Flannery O’Connor, author of Southern Gothic fiction

By Nava Atlas | On December 25, 2018 | Updated March 27, 2023 | Comments (0)

Flannery O’Connor (March 25, 1925 – August 3, 1964) was born Mary Flannery O’Connor in Savannah, Georgia. She was best known for her short stories — morally driven narratives populated with flawed characters sometimes described as grotesque.

O’Connor was viewed as a bit different by her fellow townspeople in Milledgeville, Georgia. She stood apart from the itinerant farm workers and country folk, becoming something of an observer. There was nothing she ever wanted to do other than write.

You may notice that some of her book covers feature peacocks, which is a nod to the fact that she helped raise the beautiful birds on her family’s farm.

Flannery O’Connor biography highlights

- Flannery O’Connor got a running start to her writing career by attending the renowned writing program at the University of Iowa and a fellowship at the Yaddo residency.

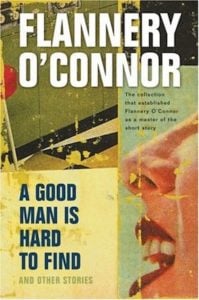

- Her first stories became part of the collection, A Good Man is Hard to Find (1955).

- While working on her first novel, Wise Blood, O’Connor was diagnosed with lupus, forcing her to move back to her home town of Milledgeville, Georgia, and live with her mother.

- Her work is filled with detail, symbolism, and religious imagery. It’s categorized as Southern Gothic with strains of the grotesque, and relies on regional themes. As a practicing Catholic, O’Connor’s faith imbued her work with a personal, sometimes peculiar vision.

- O’Connor was deeply immersed in the craft, writing and rewriting, and revealed much about her own writing life in essays. She considered writing a redemptive act.

- Flannery O’Connor was only 39 when she died in1964. In 1971, the posthumous Collected Stories won the National Book Award.

First novel and a diagnosis of lupus

Though quirky and anxious, O’Connor recognized her potential and hoped to fulfill it. In a diary entry written when she was eighteen and just starting college, she wrote:

“I AM. THIS IS NOT PURE CONCEIT. I am not self-satisfied but I feel that God has made my life empty in this respect so that I may fill it in some wonderful way—the word ‘wonderful’ frightens me. It may be anything but wonderful. I may grovel the rest of my life in a stew of effort, of misguided hope.”

After graduating from a woman’s college in Milledgeville, O’Connor attended the highly regarded writing program at the University of Iowa.

During a fellowship at Yaddo in 1948, the prestigious residency in Saratoga Springs (NY), she worked on the stories that would later make their way into A Good Man is Hard to Find (1955). The following year, 1949, she moved to New York City. At the age of 24, she was ready to begin her writing career in earnest.

While working on her first novel, Wise Blood, O’Connor was diagnosed with lupus, the rare autoimmune disorder from which her father had died. Soon after, she moved back to Milledgeville. There she stayed, living with her mother for the rest of her life. She helped her mother raise chickens and peacocks as she pursued her writing.

“I am going to be the World Authority on Peafowl, and hope to be offered a chair some day at the Chicken College,” she wrote with her characteristic dry wit to writer Robert Lowell.

For a time, costly steroid medications helped control her symptoms. Even while stricken with lupus, she wrote every day, producing a body of work that included two novels and more than thirty short stories.

. . . . . . . . .

Flannery O’Connor on the Grotesque in Fiction

. . . . . . . . .

Southern Gothic, the grotesque, and the role of religion

Today, her work is still much discussed because of its detail, symbolism, and religious imagery. Her work is categorized as Southern Gothic and relies heavily on regional themes. In this way, it bears a stylistic relationship to the writings of Carson McCullers and William Faulkner. As noted in Women of Words by Janet Bukovinsky Teacher (1992):

“These writers took their inspiration from the regional mysteries and peculiarities of the deep South — its characters, language, and ways of life.

Before a reading of her work, O’Connor once said, ‘I doubt if the texture of Southern life is any more grotesque than that of the rest of the nation, but it does seem evident that that the Southern writer is particularly adept at recognizing the grotesque.'”

O’Connor said: “Whenever I’m asked why Southern writers particularly have a penchant for writing about freaks, I say it is because we are still able to recognize one. To be able to recognize a freak, you have to have some conception of the whole man, and in the South the general conception of man is still, in the main, theological.”

She also famously said: “Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.” Though her themes were often serious and dark, her writing was imbued with wit.

O’Connor was Catholic, which set her apart in a region filled with Baptists and Protestants. Her faith imbued her work with a personal and sometimes peculiar vision. Wise Blood tells of a violent young religious extremist. Fanaticism is also at the heart of The Violent Bear it Away.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The art and craft of the writing life

O’Connor kept her private life to herself, but was outspoken on the art and craft of writing and the writing life. Some have said that a seething anger rises up from her stories. Wise Blood, The Violent Bear it Away, and her collection of stories, A Good Man is Hard to Find, were all praised by critics.

Although she lived a somewhat sheltered life, O’Connor’s work depicted subtleties of human behavior with razor precision. Her dark humor wasn’t appreciated by all — its religious overtones (she was a devout Catholic) were highly provocative. She was also an avid book reviewer, penning more than one hundred reviews for various publications.

Writing was almost a redemptive act. She said in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose (1970):

“I have found, in short, from reading my own writing, that my subject in fiction is the action of grace in territory largely held by the devil. I have also found that what I write is read by an audience which puts little stock either in grace or the devil. You discover your audience at the same time and in the same way that you discover your subject, but it is an added blow.”

O’Connor was asked why she wrote, and her answer was “Because I’m good at it.” It wasn’t a statement of ego, but one of fact. She was deeply immersed in the craft, writing and rewriting.

. . . . . . . . . .

Flannery O’Connor Quotes on Writing and Literature

. . . . . . . . . .

Later life and early death of Flannery O’Connor

Despite her illness — and the treatment for it, which also weakened her — O’Connor enjoyed traveling and giving talks, and continued to write. In 1964, she had surgery for a stomach disease, which exacerbated the lupus. She died on August 3 of that year. She was 39 years old.

In 1971, the posthumous Collected Stories won the National Book Award. One critic noted that she “did not live long, but she lived deeply, and wrote passionately.”

More about Flannery O’Connor

On this site

- “A Good Man is Hard to Find” — an analysis

- O’Connor on the Grotesque in Fiction

- Wise Quotes by Flannery O’Connor

- Flannery O’Connor quotes on writing and literature

- Dear Literary Ladies: How can I develop good writing habits?

- Dear Literary Ladies: Should I take time off work to write full time?

- Dear Literary Ladies: How much do authors want their work to be analyzed?

Major works (fiction)

- Wise Blood (novel, 1952)

- A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories (1955)

- The Violent Bear It Away (novel; 1960)

- Everything that Rises Must Converge (stories, 1965)

- The Complete Stories (1971, posthumous)

Major works (nonfiction, all posthumous)

- Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose (1970)

- The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor (1979)

- The Presence of Grace: and Other Book Reviews (1983)

Biographies & Criticism

- Flannery: A Life of Flannery O’Connor by Brad Gooch (2010)

- Flannery O’Connor: A Life by Jean W. Cash (2004)

- The Abbess of Andalusia: Flannery O’Connor’s Spiritual Journey by Lorraine V. Murray

- Conversations with Flannery O’Connor, edited by Rosemary M. Magee

More Information

- Andalusia Farm, Home of Flannery O’Connor

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion of Flannery O’Connor’s books on Goodreads

- What Flannery O’Connor’s College Diary Reveals

- How Racist was Flannery O’Connor?

Leave a Reply