Emily Dickinson, Esteemed American Poet

By Nava Atlas | On July 12, 2017 | Updated August 17, 2022 | Comments (0)

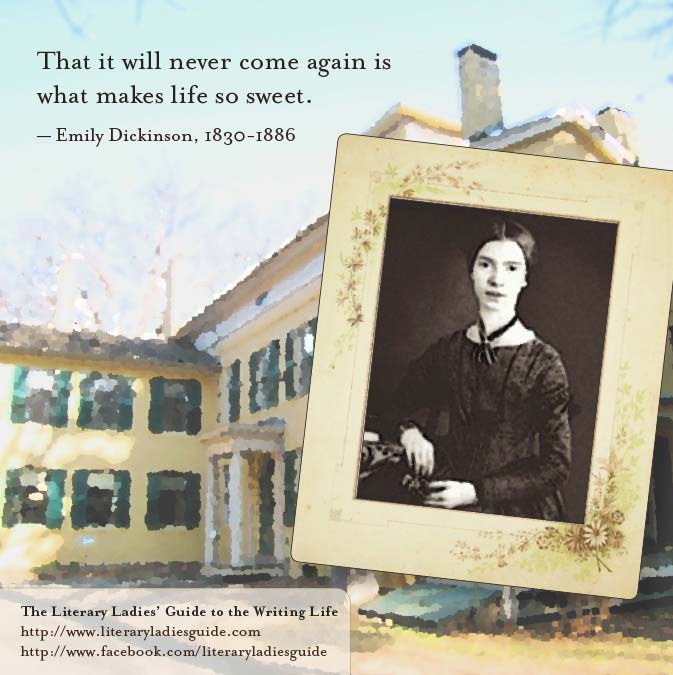

Emily Dickinson (December 10, 1830 – May 15, 1886) was a prolific American poet. Though she wrote more than 1,800 poems by some estimates, only a few were published during her lifetime. She is still something of a mystery, which fuels the continued fascination with her work and life.

“Tell all the truth but tell it slant —” is one of her famous lines, and the truths revealed in her poetic works are as individual as the person who reads them.

Dickinson grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts. She was born, lived, and died in the same house. While popular mythology has it that she rarely formed relationships with anyone outside her immediate family, this is not quite accurate.

As a girl and young woman, she had an active social life and was an ardent correspondent. And while something did indeed shift somewhere in the middle of her life, she was not so reclusive as myth would have it.

Her father, a prominent lawyer, ensured that the family had a notable standing in the community. The family included her mother, her sister Lavinia, and brother Austen. As a child, Emily studied at Amherst Academy as did Lavinia and Austin, growing up in a somewhat Puritan milieu.

Mixed messages on education for women

Though Emily Dickinson’s father believed in education for women, he also felt that this education shouldn’t be used toward any pursuits other than caring for the home, husband, and children. She said of him, “He buys me many books, but begs me not to read them, because he fears they upset the mind.”

Emily left home briefly at the age of sixteen to study at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, Massachusetts. She roomed with her cousin Emily Norcross and studied botany, chemistry, languages, and history. Her educational sojourn is well documented, as she corresponded regularly with her brother Austin and good friend Abiah Root.

For women of this time and place, spending just one year in higher education was common, and that is just what Emily did. She returned to the family home in Amherst at the end of the academic year.

Emily’s interest as an amateur botanist

In addition to her talent for writing, Emily displayed a keen interest in plants and gardens from a young age. She began compiling a herbarium — an album of pressed flowers and leaves — when she was just eight or nine years old. She arranged these cuttings in the album with much attention to design as well as scientific classification.

The fragile album has been digitized and is occasionally on display in this form, in exhibits about the poet and her life.

Emily seemed to have completed the album before her year at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, and continued her interest with formal courses in botany. Throughout her life, she loved gardening, and the natural world was often part of her poetry.

. . . . . . . . . .

Preserving Nature: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium

. . . . . . . . . .

Developing her identity as a poet

It was during the Civil War that Emily developed her identity as a poet. Between the late 1850s and the early 1860s, she spent a great deal of time with her close friend Susan Huntington Gilbert, whom her brother Austin married.

Emily sent some of her poems to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a noted literary figure. His critique of her unorthodox style seemed to discourage her, and she retreated to the habit of keeping her writing private. Nevertheless, she continued to write copiously. In The Penguin Companion to American Literature (1971), Eric Mottram offered this assessment of her poetic practices:

“She hoarded her poems, among them love poems, apparently addressed to Benjamin Newton, a student in her father’s office, with whom she corresponded until his death in 1853, and Charles Wadsworth, a distinguished married clergyman who may have left America because of her.

… ‘Pardon my sanity in a world insane,’ she wrote in a letter, a clue to her need to create a balanced life out of her passion and intellectual clarity.

In 1863 she probably wrote about 140 poems, and in 1864 nearly 200, the high point of her prolific output of about 1,775 poems, all written within the characteristic late 19th-century range of relationships between God, man, and nature. Since she did not have the pressures of publication, her style is remarkably free, intense, and idiosyncratic, the exact form of her complex personality.

Her weakness is a reliance on rhythmic cadences and meters from hymns and popular jingles. She was not a prosodic innovator, although her punctuation, derived from reading and pronunciation handbooks, looks odd.

And her imagery continually startles with its freshness and penetration. Her modernity is her articulation of psychological experience and skeptical desire for faith.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Emily, Austin, and Lavinia Dickinson as children

. . . . . . . . . .

“Deepening menace” of death

Dickinson was haunted by a “deepening menace” of death from a young age and was traumatized by the death of her loved ones. She describes this effecting her as “The Crisis of the sorrow of so many years is all that tires me.”

Religion provided solace and the theme of loss inspired her writing. She didn’t produce work to publish, make money, or gain fame; she cared only to share her thoughts and writings with those close to her.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Poetic inspiration and a pervasive mythology

After living in Cambridge, Massachusetts for a short time to receive an eye treatment, Emily moved back to her homestead permanently, where she began writing copiously. Despite living a rather sheltered life, her poetry reveals a deep understanding of love, loneliness, the natural world, and human nature in all its glory and sadness.

Emily was inspired by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Reverend Charles Wadsworth, John Keats, and Walt Whitman. Her life and mythology, some perpetuated by the poet herself, have been reduced to an all-too-simple picture of a sad, isolated girl-woman.

One of her main biographers, Lyndall Gordon, worked to overturn persistent myths about the poet, writing in a 2010 article in The Guardian, “A Bomb in Her Bosom: Emily Dickinson’s Secret Life”:

“On the face of it, the life of this New England poet seems uneventful and largely invisible, but there’s a forceful, even overwhelming character belied by her still surface. She called it a “still – Volcano – Life”, and that volcano rumbles beneath the domestic surface of her poetry and a thousand letters. Stillness was not a retreat from life (as legend would have it) but her form of control. Far from the helplessness she played up at times, she was uncompromising; until the explosion in her family, she lived on her own terms.”

The “explosion in her family” refers to the betrayal by her brother, Austen Dickinson, of his wife Susan, with his passionate love affair with Mabel Loomis Todd.

Discovering a trove of Emily’s poems after her death

On May 15, 1886, after several days of illness, Emily Dickinson died in her home at age 55. It’s believed that she may have died of kidney disease.

After her death, over a thousand poems were discovered by her younger sister Lavinia, a lifelong companion of Emily’s who lived a similar lifestyle. By some estimates the number of poems were 1,100; other sources state that it was closer to 1,800.

Dozens if not hundreds of her unpublished poems were shared with friends in correspondence. Dickinson kept her hand-sewn manuscript books entirely to herself.

The poems were edited and published to fit the conventional rules of the era. Lavinia first turned the poems over to Susan Dickinson to edit and publish them, but the work was painstaking. Lavinia turned the poems over to Mabel Loomis Todd, Austen Dickinson’s mistress, who dedicated much of the rest of her professional life to editing and publishing the poems.

Four years after Dickinson’s death, the first volume her poems were published in 1890, and later, augmented editions came out in 1891 and 1896. Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Emily Dickinson’s literary mentor, took on the role of co-editor. There were many challenges in interpreting and transcribing the poems, but within 10 years, her literary reputation was established.

. . . . . . . . . .

The Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, MA,

is open for tours in March – December of each year

. . . . . . . . . .

Emily Dickinson’s legacy

It wasn’t until the twentieth century that Dickinson was given her due as a great poet. Shortly after the first World War, her stature in the world of American letters rose significantly.

But it could be argued that her life and art weren’t fully understood and fleshed out until Thomas H. Johnson’s Emily Dickinson: An Interpretive Biography was published in 1955. The most comprehensive collections of her letters and poems to be compiled to that date, it let the world in on the full scope of her genius. As the book describes:

“Here the complex pattern of emotional forces within the Dickinson family is revealed, and the constantly disturbing outer world reaches in to Emily Dickinson through the personalities of her chosen three—Colonel Higginson, the Reverend Charles Wadsworth, and Helen Hunt Jackson.

For this remarkable and moving book the author has been able to examine and assess all the information concerning Emily Dickinson that is known to exist, something that had not been possible until now.

Emily Dickinson lives in these pages as she must have lived in Amherst, a product of the Connecticut Valley—part of it but always beyond it: an original spirit who constructed a universe out of materials infinitely small. As they emerge here from her life her poems speak for her and describe her as audacious, witty, passionate, deliberately elusive, and supremely courageous.”

Emily Dickinson has unquestionably earned her place as one of America’s most beloved poets.

. . . . . . . . . .

10 Well-Loved Poems by Emily Dickinson

More about Emily Dickinson on this site

- 10 Well-Loved Poems by Emily Dickinson

- Emily Dickinson quotes

- A Quiet Passion: Reviews of the 2017 film

- “Sic transit gloria mundi” — Emily’s first published poem

- Preserving Nature: Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium

- Enigmatic Recluse or Sheltered Genius? A Tribute to Emily Dickinson

Major Works (Collected)

- The Essential Emily Dickinson, selected and with an introduction by Joyce Carol Oates (2016)

- Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them, Christianne Miller, ed. (2016)

- The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, Thomas Johnson, ed. (1976)

Biographies and criticism (selected)

- Emily Dickinson: A Biography by Connie Ann Kirk (2004)

- Emily Dickinson and the Art of Belief by Roger Lundin (2004)

- Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family’s Feuds by Lyndall Gordon (2011)

- Emily Dickinson as a Second Language: Demystifying the Poetry by Greg Mattingly (2018)

- Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life by Marta McDowell (2019)

More Information and sources

- Wikipedia

- Poets.org

- Poetry Foundation

- Emily Dickinson’s Letters (The Atlantic, October 1891)

- Emily Dickinson’s Electric Love Letters to Susan Gilbert

Visit

- The Emily Dickinson Museum – Amherst, MA

Leave a Reply