Leonora Carrington, Surrealist Artist and Writer

By Elodie Barnes | On September 25, 2021 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (0)

Leonora Carrington (April 6, 1917 – May 25, 2011, born Mary Leonora Carrington) was a British-born artist and writer who lived much of her life in Mexico City.

Best known for her surrealist paintings and artwork, and her prominence in the Surrealist group of the 1930s, she was also an accomplished author who published short stories, a memoir, and a novel.

One of Leonora’s recent biographers, Joanna Moorhead (also a distant relative on Leonora’s mother’s side of the family), wrote: “The key to Leonora was that she was a rebel, and a rebel to the very core of her being.” Even in early childhood, Leonora did not conform.

Her father, Harold, was a successful textile mill owner in Lancashire, England, and ran the company Carrington and Dewhurst. Her mother, Maurie, came from an Irish family and married Harold in 1908. They lived in luxury in Hazelwood Hall, a beautiful Victorian mansion near Morecombe Bay, where Maurie established herself as a society woman. It was these social norms and expectations, and the luxury of her upbringing, that Leonora railed against.

Her three brothers — Pat, Gerard, and Arthur — were sent to school at around seven or eight, but Leonora was kept at home under the tutelage of a French governess.

When she did finally attend a convent school, St. Mary’s Ascot, she was promptly expelled by the nuns, who wrote to her parents that, “This girl will collaborate with neither work nor play.” Her family nickname, Prim, was beginning to seem inappropriate.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Debutante

After a succession of schools and home tutoring, in which the main education was languages and the arts, Leonora was presented as a debutante at Buckingham Palace in 1935. The ritual was in its last years: by the end of the decade, King Edward VIII would substantially reduce the numbers of young women who were presented each year at the Palace, and cut back on the ceremony surrounding the tradition.

But for Leonora and the thousands of other young women presented in the same year, it was still in full swing and was the main event of the upper-class social calendar. Leonora, not a fan of balls and parties, was appalled and humiliated by the rigamarole. Later, she would remember the occasion as one that caused actual physical pain: “I was wearing a tiara, and it was biting into my skull.”

She drew on her experiences, and her savage opinions of her family’s money and social standing, to create one of her most gruesome and satirical short stories, “The Debutante.” In the story, a young woman befriends a hyena at the zoo before persuading it to take her place at a coming-out ball. The hyena attends wearing the face of the girl’s maid, which it had killed and eaten earlier in the evening, before jumping out of the window and making its escape.

Art school and surrealism

Leonora had long loved painting and drawing, and was determined to have some formal tuition. In 1936, her mother persuaded her father that the Chelsea School of Art in London would be a respectable enough choice: Leonora could stay with friends who would keep an eye on her, and it would keep her out of trouble for a short while at least.

Leonora did not stay long at the Chelsea School, moving to the Ozenfant Academy of Fine Art, run by Amádée Ozenfant and Ursula Goldfinger, just a few months after arriving in London. Leonora later remembered Ozenfant as an exacting teacher, making his students spend an entire term drawing just one object — an apple.

But it was there that Leonora was properly introduced to Surrealism, a way of looking at the world that chimed with her own. Later, as she explored further, Surrealism would allow her the freedom to explore her fascination with magical realism and alchemy, her obsession with animals, and the distinctions (or lack of them) between human and animal and machine, not only in her painting but in her writing too.

In the short story “As They Rode Along The Edge,” for example, written in the late 1930s, the main character Virginia Fur is something of a hybrid, caught between cat and woman with “bats and moths imprisoned” in her hair. In a lot of Leonora’s fiction, an ordinary human appears like an aberration.

For the time being, though, she was still experimenting and making the most of being in London with all its galleries, museums, and nightlife. Ozenfant would almost certainly have encouraged her to visit the first International Surrealist Exhibition, held in the early summer of 1936 at the New Burlington Galleries.

Artists with work on display included Salvador Dalí, Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Klee, Man Ray, Roland Penrose, Francis Picabia, Meret Oppenheim, and — fatefully — Max Ernst.

. . . . . . . . . .

Leonora with Max Ernst

. . . . . . . . . .

Bride of the Wind and Loplop

Leonora first met Max at a house party given by the Goldfingers. There has been speculation as to whether the couple was set up by Ursula and her husband Erno, or whether it was Leonora who engineered it, already infatuated with Max’s paintings from the exhibition before she had even seen the man.

Ultimately, though, it didn’t matter. Decades later, Leonora still remembered their meeting: they stood facing one another, having just been introduced, but the champagne had been poured too quickly and the glasses in their hands were about to bubble over. Max looked at Leonora before dipping his finger into his overflowing glass, and Leonora copied his movements.

Despite the age difference — Max was forty-six and Leonora twenty — and Max’s existing marriage to a woman called Marie-Berthe, they “became lovers almost instantly.” Max also gave her a new nickname, one more in keeping with her wild spirit and love of animals: Bride of the Wind. He was Loplop, the bird that was his Surrealist alter-ego. The horse and the bird would appear time and time again in their later paintings, and also in Leonora’s fiction.

When word of their relationship reached Lancashire, it so angered Leonora’s father that he attempted to have Max arrested for exhibiting pornographic material. Harold was a traditionalist, perplexed by his daughter’s rebelliousness and unwilling to countenance any compromise to his authority.

Leonora’s feelings towards her father and his stance are most clearly expressed in her short story “The Oval Lady,” written later in 1939, in which the main character Lucretia has a difficult relationship with her father. “I don’t drink, I don’t eat,” she says in response to the offer of a cup of tea. “It’s a protest against my father, the bastard.”

Later in the story, Lucretia’s father burns her most treasured possession, a rocking horse called Tartar, and Lucretia has to cover her ears to drown out the “most frightful neighing [that] sounded from above, as if an animal were suffering extreme torture.” Harold never burned Leonora’s rocking horse, but clearly, he was capable of inflicting extreme emotional pain on his only daughter, whether intentionally or not, and the arrest warrant for Max was the last straw.

Leonora and Max fled London for Cornwall, where they had been invited by Roland Penrose to stay at Lambe Creek House, deep in the countryside beyond Truro. Many other artists were also there that summer, in a hedonistic house party that has since been described as the biggest gathering of Surrealists in Britain.

Guests included Paul Éluard, Man Ray, Eileen Agar, and Henry Moore, and the heady weeks were immortalized in photographs by Lee Miller (Miller was to take the most iconic photos of Leonora). From there the couple went directly to France, and Leonora never saw her father again.

. . . . . . . . . .

Portrait of Max Ernst, 1939

. . . . . . . . . .

The French years

1938 saw Max and Leonora first in Paris (where Leonora met and got on well with Max’s son, Jimmy) and then to a cottage in Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche in the Rhône Valley. Between them, they covered the interior with murals of fish and lizards, women, horses, and a vibrant red unicorn.

Sculptures were designed for the terrace and peacocks were bought to roam the yard. At first, they took pains to keep their whereabouts a secret, but in time there were visitors, including Leonor Fini and Man Ray.

In the spring of that year, Leonora also published her first short story in pamphlet form, called “The House of Fear.” It was a small print run of 120 copies and something of a public declaration of her relationship with Max, who provided both illustrations and an introduction.

However, there were complications. Their idyll was rapidly being overshadowed by the tide of Fascism sweeping across Europe. It also turned out that moving from Paris was not enough to keep Max’s wife Marie-Berthe away: she followed them south, and Max had to take her back to Paris.

For a time Leonora was left hanging in the balance, unsure of whether Max would return to her and keenly aware of how precarious her situation was. He did return, in the new year of 1939, and never saw his wife again, but Leonora never forgot how she had had to fight, as she saw it, for him.

Later, she fictionalized the acrimonious triangle in her novella Little Francis, in which Uncle Ubriaco (Max) is a kindly man whose fourteen-year-old daughter, Amelia (Marie-Berthe) is wildly jealous about his relationship with a young nephew, Francis (Leonora).

Leonora’s relationship with, and place within, the Surrealist group was also difficult. Max was one of the most prominent members and certainly one of the most famous, and Leonora’s name was now connected with his. However, the Surrealists generally were not progressive in their views towards women, seeing them as bodies to be manipulated both in art and in life: they were artificial beings with no desires or will of their own.

Other women were challenging this notion, including Lee Miller and Eileen Agar. Leonora was determined that she would never be simply Max’s muse. She was an artist and author in her own right and never content to play the role set out for her.>

Many of her short stories, in particular, are more or less explicit retorts to the Surrealist view of women, and she told Joanna Moorhead that every piece of writing she had ever done was more or less autobiographical. She did, however, also recognize the enormous influence Max had on her and her work: “He educated me a lot. Really educated me — a proper education, not a convent education.”

. . . . . . . . . .

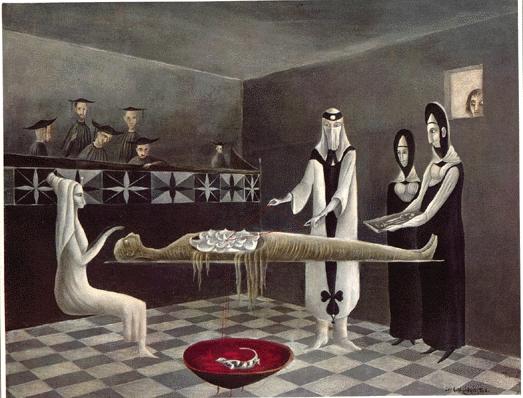

Amor Che Move il Sole et l’Altre Stelle (1946)

. . . . . . . . . .

The difficulties of war

Just after the outbreak of war in September 1939 Max, as a German citizen, was interned at the prison in Largentière as an undesirable foreigner, before being moved to an internment camp near Aix-en-Provence. Leonora did everything she could think of to get him released, writing to several friends who had connections.

Many could or would not help, but finally in December, thanks to the intervention of Paul Éluard, Max returned to Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche. Their life resumed with an intense quietness and domesticity, perhaps brought about by the realization of what they had so nearly lost.

Leonora’s letters from this period emphasized daily life, and in particular on food — an indication of her love of cooking and inventing new dishes, but also a response to the scarcity that was beginning to bite. To Leonor Fini, in January 1940, she wrote that she made a “good dish” from chopped onion, rice, canned tuna, beaten eggs, and black olives, all topped with a sauce made from tomatoes, more onions, olives, and cream.

At the same time, she was beginning to have doubts about the relationship. She was under no illusions that Max, being so much older, was also something of a father figure, and she was beginning to wonder whether she needed or wanted one.

In May 1940 Max was arrested again, this time for producing what the Germans deemed to be “degenerate” art. He returned to the prison at Aix-en-Provence, and this started a spiral of depression and severe anxiety for Leonora: left behind alone in their cottage, she spent the first day of his absence drinking orange blossom water to induce vomiting.

Later, she wondered if this was not “an unconscious desire to get rid for the second time of my father: Max, whom I had to eliminate if I wanted to live.” Convinced by friends to sell the cottage and flee to Spain, she was ridden with guilt and grief over leaving him, but at the same time increasingly determined to save herself.

Flight to Spain and journey to madness

Later, Leonora would describe how this conflict of emotions left her feeling “jammed.” In the flight from France to Spain — a flight that also became one of sanity to madness as her fragile mental health deteriorated into a psychotic break.

Max was quickly forgotten in her quest to find a way beyond the body that she increasingly felt was caging her spirit and preventing her from realizing her full potential as multiple beings: “an androgyne, the Moon, the Holy Ghost, a gypsy, an acrobat, Leonora Carrington, and a woman.”

She became convinced that she had been chosen to play a pivotal role in Europe at this time of trouble and that Madrid was the place where she would realize this destiny. Madrid, she wrote, “was the world’s stomach and I had been chosen for the task of restoring this digestive organ to health.”

In August 1940 she was institutionalized on the orders of her father back in Lancashire and taken to a clinic in Santander for psychiatric patients called Covadonga.

The head clinician, Dr. Morales, was a proponent of an experimental treatment that involved injecting the patient with Cardiazol, a drug that induced epileptic fits. Leonora, who later always referred to the clinic as “the madhouse” or ‘the asylum’, was subjected to three of these treatments, and in between was stripped naked and strapped to a bed.

Her visions during this time led her to a place which she called ‘Down Below’, in which she believed she was the third person of The Trinity, and where her reason for being was to “stop the war and liberate the world.”

In her memoir Down Below, written in 1944, she recalls this time and summons the reader:

“I must live through that experience all over again, because, by doing so, I believe that I may be of use to you, just as I believe you will be of help in my journey beyond that frontier by keeping me lucid and by enabling me to put on and to take off at will the mask which will be my shield against the hostility of Conformism.”

She was eventually released in December 1940 after the intervention of a distant cousin, Guillermo Gil, who was a doctor at the general hospital in Santander. Her family had decided that she would travel to Lisbon, and from there by ship to South Africa where she would be admitted to another sanatorium. The journey would be undertaken in the care of her nurse from Covadonga, Frau Asegurado.

Escape in Lisbon

When they stopped off in Madrid en route to Lisbon, Leonora by chance met a friend from her Paris days, Renato Leduc. He was a handsome man, a Mexican revolutionary who had turned to poetry and was now traveling around Europe, sponsored by the Mexican government and working for the Mexican embassy in Paris.

Like Ernst, Leduc was older than Leonora, age forty-two to her twenty-three. He, too, was on his way to Lisbon, intending to leave Europe for the war and sail back to New York. Realizing Leonora’s predicament, he suggested that she travel to Lisbon with the nurse as arranged, but once there, find some means of escape and make her way to the Mexican embassy.

Leduc would meet her there, and help her get a visa for the U.S. In a story that seems like something out of a thriller novel, it worked: in Lisbon, Leonora, having made the excuse that she needed to shop for new gloves, escaped from her nurse through the back door of a café and met Renato at the Embassy.

There they made plans for a marriage of convenience, one which also held a spark of attraction for both of them, and which ensured Leonora was safe.

Lisbon at the time was a hub on the edge of Europe: a place seething with refugees and spies, the only port that offered passage to the United States and freedom. While Leonora and Renato waited — for papers, for places on a ship, for a date they could be married at the British Embassy. Leonora wandered the city, often meeting people she knew from France who were also fleeing the Germans.

It was perhaps inevitable that, one day she bumped into Max. He had recently been released and had made his way to Lisbon via Marseilles with the help of Peggy Guggenheim, his patron and a committed supporter of the arts. Peggy and Max had begun an affair, and the situation became awkward and uncomfortable as it became clear that Max was still very much in love with Leonora, while Peggy had fallen in love with him.

The group that formed in Lisbon was, Leonora admitted later, “very strange indeed,” consisting as it did of Leonora, Renato, Max, Peggy, Peggy’s ex-husband Laurence Vail and his new wife Kay Boyle, Peggy and Laurence’s two children Sindbad and Pegeen, and the four daughters of Laurence and Kay.

On July 11, 1941, having married at the British Consulate-General on May 26, Leonora and Renato left Lisbon on board the SS Exeter. Peggy and her extended entourage followed two days later on a Pan-Am Clipper, a luxury aircraft with a bar and dining room onboard, and which took just twenty-four hours to reach New York via the Azores.

. . . . . . . . . .

Adieu Ammenotep 1960 by Leonora Carrington

. . . . . . . . . .

A new life in New York

Once in New York, Renato was keen to resume something of his old life and spent a lot of time working and socializing until the early hours of the morning. Leonora filled the gap he left by spending time with Max, but despite his continuing eagerness to return to their previous relationship, she didn’t reciprocate his feelings.

She was beginning to see clearly what Peggy later wrote so succinctly in her memoirs: that Max was like a demanding small child, who “always wanted to be the center of attention” and who “always tried to bring all conversations around to himself …”

Leonora had no desire to be absorbed into his life and his art, nor to play the shadow to someone whose fame had reached the shores of American before he had.

Caught between his commitment to Peggy and his feelings for Leonora, Max decided to marry Peggy; when Renato decided to leave New York for his native Mexico at the end of 1942, Leonora went with him.

She never saw Max again. Her final farewell to him came in the form of a short story, “The Bird Superior,” in which she brought together their Surrealist alter egos, the bird and the horse, one last time.

Another new life in Mexico

In Mexico City, Leonora found a ready-made community of artists and writers, many of them also communists and socialists in exile from fascist Europe and the US. While she was never close to the Mexican artists (Frida Kahlo apparently called Leonora and her circle “those European bitches”), she gathered around herself a kind of Surrealist family that would be her anchor for the next several decades.

Her marriage to Renato gradually foundered, but their final divorce in 1943 was not acrimonious: the marriage had been more than one of convenience, but there was not enough between them for it to work long-term.

Instead, she formed deep friendships, in particular with the French poet Benjamin Péret and his Spanish lover, the painter Remedios Varo, and with the Hungarian photographer Kati Horna and her sculptor husband José.

She also began a new relationship, with another Hungarian photographer named Emerico Weisz Schwartz, known to all as Chiki, and the two married in 1946 when Leonora discovered she was pregnant. Her first son Gabriel was born on 14 July, followed just 16 months later by Pablo.

Her relations with her English family, however, were tenuous. Her mother visited Mexico City for the birth of Pablo in 1947, but the relationship was later damaged beyond repair after Harold died in 1950. Leonora made the long trip back to England in 1952, but the visit ended disastrously as her brothers effectively cut her out of her inheritance. After she returned to Mexico, she never saw any of them again.

Remedios Varo and The Hearing Trumpet

Within this group, her most important friendship was with Remedios Varo. The two women considered themselves to be sisters and kindred spirits: the poet Octavio Paz called them Dos Transuentes, the two passers-by, “two bewitched witches” who shared the same passion for Surrealism and for creating work outside of boundaries and constraints.

They saw each other almost every day until Remedios died in 1963. When Leonora wrote her novel The Hearing Trumpet in the 1950s, she based the character of Carmella Valasquez on Remedios.

The Hearing Trumpet, recently reissued after its original publication in 1977, is Leonora’s best-known written work. It epitomized and expanded on what art academic Gloria Orenstein called Leonora’s “modern women’s codex” for a “joined-up world…a new formulation of both reality and identity, of space, time, self, and cosmic history.”

The story centers around Marian Leatherby, a 92-year-old British woman living in a Spanish-speaking country, who is placed into a care home by her son and his wife. She overhears their plans for her after a friend, Carmella, gifts her a hearing trumpet: listening through walls and floors, she realizes that her son has misgivings, but her daughter-in-law views her as expendable, a nuisance to be thrown away and forgotten about.

Notable for its complex portrayal of being a later-life woman, The Hearing Trumpet is also intensely surreal and mystical, and uncompromising in the way it reveals society’s views of older people: Marian’s grandson, for example, sees his grandmother as a “drooling sack of decomposing flesh.”

The old people’s home is a monstrosity, home to The Well of Light Brotherhood, a place that provides nothing in the way of care for its residents and exists only to line the pockets of its owner, and in which the narrative shifts through time and space. The Hearing Trumpet is considered a masterpiece of Surrealism, and many of its themes are still relevant today.

. . . . . . . . . .

Leonora in her studio, 1956. Photo by Norah Horan

. . . . . . . . . .

Art and creativity

Another important figure in Leonora’s new Mexican life was Edward James, a British art collector who championed her work and became her patron. It was he who described her studio in the small family apartment as “small in the extreme … ill-furnished and not very well lighted…the disorder was apocalyptic: the appurtenances of the poorest.”

James had always, he said, noticed that there was an “inverse ratio” between the luxuriousness of a studio and the true worth of the artist’s art, and as soon as he saw Leonora’s his hopes “began to swell.” His patronage was vital at a time when her work was becoming better known, and often acted as liaison when she was unable to attend her own shows due to her parenting responsibilities.

During this period, Leonora also experimented with traditional craftsmanship, such as embroidery, appliqué, and woodwork. Far more than in Europe, Mexico allowed her to explore a woman-centered version of Surrealism; she delved into the tarot, Mayan and astrological imagery, Kabbalah, and Buddhism.

She made dolls for her children and cooked for everyone — outrageous, surreal meals that were a continuation of her French experiments,where everyone would gather around the table speaking a mixture of English, Spanish, and French. These meals, according to Joanna Moorhead, were an excuse to “celebrate the ridiculousness of rules, and to break them.”

At one meal, they served pearl tapioca colored with squid ink, claiming it was a rare and expensive caviar; at another, the food was said to induce dreams of being the King of England. Cooking and painting were closely intertwined for Leonora:

“The real work is done when you are alone in your studio. First it becomes a sense of something and then it becomes something that you can see and then it becomes something that you can do. It’s like cooking, but cooking isn’t that easy either.”

“Exile” in the U.S.

After twenty years Leonora’s life was once again disrupted. In 1968, with the upcoming Olympic games in Mexico City, student demonstrations and strikes against poverty and the conditions of the working class reached a crescendo, and hundreds were killed when government forces opened fire on a peaceful protest.

Although she generally kept out of politics, Leonora was inspired to attend some anti-government meetings. Her name was subsequently placed on a watchlist and, aware that she was likely to be arrested, she fled — without Chiki — to New York.

She remained in the U.S. for the next twenty-five years, always living alone in rented accommodations and often in poverty.Chiki sent her what money he could from Mexico, and she continued to paint and to write, but she never settled. She always felt, she said, at home in Mexico, although “as one does in a familiar swimming pool that has sharks in it,” and she finally returned for good in 1983.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Last years in Mexico

Leonora felt the onset of old age keenly but, with characteristic stubbornness, was determined not to let it stop her, and she was generally in good health. Her last years were still full of art and creativity but marked by the dwindling of her group of contemporaries. José Horna had died the same year as Remedios, in 1963. His wife Kati died in 2000, and Chiki in 2007 at the age of ninety-six.

The only surviving member of the international Surrealist circle was Dorothea Tanning, who Leonora had never met. More and more, her life revolved around her two sons, who now also had families of their own; Gabriel in Mexico City and Pablo in the US. Leonora was still active, visiting Gabriel for lunch and talking regularly to Pablo on the phone, until May 2011, when she contracted pneumonia.

To those who knew her it seemed inconceivable that she would succumb, that she would not make the one-hundredth birthday milestone that she had been so determined to reach, but she died in a hospital at the age of ninety-four.

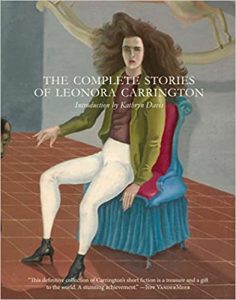

Since her death, her artwork continues to be popular, often selling for millions of dollars, and is included in exhibitions worldwide almost every year. Her writing, too, has undergone a resurgence, with the reissuing of The Hearing Trumpet and various volumes of her Surrealist short stories.

On what would have been her ninety-eighth birthday, in 2015, she was given an ultimate honor of the digital age, a Google Doodle based on her painting How Doth the Little Crocodile.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

More about Leonora Carrington

Books by Leonora Carrington

- La Maison de la Peur (1938; illustrations by Max Ernst)

- Down Below (1944; reprinted 1983, 2017)

- Une chemise de nuit de flanelle (1951)

- The Oval Lady: Surreal Storie (1975)

- The Hearing Trumpet (1976, 2021)

- The Stone Door (1977)

- The Seventh Horse and Other Tales (1988)

- The House of Fear (1988)

- The Milk of Dreams (1917)

- The Debutante and Other Stories (2017)

- The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington (2017)

- Down Below (2017)

- The Skeleton’s Holiday (2018)

Art

- Leonora Carrington Artworks

- Leonora Carrington at the Museum of Modern Art, NY

- Leonora Carrington Brought a Wild, Feminist Intensity to Surrealist Painting

Biography and art criticism

- Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy, and Art by Susan Albreth (2010)

- Surreal Friends: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna by Stefan Van Raay et al. (2010)

- The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington by Joanna Moorhead (2017)

- Out of This World: The Surreal Art of Leonora Carrington (children’s book; 2019)

- The Invisible Painting: My Memoir of Leonora Carrington by Gabriel Weisz Carrington (2021)

More information

- Leonora Carrington: The Lost Surrealist (documentary)

- NY Times Obituary

- Wikipedia

- Leonora Carrington and the Theatre (panel discussion)

- Writing and Painting with Both Hands

Leave a Reply