The Daring Fiction of Maude Hutchins

By Francis Booth | On January 3, 2022 | Updated July 19, 2024 | Comments (4)

Maude Phelps McVeigh Hutchins (1899 –1991) was raised in an upper-class environment, born to wealthy parents in New York City. She was orphaned at a young age and brought up by her grandparents, prominent members Long Island society.

This introduction to Maude Hutchins’ creative life, first in the visual arts and then more predominantly as the author of fiction considered daring even by mid-twentieth-century standards, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

A 1935 article about Hutchins (in her then role as a sculptor in Chicago) makes it clear just how aristocratic her family was. “Mrs. Hutchins’ mother was a Phelps, of a New England family that made their advent in Massachusetts in 1632. It was her Phelps grandparents who brought her up after her parents died.”

What upper class women could and couldn’t do

Women of Hutchins’ class had to contend with expectations as to what they could and couldn’t do, though being artistic wasn’t necessarily a problem. Critic Maxwell Geismar, in his 1962 introduction to Hutchins’ collection of stories The Elevator, called her “this country-bred, inherently ‘upper-class,’ and offbeat virtuoso (for Maude Hutchins is certainly that; while like most native aristocrats, she is profoundly democratic in her instincts).” Further:

It was nice for young ladies of fashion in her girlhood circles on Long Island to paint and draw. So Maude Phelps Hutchins had no traditional background of stern family objections thrown into her way of following her instincts to be an artist. Painting or drawing was one of the “accomplishments,” like playing the piano and doing needlework (as distinguished from sewing).

Her only problem when trying to be taken seriously as an artist was ‘the suspicion of being a dilettante,’ even though she did have an art degree from Yale University. But even there, women were treated differently. The main focus of the degree course was to get students on the Prix de Rome, but women were not allowed to apply for that so “the girls are allowed to develop pretty much as they please.”

The back cover blurb for Hutchins’ penultimate novel, Blood on the Doves, 1965 – an untypical, multi-voiced, Faulkneresque narrative – describes her background very nicely, underneath a photograph of Hutchins smiling broadly, sitting at the controls of the plane that she flew solo across America and looking nowhere near her age, which was then sixty-six. The logo on the side of the plane reads Super Cat, perhaps appropriately.

Although Maude Hutchins was born in New York and brought up on Long Island, she is half Virginian and half New Englander. Tutored, as she says, by a Connecticut Yankee, her grandfather, and a Virginian great aunt, she realized early that “I was always wrong.” This bringing up accounted also for her formal education ending at sixteen (grandfather said ladies do not go to college), and for her matriculation in the Yale School of Fine Arts after her marriage.

She received a B.F.A. from Yale University, but “piling clay on an armature in the basement of that University was not exactly an intellectual pursuit. I learned how to read, however,” she adds, “and had read most of ‘The Great Books’ before that term was invented.” She also learned to fly, and pilots her own plane.

. . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom is available on Amazon US and Amazon UK

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Women artists are barely respectable, writers are trouble

For Hutchins’ family, being an artist was just about respectable – though she did cause a stir in Chicago by exhibiting life-size nude male statues – being a writer was something else.

Long before she thought about writing novels Hutchins collaborated on an illustrated 1932 book called Diagrammatics, for which she provided lightly erotic, neoclassical line drawings of young, nude women – they are rather like more minimal versions of Picasso’s Vollard Suite, the first of which appeared in 1930 or his illustrations for Ovid’s Metamorphoses, published in 1931.

They also resemble the erotic, Beardsleyesque illustrations of young girls that Willy Pogány, by then a well-known illustrator and set designer living in New York, provided for a 1926 English-language translation of Pierre Louÿs’ Songs of Bilitis, which Louÿs had originally claimed were his French translations of Greek manuscripts from the same era and sexual orientation as Sappho.

It seems that Hutchins herself initiated this project and, not yet herself a writer, asked Mortimer J. Adler, a professor from Chicago University, of which her husband was then president, to write the words. Adler provided a truly terrible sub-Gertrude Stein text; it is not obvious whether the text is a spoof and the whole thing was a joke. The volume was privately published in a luxurious, limited edition. Although it was not widely distributed, Hutchins’ family was not amused.

“When I was fourteen and visiting a great-aunt, I was late to luncheon,” Mrs. Hutchins relates, “and I said, ‘But I beat Sylvia at tennis.’ My aunt looked at me coldly and said, ‘We have never had an athlete in the family before.’ Three years ago, I sent a copy of Diagrammatics to an elderly cousin. In a letter to me, he said, ‘We have never had an author in the family before.’”

Much worse, from her family’s, and her then ex-husband’s point of view, was to come when she started to write novels; though Hutchins did not publish anything until after her divorce, she wrote under her married name. Hutchins’ first novel was published in 1948, when she was forty-nine, the age Shirley Jackson was when she died.

The respective ages of their daughters when they were writing their novels may partly explain why Shirley Jackson’s teenagers are almost entirely sex-free – except Natalie Waite of Hangsaman (1951), whose one experience of sex is so awful she erases it from her mind and Jackson erases it from the novel – while Hutchins’ teen girls embrace sex and sensuality with great joy and a total lack of inhibition.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A creative woman overshadowed

Despite the aloof toughness her upbringing had given her, Hutchins is an example of a creative woman overshadowed – temporarily at least – by a dominant, alpha male. In 1921 she had married Robert Maynard Hutchins, who was to become the youngest dean of Yale Law School and then the youngest president of the University of Chicago. He was called Golden Boy even at the time.

Maude already had a moderately successful career as an artist and sculptor and was a rather glamorous figure: beautiful and striking, she was almost as tall as him. They were a golden couple and were compared to Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald; later they might have been compared to JFK and Jackie: it was at one time assumed that Robert Hutchins would either end up in the Supreme Court or running for president, though he did neither, partly at least because of the “trouble” he had with his wife.

In a memoir about Robert Hutchins, his former colleague Milton Mayer called Maude the “multifariously talented daughter of the editor of the New York Sun,” and said of her that, “her schooling was fashionable and her artistic talents were encouraged. She meant to have her own career – not her husband’s – and she had it. If he was shy, or stand-offish, she was genuinely aloof. She wasn’t meant to be a schoolteacher’s wife. (Perhaps she wasn’t meant to be anyone’s wife.)”

Scandalous stories

In a story published long after their divorce, “The Man Next Door,” published in her story collection The Elevator (1962), Hutchins writes a description of a man who seems to be a dead ringer for her ex-husband; it is by no means an unkind or unflattering portrait.

I am a country girl born and bred but my husband lives and thinks in a tiny city that he carries around inside his head. His handsome skull encloses very tall buildings and subways and elevators, and the buildings and subways and elevators are full of tiny cell-like people, each with his franchise, his exemption, and his problem. My husband is emperor, prince, chancellor, and his influence is like the handwriting on the wall.

In another story, Innocents,” in Love is a Pie (1952), a collection of stories and playlets (for which Andy Warhol designed multiple covers), Hutchins describes the relationship of a nameless couple that might possibly be a portrait of herself and Bob.

His outbursts of anger against her, which she feared, but which she preserved her strength for and which she made every effort to meet with the community, failing always, with the only “conclusions” he ever made. She was always fresh and he was always fatigued because it was her idea, not his; she was the artist. Unrequited love only comes to those who want it and even then it is not simple.

Artistic, creative, offbeat Maude never fit into her husband’s stuffy social milieu and caused him endless headaches. To “keep Maude quiet” and keep her busy, “poor old Bob” encouraged his wealthy friends to commission sculpted heads and busts from her – for enormous fees which many of his friends seriously resented – but this was never enough.

Maude scandalously paid undergraduates from her husband’s university, male and female, to model nude for her. She also produced family Christmas cards based on her own mildly erotic drawings that were sent to faculty and trustees; as one friend of Bob’s said about them in a memoir:

On at least one occasion with the nude figure of a going-on nubile girl holding a Christmas candle – the model was sensationally reported around town and gown to be the Hutchinses’ fourteen-year-old daughter Franja.

Thriving as a single independent woman

In the end, Bob got tired of keeping Maude quiet; after twenty-seven years of marriage, he left her in 1948 and she divorced him. He never spoke to her again. Within a year he had married his secretary; worse still, she was called Vesta – for a wife to be left for a secretary twenty years younger and even considerably shorter than herself is one thing, but if the other woman is called Vesta the horror is unimaginable.

Maude moved with her two younger daughters to the backwaters of Southport, Connecticut and stayed there, never remarrying and never – at least publicly – having any other serious relationship with a man; despite their differences, Bob must have been a tough act for any man to follow. And Maude didn’t need to work: Bob, whose salary was $25,000 a year, paid her $18,000.

Still, Maude was something of an alpha female herself, and thrived as an independent woman: she soon got her pilot’s license, as we have seen. Being left without a husband also seems to have encouraged Maude to write novels rather than concentrating on her visual art. She published nine novels between 1948 (the year of her divorce, so she must have been writing while she was still married) and 1967, plus two collections of her short stories, many of which had been published in leading magazines and printed in anthologies, including New Directions.

None of her publications were the kind of thing that the wife – even the ex-wife – of a highly respected member of Chicago society would be expected to produce, and she probably delighted in that fact.

Robert Hutchins published around twenty books of educational and political theory from 1936, when he was thirty-seven, to 1972, but, as mentioned earlier, Maude Hutchins was forty-nine when her first novel was published. She was sixty years old in 1959 when Victorine was released, and sixty-eight when her final novel was published.

The critics are shocked (or at least, uncomfortable)

Older women writing about sex makes middle-aged, male critics squirm; as we shall see, Hutchins suffered at their hands for daring to suggest that the mature woman – indeed any woman – might have lascivious thoughts. The New York Times said of her, “the sensuous is her window on the world; sexuality is the sea for all her voyages.”

Unlike Anaïs Nin’s work, most critics saw the sexual rather than the sensual; there was far too much sex in Hutchins’ novels for many people. At this time censorship was still very much the norm: Hutchins’ second novel, A Diary of Love was nearly prosecuted for obscenity; even the title seems designed to upset the prurient.

Some of Hutchins’ novels were, indeed, republished with sleazy, pulp-fiction covers: A Diary of Love was issued in at least three different pulp covers, all of which had above the title the teaser: “the sexual awakening of a teen-age girl.” At the bottom of the book’s cover, readers were assured that this was “complete and unabridged” — it had been previously issued in a censored version.

. . . . . . . . . . .

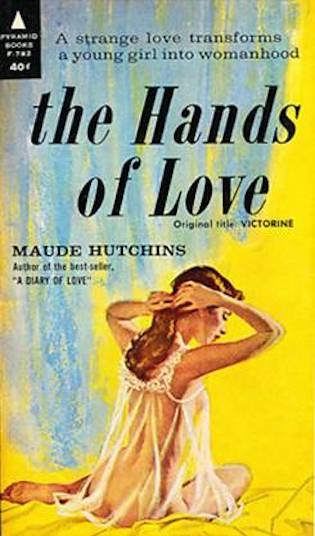

The Hands of Love (formerly titled Victorine)

. . . . . . . . . . .

Victorine was reissued as The Hands of Love, with the blurb, “a strange love transforms a young girl into womanhood,” and Maisie was issued by the Paris-based, erotic-novel specialist Olympia Press with the quote “the shockeroo of the literary season.” The cover featured a woman in bed who looked like she might be a prostitute in the saloon of a Western movie.

“Poor Bob” must have felt each of these as an arrow in the back; her family was likely not amused either. Maude could have used a pseudonym, but where would have been the fun in that?

These trashy covers and blurbs are entirely misleading and readers would have been seriously disappointed. It is not obvious whether she approved the lurid covers for these reprints of her books – as we saw with the now-classic lesbian pulp novels, authors at that time had little to no control over titles and covers – though Maxwell Geismar implies that she would not have:

Mrs. Hutchins would resent, I know, any description of her work as “erotic.” The curious thing about her writing, so remarkably open about all forms of personal behavior, was the prevailing tone of candor. If nothing human was foreign to her, everything human was a constant source of delight, of pleasure and gaiety.

When her book was banned by those sagacious guardians of the public morals, the Chicago police, Mrs. Hutchins was quite naturally bewildered.

“I can assure you that I have no desire to shock, disrupt the morals or undermine the conventions of the general public,” she wrote at the time. “My defense for A Diary of Love is that having written it, I published it; and that I would not willingly withdraw any of it. My intention was purely artistic, and the subject matter innocence.”

Yet some of Hutchins’ books are still in the list of the prestigious literary house New Directions with far more sober covers, though A Diary of Love has a very slightly naughty line drawing by Hutchins and Love is a Pie still has its original 1952 Andy Warhol line drawing of a woman as a cover. Surely no twentieth-century writer except Nabokov has been represented by such a range of cover art.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Victorine has even been reissued recently as a New York Review of Books Classic, part of an eclectic list that ranges from Balzac to Leonora Carrington, and includes Colette‘s The Pure and the Impure.

Hutchins is now becoming part of the American literary canon and moving slowly out of the ghetto of sex-obsessed writers, where she had been closeted, but the critics of the time were generally not kind to her, variously accusing her of being too experimental/literary on the one hand and of being too raunchy on the other.

A review of the short story collection Love is a Pie in the Saturday Review, for January 3, 1953, took the former line.

The stories, written in a prolix and often impenetrable prose, have the self-conscious literary stamp of the little magazines which first published several of them… For a book devoted to the tender human emotion, Love is a Pie seems curiously aloof and unemotional. It consists largely of strained and wearisome cerebral exercises.

Nine years later, a review of Honey on the Moon in the same magazine for February 29, 1964, slung at her the second kind of criticism.

According to all traditional criteria, the book is almost a complete failure. It has no core of moral significance; it takes place in no recognizable social context; most of the characters never come alive, and ninety percent of Mrs. Hutchins’s dialogue could never have been spoken by a human being.

But, although she never distinguishes between love and love-making, Hutchins writes about pure, animal sex with a genuine lyrical passion unmatched by any other contemporary American woman. And the blurry, schizoid interior monologues are almost as good – and hard to read – as those in Tender Is the Night.

If you are willing to endure a banal, pointless novel just for a few first-rate passages of good old you-know-what and a brief close-up of a personality tearing itself apart, you will like Honey on the Moon.

Even as late as 1964, critic Stanley Kaufmann was advising the then-sixty-five-year-old Hutchins to grow up and stop being so obsessed with sex; male critics have always tended to treat female novelists like naughty children – perhaps Hutchins was old enough to be his mother, and perhaps that was his problem with her. Male novelists, of course, never grow up and are allowed, even expected, to hang on to their obsession with sex their whole life.

Many novelists pass through such a period, but there comes a time when ‘then they went to bed’ suffices; or when the bed is to society what war was to von Clausewitz, a continuation of politics by other means. To remain as interested in sex as Colette was all her life long, and as Mrs. Hutchins continues to be, requires an almost monastic single-mindedness.

To be compared with Colette may be considered no insult: Anaïs Nin certainly meant it as a compliment; Colette wrote a series of novels that show the coming of age of her heroine Claudine, begun in 1900 with Claudine at School. Hutchins and Colette are probably the best exemplars of Nin’s ideal of an author who can write erotically without having any – or at least not very much – actual sex in her work.

The Memoirs of Maisie is a good example: despite the lurid picture on the cover of the pulp edition, which misleadingly shows a woman lying seductively on a bed in her underwear and despite the “shockeroo” quote in the blurb, Maisie is a grandmother on the verge of dementia, surrounded by her daughters and granddaughters (men are rarely at the center of Hutchins’ novels and here, they’re pushed way out to the periphery).

Maisie does however have reveries of her younger, passionate self, almost like an older Molly Bloom.

The nearest Maisie gets to a sex scene is written erotically, but no actual sex happens – because of the man’s temporary impotence. Colin and Sissy are both married, but not to each other; she agrees to meet him. Colin returns to his wife, knowing that he “had been fooled. He felt as if he had been lifted out of a magician’s hat by the ears and exposed to ridicule, wet and slinky, pink-eyed rabbit.”

Some of the short stories collected in Hutchins’ The Elevator also contain wonderful examples of erotic but sex-free writing. Hutchins can even make a description of a bride’s bouquet at her wedding crackle with an erotic charge. This is from ‘The Wedding,’ also in The Elevator.

The bride looked at the bouquet and saw that it was beginning to droop. One of the topaz roses turned brown, Violette began to shrink and a pink carnation trembled as if in a convulsion. A number of petals detached themselves and floated aimlessly in the still air and a hatch of yellow pollen, riding some tiny updraft, shone like powdered gold. She felt the stems grow feverish and then cold.

A pair of stamens detached themselves and floated downward, a pistil was bathed in perspiration, and the Shasta daisies, as if they were guillotined, lost their heads. She felt what remained of the bouquet struggling to be free of her hands, the flowers were delirious and the pulses in her own wrists began to beat like drums.

In The Future of the Novel, Nin points out perceptively that Hutchins tended to center her works around and see the world through the eyes of young people, especially adolescent girls, who are set against their awful parents while we see them coming of age:

Some of her parents resemble the parents of Cocteau’s Les parents terrible. It is the adolescents in her book who carry the burden of clairvoyance. They see, they know. It is not a battle between innocence and evil but between awareness and hypocrisy. Her adults are hypocritical. The novels are requests for truth, and this truth is usually uttered by those at the beginning of their lives. The work is unique, rich, animated by a sprightly intelligence and verve.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

The picture labeled “Maude and Robert Hutchins” is actually Vesta and Robert Hutchins.

Thank you for catching that, Steve — I’ve removed it.

This is a picture of Maude and Robert Hutchins. She was a striking beauty and they made a handsome couple. I wish I had made the effort to meet her.

https://storage.lib.uchicago.edu/ucpa/series1/derivatives_series1/apf1-05012r.jpg

That’s an amazing photo, Steve; do you think I’d be able to use it?