Edna St. Vincent Millay, Groundbreaking American Poet

By Nava Atlas | On May 10, 2018 | Updated April 28, 2025 | Comments (0)

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American poet long regarded as a major twentieth-century figure in the genre.

Wildly popular in her lifetime, she fell out of favor after her death, but is now being reconsidered — read, studied, and growing (or re-growing) in regard in the field of poetry.

Her middle name really was an homage to the New York City’s St. Vincent’s hospital, where the life of an uncle was saved before she was born. After her parents were divorced, there was minimal contact with their father. Her mother, Cora, was frequently away from home, on the road as a visiting nurse.

Edna (who nearly her whole life went by the name of Vincent, so that’s what we’ll call her here) and her sisters Norma and Kathleen were raised near coastal Maine by their single mother, who taught them to value independence and appreciate literature, visual art, and music.

The sisters were often left to their own devices, and made the best of the situation, turning their tasks into games. Vincent’s forays into make-believe grew into a penchant for acting, which she did often and enthusiastically from childhood through her college years.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Voracious reader and precocious poet

Encouraged by her mother, Vincent immersed herself in great works of literature from an early age. She read Shakespeare, Keats, Longfellow, Shelley, and Wordsworth.

At age of sixteen she compiled a dozen or so poems into a copybook and presented them to her mother as “Poetical Works of Vincent Millay.” The poems were mainly sonnets, a form that she would favor throughout her life as a poet.

In 1912, encouraged by her mother, 19-year-old Vincent sent her poem, “Renascence” to The Lyric Year, a magazine that held a yearly poetry contest and published winning entries.

The narrator of the poem writes from a mountaintop from which she observes the broad vista. Its lines consider human suffering and death, and after a refreshing rain, the narrator is once again able to experience joy and a rebirth of life — thus the title, “Renascence.”

The poem was accepted and included in the collection. Though it took only fourth place (causing quite a scandal), it caught the attention not only of readers who felt that Vincent was robbed of the top prize, but of Caroline Dow, a wealthy patron of the arts.

Taken with Vincent’s passion for poetry, Dow arranged to pay her tuition to attend Vassar College. She would otherwise not have been able to afford college.

. . . . . . . . . .

The iconic poem “Renascence” by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . . .

Vassar College and Greenwich Village

Vincent entered college at age 21, and soon became aware of her power to attract, and used this to her advantage. According to J.D. McClatchley, editor of Edna St. Vincent Millay: Selected Poems (2002):

“‘People fall in love with me … and annoy me and distress me and flatter me and excite me.’ And she responded in kind; there were torrid affairs with girls at school, adding to her campus notoriety, and tepid flings with older men who might help her career. Throughout her life, she did what she felt she must do in order to create the conditions necessary to accomplish her work.

After Vassar, she became the Circe of Greenwich Village. She was soon the talk of the town. She drank and partied and had affairs, and thereby was the envy of all, and to young women in particular she was the free spirit that American Babbitry had stifled.

Her affairs were sometimes of the heart, and sometimes more practical. The writers she took as lovers (and invariably kept as friends afterward) … were in a position to both teach and help her. And she had always been a quick study. The poems she wrote then — wild, cool, elusive — intoxicated the Jazz Babies. She had found the pulse of the new generation.”

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends —

It gives a lovely light!

. . . . . . . . . .

Quotes by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . . .

An outpouring of poems; a feminist slant

A Few Figs from Thistles, her first major collection (1921), explored, among other themes, love and female sexuality. Second April (also 1921) dealt with heartbreak, nature, and death — the latter being a topic she explored often.

It’s rare for a poet to attain what we now call superstar status, but that’s just what Vincent was. Throughout the 1920s — call them Roaring or the Jazz Age — she recited to enthusiastic, sold-out crowds during her many reading tours at home and abroad.

Interspersed were head-spinning numbers of love affairs with both men and women. She was open about her bisexuality, which was unusual for the time.

In Europe, she posed for surrealist photographer Man Ray and dined with the artist Constantin Brancusi. It was a heady time indeed, and the candle she burned at both ends was still glowing.

Pulitzer Prize and an unconventional marriage

In 1923, Edna St. Vincent Millay won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry for her fourth volume of poems, The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver. She was only the second person to receive a Pulitzer for poetry, and the first woman to win the prize.

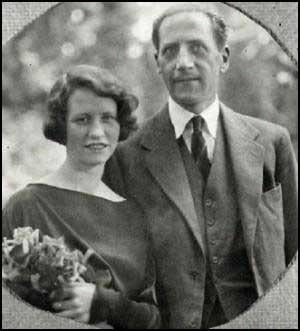

That year, Vincent also embarked on an unconventional marriage with Eugen Jan Boissevain. The handsome Dutch importer was a kindhearted man twelve years her senior, and she married him when, as her erstwhile lover Edmund Wilson saw it, “she was tired of breaking hearts and spreading havoc.”

Boissevain provided the support and stability Vincent needed for her writing. But she wasn’t one to settle down, after all. Both she and her husband took other lovers throughout their marriage.

Boissevain completely supported her career, even taking on many domestic duties and organizing their social life at the country home they purchased together, a 700-acre farm called Steepletop in Austerlitz, NY.

. . . . . . . . . .

Edna St. Vincent Millay and Eugen Jan Boissevain in 1923

. . . . . . . . . .

Political causes and protest

Vincent didn’t shy away from political causes. Her New York Times obituary describes her protest against the famed Sacco and Vanzetti affair:

“In the summer of 1927 the time drew near for the execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Boston Italians whose trial and conviction of murder became one of the most celebrated labor causes of the United States. Only recently recovered from a nervous breakdown, Miss Millay flung herself into the fight for their lives.

A poem which had wide circulation at the time, ‘Justice Denied in Massachusetts,’ was her contribution to the fund raised for the defense campaign. Miss Millay also made a personal appeal to Governor Fuller.

In August she was arrested as one of the “death watch” demonstrators before the Boston State House … ‘I went to Boston fully expecting to be arrested — arrested by a polizia created by a government that my ancestors rebelled to establish,’ she said, when back in New York.

‘Some of us have been thinking and talking too long without doing anything. Poems are perfect; picketing, sometimes, is better.’”

. . . . . . . . . .

12 Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . . .

Writing prolifically while wreaking havoc

Vincent continued to push boundaries in her writing and her personal life. Her anti-war play Aria da Capo was performed to sell-out crowds on Cape Cod by the Provincetown Players.

Her obsession with the shy young poet, George Dillon, who was gay, inspired one of her finest volumes of poetry, Fatal Interview. Published in 1931, it sold a stunning 50,000 copies in the first months of publication, a rarity for a book of poems, and during the Great Depression, at that.

Vincent seemed to need to create chaos to thrive. According to literary critic J.D. McClatchley:

“Millay spared no one — least of all herself — in her drive to create the kind of ‘havoc’ her poems feed on, and then to surround herself with the solitude to work that chaos into shimmering lines … Scandal, of course, only enhanced her celebrity … For women, she made complicated passion real; for men, she made it alluring.”

Life had becoming more fraught for the free-spirited poet as she reached middle age. While in Florida on working vacation with her husband, she was completing a manuscript for a new collection, Conversations at Midnight.

Their hotel burned down and the manuscript was destroyed. In 1936, she was involved in a car accident that left her in such chronic pain that she became dependent on painkillers.

She was crushed when Eugen Boissevain died suddenly in 1949. The next year, she sat alone in their home, Steepletop, with a bottle of wine at the top of a staircase. She tumbled down the stairs, broke her neck, and died. It has been speculated that this may have been precipitated by a heart attack.

Edna St. Vincent Millay was 58 years old and left a body of work that included some fifteen poetry collections, several plays, and many political writings.

. . . . . . . . . .

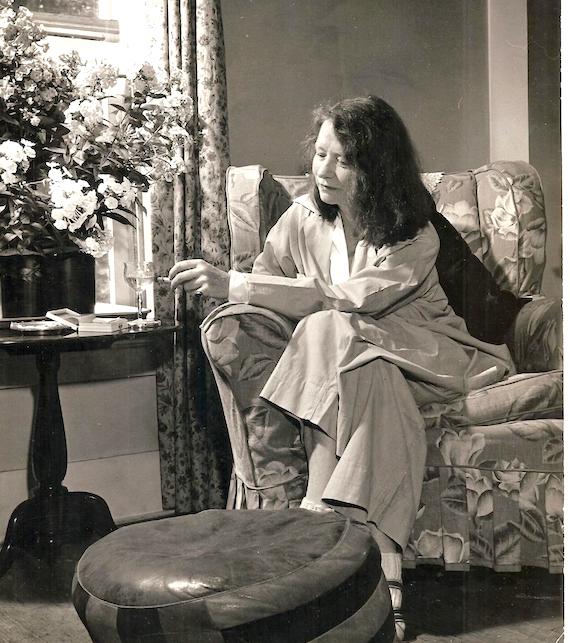

Edna St. Vincent Millay at home at Steepletop

. . . . . . . . . . .

A contemporary view of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s legacy

In Edna St. Vincent Millay: Selected Poems (Library of America, 2002), J.D. McClatchy (the volume’s editor), offered this assessment of her legacy, helping to understand why she’s no longer as widely read as she once was.

“If literary historians can agree on anything, it’s that the road to hell is often paved with good reviews. At the start of her career, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s reviews were astonishing. By 1912, when she was just eighteen, she was already famous. When, five years later, her first book appeared, she was launched on a rushing current of acclaim.”

And by the end of her life, good reviews, McClatchy concludes, were merely dutiful:

“Of all the critical barbs aimed at Millay’s poems over the years, few have not had real targets. Still, two dozen of her poems can stand among the best lyrics of the twentieth century, and all of her work urges rediscovery.

In a sense, it was her misfortune to write at a time when the tide had turned in favor of the modernists, who felt as T.S. Eliot did when he wrote that “no artist produces great art by a deliberate attempt to express his own personality.”

Millay wrote from the bedroom, not the library. Eliot and Pound were expansionists, broadly addressing themselves to culture and ideas. Millay, on the other hand, wrote of private life, domestic scenes …

After her death, fashions again changed. The confessional poets flayed the lyric to reveal garish details Millay’s decorum would have instinctively avoided. And all along, though she was never forgotten by poets (Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton studied her with admiration), critics eager to extol the skewed obliquities of the modernists or the “authenticity” of the plain-speaking nativists ignored Millay …

The neglect has kept us from a poet of genuine strength. Millay’s emotional range may seem narrow, and her technique often limited to exquisite feelings dipped in bitter irony …

And often because of these self-imposed restraints, Millay could write poems with an obsessed, haunting power — her sonnets especially, each a silver cage for the melancholy, winged god of love — poems that expose the banalities of more burly or experienced styles, and continue to touch the heart, disturb the intelligence, and lodge in the memory.”

. . . . . . . . .

Photo by Anna Fiore

. . . . . . . . .

A 2018 article in The Guardian argues for a reconsideration as well. “Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry has been eclipsed by her personal life — let’s change that” states:

“For far too long, Millay’s work has been overshadowed by her reputation. A party girl poet. A sexually adventurous bisexual. A morphine addict. But then Millay also won the Pulitzer for poetry in 1923; the following year, literary critic Harriet Monroe called Millay was “the greatest woman poet since Sappho.”

In a review of a 2001 Millay anthology, the Atlantic proclaimed that “the first rule of modern literary biography is that the life renders the work incidental” – but what happens when the life begins to obscure the richness of the work?

Focusing on Millay’s relationships with both men and women has been de rigueur for the last half century – so it is high time that her words were allowed the limelight again.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Steepletop and the Millay Colony

A number of years after her death, the state of New York acquired a great portion of the acreage of Steepletop, and the funds were used to establish The Millay Colony for the Arts. Today, this center offers residencies for writers and other creative artists.

Steepletop itself was established as a museum dedicated to Millay’s life and work, including garden trails and her gravesite. As of 2019, however, Steepletop has been closed to the public due to financial constraints.

More about Edna St. Vincent Millay

On this site

- Quotes by Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Renascence by Edna St. Vincent Millay (1912)

- 12 Iconic Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

- 13 Love Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

- The Friendship of Edna St. Vincent Millay and Elinor Wylie

- Rapture and Melancholy: The Diaries of Edna St. Vincent Millay (excerpt)

- How Losing a Poetry Competition Launched Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Career

Major Works – Poetry

Millay also wrote a number of short plays in addition to her poetry collections. Her full bibliography can be found here. There were a number of posthumous poetry collections published as well.

- Renascence: and Other Poems (1917) – full text

- A Few Figs from Thistles: Poems and Sonnets (1920, 1921) – full text

- Second April (1921) – full text

- The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver (1922) – full text

- The Buck in the Snow and Other Poems (1928)

- Fatal Interview (1931)

- Huntsman, What Quarry? (1939)

- Make Bright the Arrows: 1940 Notebook (1940)

- Mine the Harvest (1954)

Biographies and Letters

- Letters of Edna St. Vincent Millay, edited by Allan Ross Macdougall, Harper (1952)

- Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Nancy Milford (2001)

- What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay

by Daniel Mark Epstein (2002) - Rapture and Melancholy: The Diaries of Edna St. Vincent Millay, edited by Daniel Mark Epstein (2022)

More Information

- Poetry Foundation

- Poets.org

- Wikipedia

- Biography

- “Afternoon on a Hill” — a portrait of ESVM

- Reader discussion of Millay’s works on Goodreads

Leave a Reply