Natalie Clifford Barney, Avant Garde Poet & Novelist

By Elodie Barnes | On August 2, 2019 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (2)

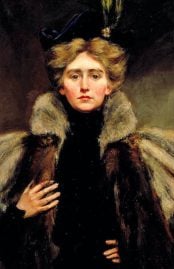

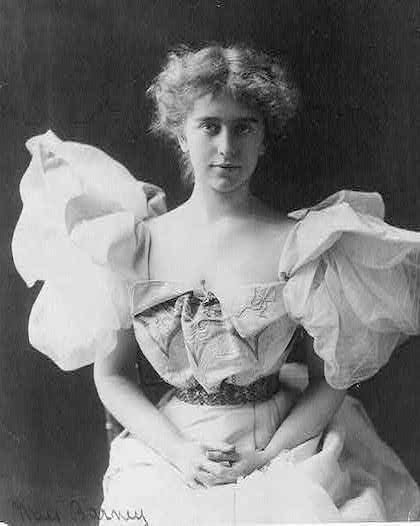

Natalie Clifford Barney (October 31, 1876 – February 2, 1972) was an American-born writer of poems, epigrams, pensées, and novels.

She made her home in Paris, where she was known more for her literary salon and her colorful personal life than her writing, despite publishing ten critically acclaimed books in her lifetime.

Natalie was “the wild girl of Cincinnati,” the grande dame of the literary salon and Parisian lesbian circles, and used her considerable wealth and influence to promote talented writers and artists from around the world.

Early years and education

Natalie was born to privilege. Her parents, Alice Pike Barney and Albert Clifford Barney, were wealthy through a combination of inheritance and private income, and the family had homes in Cincinnati, Ohio; Washington, DC; and Bar Harbor, Maine.

Natalie grew into a confident child, sociable and outgoing, and was naturally athletic with a particular love for riding horses. She was also beautiful, with a mass of pale blond hair that was often likened to moonbeams, sharp blue eyes, and delicate features.

The family often traveled, and from 1888 Natalie attended the exclusive Les Ruches boarding school in France. She was a good student, but later spurned the option of going to college, stating that she preferred education of her own design. She continued to study French, Greek, violin, and literature, seeking out informal and formal tutors who encouraged her ambitions.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Settling in Paris, beginning to write

In 1896 she left America to settle in Paris permanently. Writing and socializing were Natalie’s focus during the first years of the new century. She was drawn to shorter forms of writing, particularly poetry and pensées (literally “thoughts” or “fragments”), and always wrote in French, claiming that it was the language in which she could best express her emotion.

Her earlier works are full of love and loss and classical beauty, mostly inspired by her readings of the classical poets — Sappho was a favorite — and her own, already tumultuous, love life.

By 1910 she had published four books: Quelques Portraits – Sonnets de Femmes, Éparpillements, Je Me Souviens, and Actes et Entr’actes. All were published to critical acclaim.

Love poems to women

However, it was Quelques portraits – sonnets de femmes, a chapbook of love poems to women published in 1900, that garnered the most attention. Reviews ranged from mildly complimentary to gushing (Henri Pene du Bois wrote of Natalie’s “miraculous power to write French verse”), but the fact that they were essentially love letters to women caused great scandal in some circles.

Natalie’s father Albert, incensed by a headline that read “Sappho Sings In Washington,” stormed into the publisher’s offices to buy and then destroy the remaining copies and all printing plates. Consequently, the book is incredibly rare today.

Natalie became well-established in the glittering literary and artistic community of the Belle Epoque, and counted Colette, Pierre Loüys, Count Robert de Montesquiou, Lord Alfred Douglas, Jules Cambon, and Remy de Gourmont among her friends.

De Gourmont in particular was a lifelong admirer and promoter of her work. It was he who christened Natalie “The Amazon,” a nickname that would stick. She also continued to write, and Poems & Poèmes: Autres Alliances and Pensées d’une Amazone was published in 1920.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Years of the salon

Natalie, perhaps taking after her mother, was a natural hostess. She was sociable, lively, and sharply witty. She also knew how to make people feel at ease, when to relinquish the spotlight, and how to promote others.

It was this perfect combination of talents — as well as her own artistic and literary accomplishments — that made her Friday literary salon into arguably the most famous in Paris. It began when she moved into a pavillon at 20 rue Jacob, in the heart of the Left Bank, in 1908, but its heyday was the 1920s.

During these years, Friday afternoons were filled with writers and artists from all over the world. They came for the chance to mingle, to introduce and be introduced, to promote their work and hear the work of others, and to eat the famous chocolate cake.

Regular attendees included Colette, Djuna Barnes, Ford Madox Ford, Paul Valéry, Ezra Pound, Mina Loy, and André Germain. Others such as Rilke, T.S. Eliot, Nancy Cunard, Somerset Maugham and Peggy Guggenheim dropped in occasionally.

There were definite standards for admission. Intelligence, artistic accomplishment, celebrity, and, in the case of women, beauty and style — any or all of the above were prerequisites for an invitation. Once there, however, the salon was noted for its inclusivity. Natalie was tolerant and open-minded, and people of all nationalities, religions, and sexual persuasions were welcome.

Natalie used the salon as a way of assisting those who were struggling financially, and she gave generously to individuals who she felt were worthy of her input. She also promoted tirelessly, particularly the work of women which, at the time, was generally not taken as seriously.

Her 1927 Académie des Femmes was a response to the all-male bastion of the Académie Française, and harked back to an earlier ambition of establishing a community of women poets on the island of Lesbos. Women writers were honored with their own Friday at the salon, during which they would read from unpublished works or works in progress.

The Académie included Colette, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, Mina Loy, Elisabeth de Gramont and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus. Although it faded away after 1927, it remained one of Natalie’s greatest achievements.

The salon ran — with a break over the years of the Second World War — almost until Natalie’s death, and was probably her most lasting and best known legacy.

Love affairs as inspiration

Natalie was known for being a lesbian. Even in Paris, where attitudes were relatively tolerant for the time, her complex love life and her refusal to hide it brought her even more attention than the salon, and certainly more than her writing. Her approach can be summed up in her own words: “I am a lesbian. One need not hide it, or boast of it.”

She was also never monogamous, and her long term relationships — first with the poet Renée Vivien, and later with the artist Romaine Brooks and Elisabeth (Lily) de Gramont — were conducted against a continual backdrop of affairs, some more serious than others.

Natalie was as steadfast in friendship as she could be fickle in love, once claiming to be a lazy friend because “once I confer friendship, I never take it back.” Many lovers became close friends — close enough to immortalize Natalie in their works without offense being taken.

Natalie could be clearly seen as the main character in books by Liane de Pougy (Idylle Saphique), Djuna Barnes (Ladies’ Almanack) and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus (L’Ange et les Pervers).

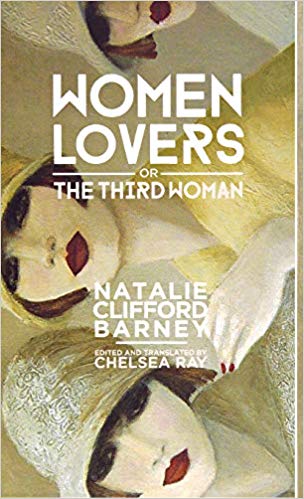

Many of Natalie’s own works were based on her love affairs and friendships, including Aventures de l’Esprit (published in 1929 and containing reflections on her salon friendships) and the astonishing novel Amants Féminins ou les Troisième (translated into English by Chelsea Ray as Women Lovers or the Third Woman, an account of a three-way relationship with Liane de Pougy and Mimi Franchetti that ended in heartbreak for Natalie).

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Later years of Natalie Clifford Barney

In the years immediately preceding the war, Natalie continued to write and publish her own work, run the salon, and socialize. She also traveled widely, settling into a seasonal routine of spending the winter with Romaine on the Côte d’Azure, the autumn in Romaine’s home above Florence, and taking trips to spas in France and Switzerland in between with Lily.

In 1930, her novel The One Who Is Legion was published — a strange, surreal account of a person who, having committed suicide, is brought back to life as a genderless being with no memory. Natalie herself claimed that it came from “the several selves … their conflicts and harmonies” that she felt she possessed. It was the only work that she published in English.

Natalie saw out the war in Florence with Romaine, and did not return to Paris until 1946. The house at rue Jacob was uninhabitable, and it was a further three years before she could move back in and recommence the Friday salons.

Other post-war projects included reestablishing the Prix Renée Vivien for women poets writing in French; and the private funding of three books which commemorated Dolly Wilde and Lucie Delarue-Mardrus. She also started work on her memoirs, which would later be published in 1960 as Souvenirs Indiscrets.

The amazon’s last Friday

Natalie never stopped writing, and her last book, Traits et Portraits, was published in 1963 when she was eighty-six. Her personal life, too, was no less vibrant.

Her long relationship with Romaine finally ended when both were almost 90, at which time Natalie met and fell in love with the much younger Janine Lahovary. Janine would be Natalie’s last love and also her carer in her final years, but the split with Romaine — who Natalie thought of as the love of her life — devastated Natalie.

She also endured the loss of the house at rue Jacob, having rented it for almost 60 years, when it was suddenly bought and an eviction notice served. Natalie spent her last months in the Hôtel Meurice, overlooking the Tuileries Gardens, increasingly infirm with the effects of old age. She died in February 1972 — on a Friday — at age ninety-five, and was buried in Passy Cemetery in Paris.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Natalie Clifford Barney

Major works

Most of Natalie Barney’s major works were originally published in French:

- Quelques Portraits-Sonnets de Femmes (1900)

- Cinq Petits Dialogues Grecs (1901)

- Actes et entr’actes (1910)

- Je me souviens (1910)

- Eparpillements (1910)

- Pensées d’une Amazone (1920)

- Aventures de l’Esprit (1929)

- Nouvelles Pensées de l’Amazone (1939)

- Souvenirs Indiscrets (1960)

- Traits et Portraits (1963)

- Amants féminins ou la troisième (2013)

English translations

- Women Lovers, or the Third Woman

- A Perilous Adventure: The Best of Natalie Clifford Barney

Biographies

- Adventures of the Mind: The Memoirs of Natalie Clifford Barney (1992)

- Wild Heart, A Life by Suzanne Rodriguez (2003)

More information

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Natalie Clifford Barney: Queen of the Paris Lesbians

- Barney’s setting in Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party

- A Natalie Barney Garland on the Paris Review

The picture at the very beginning of this article is of Romaine Brooks, not Natalie Barney.

Oh my gosh, you’re right … it has been corrected. Not sure how that happened!