, scandal, and illness – all while leaving an indelible mark on American poetry.

Background: Elinor Wylie

The poet and novelist Elinor Wylie was born in Somerville, New Jersey on September 7, 1885. She was born into an affluent family marred by personal tragedy. Her parents’ marriage was deeply unhappy, and two of Elinor’s siblings committed suicide, with a third sibling attempting it.

Elinor’s father was a high-profile lawyer who became Solicitor General of the United States in 1897. Elinor grew up in Washington, D.C. from the age of twelve.

Elinor’s godfather was a Shakespeare scholar named Henry Howard Furness. Unusually for the time, he insisted that his goddaughter have the best education possible, including European governesses.

A beloved Irish maid instilled a love of folk tales in Elinor, and a teacher at her private school introduced her to the poetry of William Blake, John Donne, and Percy Bysshe Shelley; the latter would remain her greatest inspiration and favorite poet.

When Elinor showed an inclination towards being a “blue-stocking” (a common pejorative for an intellectual or career-minded woman) her parents were horrified. Elinor was supposed to be a debutante and have a dazzling society marriage.

In 1905, Elinor married an aspiring poet named Phillip Hichborn, but soon after the marriage he began falling into rages and displaying signs of mental illness. Sadly, he committed suicide in 1916. Many years later his and Elinor’s only child—also named Phillip, also a hopeful poet, and also possibly suffering from mental illness—met the same end as an adult.

A prominent, and married, Washington lawyer named Horace Wylie pursued Elinor. The two ran away in 1910, leaving behind their spouses and children. The two were condemned by society, and knowingly or not, Elinor had followed in Shelley’s footsteps. For the rest of her life her literary achievements were rarely noted without also mentioning this scandal.

. . . . . . . . . .

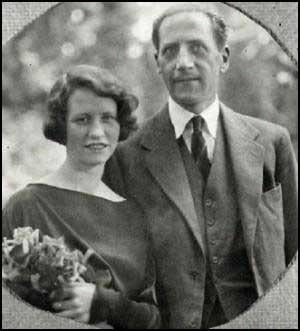

Elinor Wylie

. . . . . . . . . .

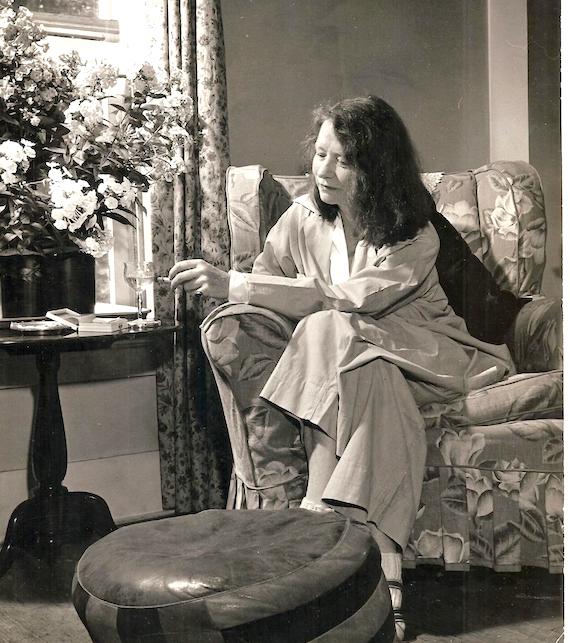

Background: Edna St. Vincent Millay

The poet and playwright Edna St. Vincent Millay was born in Rockland, Maine on February 22, 1892. Her parents separated when she was young, and her father gave little financial support to the three children he left behind.

Millay’s mother, Cora, was a strong-willed woman and supported her daughters by her work as a traveling nurse and occasional wigmaker. “The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver” was one of the poems that contributed to Millay’s eventual Pulitzer Prize, and it is a moving tribute to her sacrificial mother. It was one of the favorite poems of singer Johnny Cash, and he recited it from memory on his television show in 1970.

Cora frequently had to take work away from home, leaving her three daughters alone for days at a time in their seaside home in Camden, Maine. Due to their mother’s absences, Millay and her younger sisters, Norma and Kathleen, were extremely close knit. All three were musically gifted, with great charm, intense inner lives, and varying shades of red hair.

Despite being a voracious reader and a precocious writer, Millay’s first ambition was to be a concert pianist. She was eventually told that her hands were too small, she then shifted her focus to writing poetry, both as a means to support her family and as a way to make a mark on the world.

She wrote: “Life is brown and tepid for many of us. I want to write so that those who read me will say… ‘Life can be exciting and free and intense.’”

In 1912, at the young age of twenty and hitherto very isolated, Millay was able to write the long poem “Renascence” with its lines of startling boldness, maturity, and emotional depth:

Mine was the weight

Of every brooded wrong, the hate

That stood behind each envious thrust,

Mine every greed, mine every lust.

The poem was entered into a national competition to be included in an upcoming anthology, the Lyric Year. Although she did not win first prize, the poem skyrocketed Millay into the literati of the period. With the help of a patron, she attended the prestigious Vassar College. While there, Millay studied classical poetry, racked up broken hearts among her younger classmates, and nearly got expelled just before graduation. Afterwards, she headed for New York City.

. . . . . . . . . .

Edna St. Vincent Millay in her college days

. . . . . . . . . .

Elinor Wiley: Scandals and Success

Elinor married Horace Wylie in 1916 after he obtained a divorce from his wife. Due to her lover’s encouragement, Wylie anonymously published her first book of poetry in England in 1912, Incidental Numbers. After the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the disgraced couple returned to the United States, frequently moving due to social ostracism.

Wylie’s poetry began to be published in multiple magazines, and early admirers of her poetry were novelists Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, and the young Ernest Hemingway. She befriended writers John Peale Bishop and Edmund Wilson, who were also devoted friends of Millay. She also met the widowed poet William Rose Benét.

Both Benet and his brother Stephen Vincent would later win Pulitzer Prizes for poetry, William in 1942 and Stephen in 1944. William took it upon himself to advance Wylie’s literary career, and the two fell in love, which led to the end of Wylie’s second marriage.

Wylie’s brother Morton Hoyt married and divorced Eugenia Bankhead, the sister of the controversial actress Tallulah, a total of three times. When Bankhead once asked Wylie if she had had many lovers, the latter icily replied that “she was conservative about love and had simply married when she had experienced it.”

Wylie struggled to be taken seriously as a poet, which was made even more difficult by her unconventional past. She possessed great determination and once responded to her critics with, “I have a typewriter and a better brain them all of them, and they won’t succeed. I’ll beat them all yet!”

In 1921, Nets to Catch the Wind was published, Wylie’s first volume of poetry printed in the United States. The writer Babbette Deutsch called Nets “almost one uninterrupted cry to escape.” It is generally considered to contain many of her greatest poems, particularly “The Eagle and the Mole” and “A Proud Lady.”

“The Eagle and the Mole” is one of Wylie’s most beloved and anthologized poems, and vividly describes conformity (“The huddled warmth of crowds / Begets and fosters hate”) while offering a balm for the nonconformist’s inevitable rejection by their peers:

Avoid the reeking herd,

Shun the polluted flock,

Live like that stoic bird,

The eagle of the rock.

Similarly, in “A Proud Lady” she describes the “hate in the world’s hand,” a scornful hate she was well acquainted with, and a hate she defied with her poems:

But you have a proud face

Which the world cannot harm,

You have turned the pain to a grace

And the scorn to a charm.

You have taken the arrows and slings

Which prick and bruise

And fashioned them into wings

For the heels of your shoes.

Millay reviews Wiley’s Nets to Catch the Wind

Millay—who by now had weathered stormy relationships with both men and women and was likewise committed to pursuing her art at any cost—undoubtedly found much in Wylie’s verses that resonated with her struggle for artistic freedom.

In her poem “Weeds” she described the hateful outside world as “The baying of a pack athirst.” She enthusiastically reviewed Nets to Catch the Wind in the Literary Review.

“The book is an important one,” Millay wrote, “important in itself as it contains some excellent and distinguished work and…because it is the first book of its author, and thus marks the opening of yet another door by which beauty may enter the world.”

Millay’s biographer Daniel Mark Epstein writes that Millay’s glowing review “launched Wylie’s career in the 1920s as a love poet second only to Millay herself, who proved memorably generous to spirits with whom she felt artistic kinship such as Wylie.”

1922 – the start of Millay and Wylie’s friendship

In 1922 the literary critic and writer Edmund Wilson introduced Wylie to Millay, who was a former girlfriend he was still pining for. Epstein writes that “From the day Millay met Wylie, the two women were devoted to each other, corresponded, and visited each other’s homes.”

Alas, there appear to be no photographs of the two women together. They would have made a striking pair: Millay, petite and freckled with red-gold hair and Wylie, tall, aloof, and regal with dark auburn hair. Both were known for their tousled bobs and preference for simply cut gowns in rich fabrics.

Both poets briefly wrote for the popular magazine Vanity Fair, and both published their first poetry collections after leaving the place of their births. Millay publishing Renascence and Other Poems after moving to the bohemian Greenwich Village, and Wylie publishing Incidental Numbers after her shocking elopement to England.

Along with having heartbreak, rejection, and red hair in common, the two writers shared similar themes and techniques in their poetry oeuvre. Both belonged to the lyric genre of poetry, which was known for its focus on nature and loyal adherence to the more traditional forms of poetry such as elegies, odes, and sonnets.

They were not always in agreement with each other. Millay strongly disapproved of Wylie’s imitation of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats in her poem “Madman’s Song.” Both writers, despite this the two had much in common, such as their social backgrounds.

Poetry was their preferred medium, but they also wrote in other genres to support themselves. While living in Greenwich Village, Millay also acted in the Provincetown Players (which included writers Djuna Barnes and Susan Glaspell) and wrote several plays, including the very successful Met Opera libretto The King’s Henchman.

Wylie wrote four novels, including The Venetian Glass Nephew, set in Renaissance Italy, and The Glass Angel, in which she decided to give her beloved Shelley a different fate than his untimely death (the novel is undoubtedly a very poetic work of fan fiction).

Wylie adored Shelley so much that she purchased several of his personal effects with her royalties from The Orphan Angel, and Benét wrote that his wife was “spontaneous and baffled [like Shelley] by the matter-of-factness of the world.” After Wylie’s death Millay wrote in a poem dedicated to her friend: “I think that…Shelley died with you–) / He live[s] on paper now, another way.”

In 1923 Wylie saw the publication of both her novel Jennifer Lorn and her poetry collection, Black Armour. 1923 was also a big year for Millay: she married the wealthy, handsome, and supportive Dutch merchant Eugen Boissevain.

After the wedding (donning a stunning green dress with mosquito netting for an impromptu veil) Millay promptly entered the hospital for appendicitis surgery. Soon afterwards she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, becoming the first woman recipient of the newly established honor.

In 1927, the League of American Penwomen asked Wylie to be a guest of honor at an author’s breakfast in Washington, D.C. They later canceled their invitation due to Wylie’s personal history, and an incensed Millay wrote them a letter, sending a copy of it to Wylie.

Millay was invited to the same event and wrote to the League of her decision to decline: “It is not in the power of an organizations which has insulted Elinor Wylie to honor me…I too am eligible for your disesteem. Strike me too from your lists, and permit me, I beg you, to share with Elinor Wylie a brilliant exile from your fusty province.”

In her diary, Millay raged against the insult to her friend, writing “I wished I had been a Fifth Avenue street sparrow yesterday—or in other words:

I wish to God I might have shat

On Mrs. Grundy’s Easter hat.

“Mrs. Grundy” was a popular term at the time for a priggish, prudish person—similar to today’s usage of the name “Karen” to describe a middle-class woman who polices behavior. Millay, with her own colorful past, despised women who judged or undermined other women.

In gratitude for Millay’s solidarity, Wylie responded: “My darling—A thousand thanks for your brilliant and noble defense…I have written you a ballad—to you—which perhaps you’ll like. Hope so, at least.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“To Hold Secure the Province of Pure Art”:

Shared Poetry Subjects

In her writing, Millay aspired “To hold secure the province of pure art” and to craft “the deeply loved, the labored polished line,” and these were undoubtedly Wylie’s aspirations as well. They pursued the writing of poetry with unwavering commitment, and refused to associate with those who did not take their work seriously. It also appears that, commendably, they were not jealous of each other’s achievements.

Wylie was an aesthetic writer, which critics frequently and disparaging commented on, and she labored to craft indelible images with her verse. Delicate objects d’art was a frequent motif in her poetry, and lavishly described colors and textures.

Millay crafted haunting descriptions of nature as well but appeared more dedicated to crafting a poem that resonated with musicality, perhaps fitting for a failed concert pianist. The few recordings available of Millay reading her poetry bring out the musical nature of her verses, and with her deep voice her poems sound like songs.

Holly Peppe, a former president of the Millay Society, wrote that “Whether her subject was nature, love, loss, spiritual rebirth, personal freedom, women’s sexuality, or the state of the world, Millay was always conscious of how musicality in poetry would help deliver its message.”

Both Wylie and Millay gravitated to poems with short lines and stanzas, and both frequently wrote about the beauties of nature and about love affairs that were less than satisfactory, but these were not the only poetry subjects that they shared.

Fully aware that their own singular looks and allure would fade Wylie and Millay had ambivalent views about beauty, which they both painted as possessing human characteristics.

Wylie wrote of beauty in the eponymous poem:

O, she is neither good nor bad,

But innocent and wild!

Enshrine her and she dies, who had

The hard heart of a child.

In her poem “Assault” Millay writes of beauty:

I am waylaid by Beauty. Who will walk

Between me and the crying of the frogs?

Oh, savage Beauty, suffer me to pass,

That am a timid woman, on her way

From one house to another!

Both meditated on the inevitability of death with quiet reflection; both appear to have regarded it as natural a fact as sleep.

When I am dead, or sleeping

Without any pain

My soul will stop creeping

Through my jewelled brain. (Wylie’s poem “Song”)

And here a while, where no wind brings

The baying of a pack athirst,

May sleep the sleep of blessèd things,

The blood too bright, the brow accurst. (Millay’s poem “Weeds”)

However, Millay also memorably protested against death in one of her most emotionally charged poems “Dirge Without Music”:

Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

Although it appears Wylie and Millay did not refer to themselves as flappers, both were unabashedly avant-garde, and both wrote honestly about women and their experiences in a beautiful and dangerous world.

As if singing in a duet, Millay wrote in her poem “I, being born a woman and distressed / By all the needs and notions of my kind” and Wylie echoed the thought, “I am, being woman, hard beset;/ I live by squeezing from a stone / What little nourishment I get.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“The Blood too Bright, the Brow Accurst”:

Death Comes for the Poets

Both Wylie’s and Millay’s poetry was wildly popular among the public, which may have been a reason that critics frequently took aim at their women-centric verse. Another reason for criticism was likely due to their uncompromising unconventionality.

Neither Wylie or Millay believed in compromising their hunger for passion, or with subduing their ambition to be great poets. Both women were identical in their belief that love was worth pursuing, no matter what convention and society decreed, no matter the personal cost.

Had I concealed my love

And you so loved me longer,

Since all the wise reprove

Confession of that hunger

In any human creature,

It had not been my nature. (Wylie, “Love Song”)

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution’s power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would. (Millay, Sonnet XXX)

Even some of Wylie’s poet contemporaries, including Sara Teasdale, could not or would not separate Wylie’s tangled personal life from her polished writing. Despite her own unconventional personal life, the poet Amy Lowell threatened Wylie shortly before marrying Benét. “But if you marry again, [I] shall cut you dead‐and I warn you all Society will do the same. You will be nobody.”

There was a notable double standard. Wylie’s career was damaged, while her near contemporary Ernest Hemingway who, despite a catastrophic personal life, is still regarded as an extraordinary writer and soundly admired for his iconoclasm.

After marrying Benét, he and Wylie frequently visited Steepletop, the home of Millay and the devoted Boissevain. The lovely country abode in upstate New York, which is currently not open to visitors, was named after the pink steeplebush wildflower that bloomed on the property.

The two women read poetry in front of a fire, intensely discussing the poems “St. Agnes Eve” and “Epipsychidion.” Wylie read Shelley’s poem the “West Wind” aloud and cried out to her friend, “The best poem ever written!”

The next day Wylie read her own novel Mortal Image (perhaps with a critical eye, hoping for reassurance from a fellow writer) while Millay played “first Chopin, then Bach, then Beethoven on the piano. I play so badly. But not too badly, I think, to be not allowed to play them. It was fun, Elinor there reading, & listening too.”

The uplifting literary friendship would soon end. Millay once wrote to her mother, “You see, I am a poet, and not quite right in my head, darling.” She was increasingly troubled by “extravagant depression” and a plethora of health problems. Likewise, Wylie suffered from extremely high blood pressure all her life, which caused crippling migraines, and eventually her death.

On December 16th, 1928, Wylie, who had just finished proofreading her last volume of poems, Angels and Earthly Creatures, asked aloud “Is that all it is?” and suddenly died of a stroke.

The day after, Millay was casually told of her friend’s passing right before she was to give a poetry reading. “Stunned, shaken, Millay made her way to the podium and, waving aside the fanfare and applause, began reciting Wylie’s verses, poem after poem, from memory.”

Millay’s next book was dedicated to her friend:

When I think of you,

I die too.

In my throat, bereft

Like yours, of air,

No sound is left,

Nothing is there

To make a word of grief.

Wylie was “so gay and splendid about tragic things, so comically serious about silly ones,” wrote Millay, “Oh, she was lovely! there was nobody like her at all.” Millay attended Wylie’s funeral, and the latter was buried in her favorite silver gown by Poiret.

Judith Farr, the poet and Emily Dickinson scholar wrote that, “the career of Elinor Wylie is remarkable for what might be called intensity of performance.” Her poetry likely influenced Millay’s collection Fatal Interview, a collection of sonnets that was published three years after Wylie’s death and was dedicated to her. Fatal Interview relates the history of a tragic love affair just as in Wylie’s “one person” sonnet sequence in Angels and Earthly Creatures.

Oh, she was beautiful in every part!

The auburn hair that bound the subtle brain;

The lovely mouth cut clear by wit and pain,

Uttering oaths and nonsense, uttering art…

The soaring mind outstripped the tethered heart.

After sustaining a severe back injury in a car accident in 1936, Millay became addicted to morphine, as well as alcohol. However, she did successfully break her addiction and resumed writing.

Her husband died in 1949 after, like Wylie, suffering from a stroke following lung surgery. Millay spent the next year preparing a new volume of poetry but passed away in 1950 after suffering a heart attack. Mine the Harvest was published posthumously four years later.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Legacy of Two Red-Headed Rebels

The verse of Millay and Wylie was largely separate from the Modernist movement, which included the poets T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. This earned criticism from both contemporary and subsequent literary critics, who frequently accused Millay and Wylie’s poetry as being too old-fashioned or “sentimental.”

In retrospect, their poetry has aged better than some by the lionized Modernist poets Eliot and Pound, who were both notoriously anti-Semitic and often chauvinist. Much of Millay’s poetry written during the 1940s fervently condemned fascism and championed democracy, and she often recited her verses on the radio during World War II.

Millay and Wylie were dedicated to portraying the varied experiences of women in a man’s world, and many of their poems, both lyrical and grimly realistic, are still relevant today.

In 1931, three years after Wylie’s death, Millay wrote about women’s’ struggle in pursuing careers in the arts, words that her friend would likely have agreed with:

“What you produce, what you create must stand on its own feet regardless of your sex. We are supposed to have won all the battles for our rights to be individuals, but in the arts women are still put in a class by themselves, and I resent it, as I have always rebelled against discriminations or limitations of a woman’s experience on account of her sex.”

Further Reading and Sources

- Poetry Foundation – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Steepletop Museum

- What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay

by Daniel Mark EpsteinSavage Beauty by Nancy Milford - The Life and Art of Elinor Wylie by Judith Farr

- A Private Madness: The Genius of Elinor Wylie by Evelyn Hively

- Elinor Wylie: A Life Apart by Stanley Olson

- Poetry Foundation – Elinor Wylie

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Katharine Armbrester, who graduated from the MFA creative writing program at the Mississippi University for Women in 2022. She is a devotee of Flannery O’Connor and Margaret Atwood, and loves periodicals, history, and writing.

Leave a Reply