The Excellent Marriage of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas

By Elodie Barnes | On November 13, 2020 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (8)

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, both Americans, met on September 8, 1907 as new expats in Paris. The two bonded immediately. They remained lifelong partners until Stein’s death, with Alice serving as the doting wife, and later, keeper of her legacy.

“I may say that only three times in my life have I met a genius and each time a bell within me rang and I was not mistaken…The three geniuses of whom I wish to speak are Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, and Alfred Whitehead.”

This is the meeting of Gertrude Stein (1874 – 1946) and Alice B. Toklas (1877 – 1967) as written in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933). It is Gertrude’s writing, Alice’s voice, and their meeting — twenty-five years previously — recounted as both of them wished to remember it.

Whether true or not, the gravitas of the moment seems fitting. It was, after all, the start of one of the longest and most stable marriages in the history of Modernist literature: a partnership that was often framed in terms of the writer and her muse, and yet was a true partnership built on interdependence and lasting love. For almost forty years, they were never apart.

The dynamics of their relationship, played out in Gertrude’s writing and in the literary and artistic milieu of inter-war Paris, fascinated their contemporaries. They still fascinate and inspire today.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas: An auspicious beginning

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas met in Paris in September 1907, when Gertrude was 34 and Alice 30. Gertrude was already a fixture of Left Bank Parisian life: terrifying some, exasperating others, inspiring many. She had become well known not only for her impenetrable writing, but for championing lesser-known artists and collecting their works.

Together with her brother Leo, with whom she had shared a pavilion and adjoining atelier at 27 rue de Fleurus, she had amassed a collection of works by the likes of Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso. As a consequence, the atelier had become ‘the’ place for artists to gather to meet each other, to talk, and to admire the paintings. Most of these visits were condensed into a Saturday evening — the famous Stein salon — but visitors were expected and (mostly) welcomed at all hours of the day.

Alice, however, had only just arrived in Paris. She had been persuaded into the trip by a friend, who thought she could do with a change from home life in San Francisco: Alice had been caring for her father and younger brother following her mother’s death.

She was a talented pianist who had been set on a promising concert career and, although she had abandoned her formal studies, her interest in the arts — in music, painting, theatre, and literature — remained unabated. She had also already met Gertrude’s brother and sister-in-law, Michael and Sarah Stein, who had visited San Francisco the previous year.

Just a few days after Alice’s arrival — perhaps out of curiosity, perhaps out of duty towards her brother’s friend — Gertrude called and invited her for a walk. Whatever her motives, the outing was a success. Alice later described the meeting in her own memoirs: “I was impressed with her presence and her wonderful eyes and beautiful voice — an incredibly beautiful voice … Her voice had the beauty of a singer’s voice when she spoke.”

With her short-cropped, iron-grey hair, sandals, and bulky frame clad in long robes, Gertrude was certainly an impressive figure. The contrast they must have presented walking the streets of Paris — for Alice was tiny, dark, mustached, and dressed in flower print dresses and elaborate earrings — must have been striking.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Rhythm and routine

The two women formed an intense attachment from the beginning. There were further walks around Paris: Gertrude enjoyed wandering the streets and both women loved to shop for clothes. Alice, in particular, was attracted to the new Paris fashions.

As they walked, they talked about Gertrude’s writing. She had just finished her novel Three Lives and was working on The Making of Americans, but was facing an increasing lack of support from her brother. Leo was her closest sibling, the one who had always been there for her and she for him, and yet they were drifting further and further apart. Gertrude needed encouragement and approval, which Alice was happy to provide.

By December 1908, Alice had assumed the roles of editor, typist, secretary, general sounding board, and personal assistant. Each morning she would go to the rue de Fleurus to type Gertrude’s growing manuscript — no easy feat given the illegibility of Gertrude’s handwriting, which even Gertrude herself often struggled to read.

Gertrude would get up around lunchtime, having been writing for most of the night, and she would take coffee with Alice while Alice ate lunch. Sometimes in the afternoons, Alice would return to her own apartment, nearby on the rue Notre Dame des Champs, but more often the two women would take a walk before returning to the rue de Fleurus.

They were not yet lovers, and each evening Alice would leave. Gertrude would then work through the night, a habit she had developed as visitors to see the artworks had become more common. It was, she claimed, only after 11 p.m. that she could be sure the doorbell would not ring.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Gertrice / Altrude

By the summer of 1910, Gertrude had “proposed” to Alice, and Alice had accepted. Alice moved into the rue de Fleurus in July and, shortly afterward, Leo Stein moved out. The difference in living arrangements led to a marked change in the style of Gertrude’s writing.

Alice’s roles as a sounding board and as capable editor (she was, by all accounts, more than willing to ask pointed questions and to engage in discussion over the finer points of structure and poetic nuance) gave Gertrude’s writing a second voice: this became more evident as time went on and Gertrude took Alice into her confidence more and more. In one of Gertrude’s notebooks, she even intermingles their names, coming up with ‘Gertrice / Altrude’.

Always, within all of her roles, Alice’s main focus was Gertrude, to attend to her needs and to make sure that she was heard. Gertrude acknowledged this devotion in her writing: in one of her first word portraits, Ada, she wrote, “Someone who was living was almost always listening. Someone who was loving was almost always listening…”

Their relationship also encouraged an exploration of sexuality. Their marriage was Gertrude’s primary inspiration, but she often described it in heterosexual terms with herself as “husband” and Alice as “wife.” Erotic and domestic lesbian themes were couched in cryptic language, perhaps to explore the limits of both the language itself and conventional gender roles, and perhaps to avoid the attention of the censor.

. . . . . . . . . .

Tender Buttons

. . . . . . . . . .

Tender Buttons

Tender Buttons, written in 1912, is perhaps the piece that most clearly shows the transition Gertrude was making in her work. The sexuality was clear even to those who didn’t know about her relationship with Alice: it was, according to Shari Benstock, a “grammar of lesbian domesticity.”

Later, in Didn’t Nelly and Lilly Love You (1922), Gertrude’s writing undertook a playful exploration of gender that was far more fluid than the roles she and Alice played out in their relationship. This story, of Gertrude and Alice’s birthplaces and their meeting in Paris, begins with the conventional “he” and “she” before morphing into the less clear-cut “we” and “I.”

The ambiguity was frustrating for many; having worked her way through Didn’t Nelly and Lilly Love You, Natalie Barney said tartly that she could never “make out whether they did or they didn’t — the chances being two against one they didn’t.”

A new kind of Stein salon

Both women were aware that, in America, they would not have been able to live out their relationship in nearly so much freedom as in Paris. Neither would Gertrude — cryptic language or not — have been able to explore it in her writing. However, they were still cautious about their choice of friends, and in the early years of their relationship privacy was important.

The famous Stein open house continued in a scaled-down form for several years, but by 1913 it was unrecognizable. Alice did not enjoy that form of entertaining and was never comfortable at large dinners and parties. She preferred smaller, more intimate gatherings, and gradually their social life adjusted.

Those who came to 27 rue de Fleurus on a Saturday now came by invitation only, singly or in pairs. They talked at length with Gertrude while Alice served cakes and tea, or elaborate dinners that she had prepared herself. If male visitors brought their wives, Alice took great pains to keep the women away from Gertrude, occupying them with talk of cooking and needlepoint while their husbands had the privilege of an audience with the writer herself.

Later, Janet Flanner — a regular attendee during the 1930s with her partner Solita Solano, said it was as if “Gertrude was giving the address and Alice was supplying the corrective footnotes.”

No one was allowed to intrude on Gertrude’s work, or to question the relationship of the two women too closely. Alice acted as a kind of indispensable gatekeeper, ensuring that Gertrude received the stimulus of company and conversation when she wanted it, and was left alone when she needed to be to write. It was a role that suited both of them.

. . . . . . . . . .

Alice and Gertrude with their beloved dog, Basket

. . . . . . . . .

“Auntie”

This rhythm, like everything, changed with the outbreak of war in 1914. Initially, Gertrude and Alice traveled to Mallorca to sit things out in relative safety. But when it became clear that things were not going to be over quickly, they returned to Paris and volunteered for war work with the American Fund for French Wounded.

They even acquired a car for the purpose, a battered old Ford from Gertrude’s cousin in America which, when repaired and declared roadworthy, was christened “Auntie” after Gertrude’s aunt Pauline who “always behaved admirably in emergencies and behaved fairly well most times if she was properly flattered.”

Always together, and always in Auntie, they spent the next years shuttling supplies and soldiers to and from lines and billets. Gertrude’s driving left something to be desired, however. They had their only real arguments over her inability to reverse.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Postwar Paris and artistic struggles

After the war, as American and British expatriates began to arrive in Paris in greater numbers, Gertrude found herself becoming something of a cult figure. Her work had been published in various of the little magazines, and her reputation was already legendary among the young writers and artists.

She and Alice began to be less restrictive in their social life: they frequented Shakespeare & Co., the new Anglo-American bookshop run by Sylvia Beach, and sometimes attended Natalie Barney’s Friday salons. New friends and old congregated in the winding Left Bank streets: Mabel Dodge, Mina Loy, Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, H.D. and Bryher, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap.

Despite this, they took care to avoid close friendships with women of the Paris lesbian communities. Neither had ever been particularly demonstrative in public, and both were keen to avoid the kind of gossip and scandal that followed Natalie Barney (whose antics often shocked Gertrude, despite their friendship and general support of each other’s work).

Instead, Gertrude created her own circle of followers through her salon, mostly young and ambitious men such as Ernest Hemingway and Thornton Wilder. She felt she had no need for any other women, even in friendship. Alice provided her with everything she needed, and their life together was, by 1920s standards, relatively quiet: a marriage based on fidelity, their beloved poodle Basket, and regular trips to their home in the country (by this time, “Auntie” had been replaced with “Godiva,” although Gertrude’s driving never improved).

Gertrude continued to write but had little luck with book-length publications. Correspondence with various publishers and editors reveals the extent to which they were confused by her work: one example was Frank Palmer, of Frank Palmer publisher in London, who wrote in 1913 to say that he had “to confess to being as stupid and as ignorant as all the other readers to whom the book has been submitted.”

While Gertrude remained outwardly undaunted, privately she was despairing. Although the rejections may have actually contributed to her reputation during the rebellious 1920s — when, Bryher claimed, any writer who sold a manuscript to an established publisher had to move across the river to the Right Bank for their own safety — she understandably wanted recognition and understanding of her work.

One of her biggest champions, William Carlos Williams, even wrote a “Manifesto” in defense of Gertrude’s writing. But it was Alice who, out of belief in Gertrude and probably more than a touch of frustration, established the Plain Edition Press in 1930 in order to privately publish Gertrude’s work. The venture was financed by the sale of a Picasso.

. . . . . . . . .

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

. . . . . . . . . .

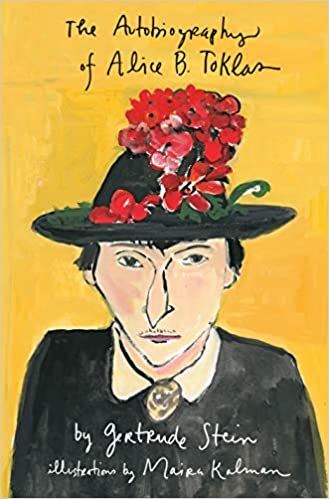

The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas

In 1933, the publication by The Bodley Head of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas marked a turning point in Gertrude’s life and career. She finally received her first book contract, and its success was such that a Pulitzer was predicted (although it never materialized).

The book was seen as a radical departure from the convention of biography, even though it was possibly the least radical of all of Gertrude’s recent writings, and its success also made Alice a household name. It is, perhaps, ironic that it was not Gertrude’s personal style which eventually brought her the recognition she so craved, but a work written in the ordinary, direct speaking voice of Alice Toklas.

In 1934 both Gertrude and Alice returned to America — the only time they did so — in order to promote The Autobiography. The press loved Gertrude and the book, although there was much debate about both Alice herself (the New York Post reported that, “…she brought with her Alice B. Toklas, her queer, birdlike shadow … her girl Friday talked about Miss Stein, when she talked at all …”) and Gertrude’s style of writing.

Most of the papers could not resist a parody of it, and the Detroit News announced that “A New York literary analyst professes to understand the poems of Gertrude Stein. It complicates the matter considerably, as we must now try to understand the analyst”

The Autobiography also had its detractors, mainly those who were portrayed in its pages and felt their depiction was unfair. A supplementary issue of transition magazine was published entitled ‘Testimony against Gertrude Stein’ to allow those people to have their say.

The World War II years

When war broke out again in 1939, there was no question of volunteering. Aged 66 and 63, and both of Jewish heritage, Gertrude and Alice retreated to their country home in the South, leaving the art collection stored under lock and key in their Parisian apartment.

In a later article for Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1940, Gertrude explained their decision to stay in France by saying that leaving would have been “awfully uncomfortable and I am fussy about my food.”

They managed to survive the hardships and rationing of the war years, supported by the villagers who kept their presence as Jews a secret. Some sources suggest that they were also helped by Gertrude’s friendship with Vichy government officer Bernard Faÿ.

It was certainly Faÿ’s influence that helped to save the art collection from Nazi looting while Paris was under occupation, and it was at Faÿ’s suggestion that Gertrude translated a selection of speeches by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Although destined for an American audience, these translations were never published.

The support for Pétain that Gertrude displayed in her introduction was unpalatable to American publishers, and in 1941 she stopped translating. Her main work from these years was Wars I Have Seen, a documentation of her observations and experiences throughout two world wars. It received mixed reviews, with many feeling that Gertrude’s political observations overreached her grasp and others denouncing her continued support for Pétain. In autumn 1944, they moved back to Paris.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Carrying on alone

Gertrude died of cancer on 27 July 1946. Alice was left to carry on alone, and the journey wasn’t an easy one. While their marriage had never been recognized in the eyes of either the law or society in general, Janet Flanner commented that Alice, in her grief, “was the most widowed woman I ever saw.”

Over the years, Alice’s practical situation became more and more precarious. In increasingly poor health and almost blind, she returned to Paris from Rome one summer in 1961 to find the walls of her apartment stripped bare: Gertrude’s collection of paintings had been impounded.

The artwork was supposed to have been insurance for Alice in her old age, with Gertrude’s will stipulating that certain of the works could be sold in order to pay for Alice’s upkeep as well as for the publication of Gertrude’s work.

However, members of the Stein family had taken an inventory of the collection while Alice was away, discovered that several Picasso drawings were missing (having been legitimately sold for the purposes of maintenance), and requisitioned the lot, claiming that Alice’s absence had invalidated the will and endangered the paintings.

The long absence from Paris had also left her facing eviction: her landlord sued, claiming that the property had effectively been left vacant. With the help of friends (including Janet Flanner, who highlighted Alice’s plight in one of her “Letters from Paris” for The New Yorker) Alice was able to find a new home. She was philosophical about the loss of the paintings, saying only that, “I am not unhappy about it. I can remember them better than I can see them now.”

Living alone, she was cared for by devoted friends who believed that she deserved all the little extravagances they could afford her (such as strawberries from Fauchon’s — Janet even kept an empty Fauchon box handy so that it could be refilled, when money was tight, with cheaper neighborhood fruits instead).

In 1965, increasingly frail, she underwent cataract surgery. The bills were largely paid for by Gertrude’s old friend Thornton Wilder, and Virgil Thomson also helped out, joking that Alice was determined to have the surgery so that she “could see Gertrude clearly when the time came.”

She also wrote several books of her own, including The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook in 1954, which combined recollections of her years with Gertrude with recipes and anecdotes about French cuisine (and famously included a recipe for hashish fudge), and her memoirs What Is Remembered.

Touchingly, her recollections end with Gertrude’s death, and with Gertrude’s famous last words: “What is the answer? I was silent, In that case, she said, what is the question?”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

Further reading

- The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein: Penguin Classics, 2001

- Women of the Left Bank, Shari Benstock: Virago, 1987

- Paris Was A Woman: Portraits from the Left Bank, Andrea Weiss: Counterpoint 1995

- Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice, Janet Malcolm: Yale University Press, 2007

- Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein & Company, James Mellow: Praeger Publishers, 1974

- Everybody Who Was Anybody: A Biography of Gertrude Stein, Janet Hobhouse: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1975

- Gertrude Stein in Words and Pictures: A Photobiography, Renate Stendhal (ed): Algonquin Books, 1989

So interesting. I’m always intrigued by the compromises people make for survival, e.g., Stein’s involvement with the Vichy government. As well as in the nature of love!

Lynne, I’ve often wished I had an “Alice B. Toklas,” but in my case it would have to be a man, and there aren’t many who would put their creative efforts and egos in service of a woman’s. Leonard Woolf was one rare instance — though I’m not in any way equating myself with Virginia Woolf! In any case, Gertrude and Alice were an intriguing pair, and their legend and legacy live on forever.

Je connaissais un peu l’oeuvre et la personnalité de G.Stein mais rien de sa compagne je ne savais pas qu’elle avait vécu avec une femme. Passionnante personnalité, G.Stein. on la voit dans le film de Woody Allen Midnight at Paris…merci pour cet article

Merci Pierre. Je comprends le français parce que je l’ai étudié au lycée. Pour les autres, je vais traduire:

Pierre wrote:

“I knew a little about G. Stein’s work and personality but nothing about her partner, I didn’t know she had lived with a woman. Fascinating personality, G. Stein. on the voice in Woody Allen’s film Midnight at Paris…thanks for this article.

Thank you for your writing, it answered questions I had.

I was watching “Tru Love” Gertrude and Alice Paris was mentioned so this is how I got to your writing. Thank you again.

I’ve not heard of this (series? movie?) and would love to know more, Roberta! In any case, I’m glad you enjoyed this post.

Very good summary of a terrific relationship. Here’s my version from my blog, “Such Friends”: suchfriends.wordpress.com/the-american-ex-patriates-in-paris/how-could-gertrude-stein-write-the-autobiography-of-alice-b-toklas-and-whats-with-those-brownies/

Thank you, Kathleen! Your article looks great. I love the story about the hashisch brownies!