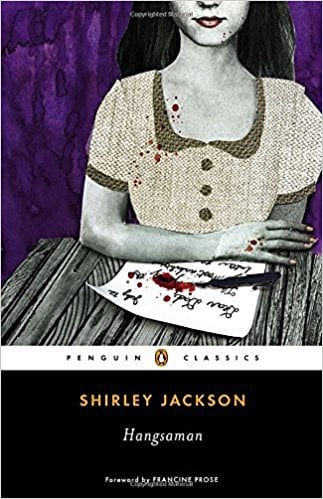

Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson, 1951 — an Analysis

By Francis Booth | On March 31, 2021 | Updated April 23, 2023 | Comments (3)

This analysis of Hangsaman, Shirley Jackson’s chilling and thought-provoking 1951 novel, is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

In a 1956 book called Sex Variant Women in Literature, the academic critic, Jeanette H. Foster referred to Hangsaman as “an eerie novel about lesbians.’ This is a bizarre reading of the novel and Shirley Jackson was incensed. Her biographer, Judy Oppenheimer, quoted her as saying:

“I happen to know what Hangsaman is about. I wrote it. And dammit it is about what I say it is about and not some dirty old lady at Oxford. Because (let me whisper) I don’t really know anything about stuff like that. And I don’t want to know… I am writing about ambivalence but it is an ambivalence of the spirit or the mind, not the sex. My poor devils have enough to contend with without being sex deviates along with being moral and romantic deviates.”

Because she had children of her own, and wrote innocuous books and magazine pieces about her charming but chaotic family life, Shirley Jackson presumably found it quite difficult to write about sex. So she didn’t. Does Natalie Waite in Hangsaman go the whole hog? If so, with whom: is it with an older man, one of her father’s friends, or even perhaps her father himself? We don’t know.

As in Heinrich von Kleist’s The Marquise of O there is a lacuna around Natalie’s first – possible – experience of sex; perhaps the experience was so awful that she has erased from her mind and Jackson has erased it from the novel.

It feels almost as if some clumsy censor has excised a whole section that would have described her experience. But neither at the time it happens nor later in the novel are we given any idea of what actually happened; we know Natalie has been irrevocably changed but not by what exactly.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Shirley Jackson

. . . . . . . . . .

Not initially a critical success

The critics at the time were not always kind to Hangsaman: The Saturday Review, May 5, 1951, compared Hangsaman to Jackson’s notorious short story The Lottery, where villagers choose one person a year to be stoned to death, which had been published not long before and caused an enormous – almost entirely negative – response.

“Now in the novel Hangsaman and on its much larger scale Miss Jackson again proceeds from realism to symbolic drama. Here the method fails. The tones do not flow into one another … Like many another story, this one is about the maturing of an adolescent. Natalie Waite, though, is a very special seventeen; not so much in her un-adult trick of occasionally blurting out exactly what she is thinking as in the quality of her thinking and in her literary background.

Natalie is an exceptionally talented, intellectual child, already supervised by her father, who is apparently a sort of critic and certainly an egotistical fool … Natalie was raped or seduced offstage at her father’s cocktail party.

Presumably the emotional effects were profound, but we don’t know any more about them than we know, for instance, about the effects of a flock of martinis Natalie absorbed one afternoon and for the first time. Miss Jackson’s method of not-quite-telling begins to show its disadvantages.”

Another review of the time, in The Age, from Melbourne Australia, February 1952, was titled “A Novel of Emotional Bewilderment”:

“Shirley Jackson, with the acuteness of a surgeon, lays bare the tissue and nerves of adolescent emotions in her novel, Hangsaman. She portrays the period between childhood and maturity in the life of an American girl when self assumes immense proportions and demands constant dramatization, gaining importance and size in these imaginary flights …

This story is one to bring terror to the heart of a parent sending an unadaptable child out among her fellows. One would think that it must surely be autobiographical, so deeply has the author plunged in her description of the cruelty girls can deal one to another and of the brutality with which the can win a place in the mob.

It is a harrowing and particularly vicious picture and not an easily assimilated one. Incidents are part of the general emotional bewilderment of scenes that build to a climax, leaving the reader to wonder to the last moment whether Natalie will escape.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom is available on Amazon US and Amazon UK

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

A contemporary re-evaluation of a fine coming of age novel

Despite the critics, the writing in Hangsaman is controlled and masterly; it is one of the finest of all coming of age novels. There is a wonderful passage where Jackson describes the crucial moment of adolescence where the girl becomes the woman, with her own will and a personality separate from that of her parents and family.

For Jackson, naturally, this transition is effected by creativity, in this case, as in Jackson’s, the creativity of writing.

There was a point in Natalie, only dimly realized by herself, and probably entirely a function of her age, where obedience ended and control began; after this point was reached and passed, Natalie became a solitary functioning individual, capable of ascertaining her own believable possibilities.

Sometimes, with a vast aching heartbreak, the great, badly contained intentions of creation, the poignant searching longings of adolescence overwhelmed her, and shocked by her own capacity for creation, she held herself tight and unyielding, crying out silently something that might only be phrased as, “Let me take, let me create.”

If such a feeling had any meaning to her, it was as the poetic impulse which led her into such embarrassing compositions as were hidden in her desk; the gap between the poetry she wrote and the poetry she contained was, for Natalie, something unsolvable.

Along the same lines, one of Natalie’s father’s friends says to her: “Little Natalie, never rest until you have uncovered your essential self. Remember that. Somewhere, deep inside you, hidden by all sorts of fears and worries and petty little thoughts, is a clean pure being made of radiant colors.”

This is “so much like the things that Natalie sometimes suspected about herself,” that she asks, “how do you ever know?”

. . . . . . . . . .

Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson: A Review

. . . . . . . . . .

A heroine who lives in her head

Like a true creative spirit, Natalie lives mainly in her head, in a fantasy world which includes, as the novel opens, a kind of noir detective story where she is a suspect. Whatever she is doing, the story keeps playing out in her mind and in the narrative, a story where she is the central figure, the protagonist, the heroine.

This is a very common adolescent fantasy and Natalie’s character in her own story is rather like the many girl detective stories of the time, though at seventeen she is rather too old for this kind of fiction, at which her writer father would no doubt sneer.

“Natalie, fascinated, was listening to the secret voice which followed her. It was the police detective and he spoke sharply, incisively, through the gentle movement of her mother’s voice. ‘How,’ he asked pointedly, ‘Miss Waite, how do you account for the gap in time between your visit to the rose garden and your discovery of the body?’”

This particular fantasy stops when she goes to college, to be replaced by another, her imaginary friend Tony (female, despite her name); more of her shortly. Natalie is about to leave for college as the novel opens; she is “desperately afraid,” even though the college is only thirty miles away and is the one that her father has chosen for her. Here Jackson describes the unbridgeable gulf between a teenager and her parents:

“Natalie Waite, who was seventeen years old but who felt that she had been truly conscious only since she was about fifteen, lived in an odd corner of a world of sound and sight past the daily voices of her father and mother and their incomprehensible actions.

For the past two years – since, in fact, she had turned around suddenly one bright morning and seen from the corner of her eye a person called Natalie, existing, charted, inescapably located on a spot of ground, favored with sense and feet and a bright-red sweater, and most obscurely alive – she had lived completely by herself, allowing not even her father access to the farther places of her mind.”

The father-daughter dynamic

Nevertheless, like other teenage girls in Girls in Bloom, she is close to her father, a writer, who critiques her writing as if he were her mentor rather than her father.

In this she is very close to Cassandra Mortmain in I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, a novel which also prefigures Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Her father is kindly but patronizing towards Natalie, who he says is ‘too untaught for literature and too young for drink.”

Natalie’s father is also no doubt to some extent a portrait of Jackson’s husband, Edgar Hyman, a critic and book reviewer whose relationship with Jackson is presumably in some ways portrayed in Natalie’s relationship with her father.

“Do you realize I’m two weeks behind in my work?’ he asks his wife. ‘I’ve got to review four books by Monday; four books no one in this house has read but myself… Not to mention the book.”

At the mention of his book, “his family glanced at him briefly, in chorus, and then away;” no doubt Hyman and Jackson’s family reacted similarly.

Hyman’s heavyweight The Armed Vision: A Study in the Methods of Modern Literary Criticism was published in 1947, his next book, The Critical Performance: An Anthology of American and British Literary Criticism in Our Century was published in 1956, nine years later and his third, Poetry and Criticism: Five Revolutions in Literary Taste in 1961.

Shirley Jackson’s life in the period of this novel

In this period, Jackson published five novels (with another in 1962), two collections of her lightweight – as both she and Hyman saw them – magazine pieces, a collection of short stories and numerous individual stories in magazines.

But this was at a time when a woman’s place was in the kitchen and her role was, as Virginia Woolf said, to magnify her man’s reflection in the mirror of her self; no doubt both Hyman and their friends saw his work as the most important thing, as do Natalie’s family.

Unlike Woolf, Jackson did not have a room of her own and had to be Woolf’s ‘angel in the house,’ though she was hardly the soft, gentle, beautiful, radiant type of angel. In the introduction to Just an Ordinary Day, a posthumous collection of Jackson’s stories, two of her children wrote about how she balanced domesticity and creativity.

“Our mother tried to write every day, and treated writing in every way as her professional livelihood. She would typically work all morning, after all the children went off to school, and usually again well into the evening and night. There was always the sound of typing.

And our house was more often than not filled with luminaries in literature and the arts. There were legendary parties and poker games with visiting painters, sculptors, musicians, composers, poets, teachers, and writers of every leaning. But always there was the sound of her typewriter, pounding away into the night.”

This is very much a description of the literary garden parties that Natalie’s father hosts on Sundays, which are rather reminiscent of the Ramsay’s dinner party in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, whose modernist pretensions Jackson nicely deflates.

It is after one of these parties that Natalie – probably – has her first sexual experience; it is foreshadowed when her father says to her: “Daughter mine … has anyone yet corrupted you?”

Someone is about to:

“… She was almost sure of this, the preliminary faint stirrings of something about to happen. The idea once born, she knew it was true; something incredible was going to happen, now, right now, this afternoon, today; this was going to be a day she would remember and look back upon, thinking, That wonderful day … the day when that happened.”

An older man, who is not named and whom she does not seem to know, asks her to sit down: “He was old, she could see now, much older than she had thought before. There were fine disagreeable little lines around his eyes and mouth, and his hands were thin and bony, and even shook a little.”

He tells Natalie that her father has described her as “quite the little writer … Obviously meaning to make her sound less like her mother and more like a frightened girl not yet in college.”

Natalie is hurt by this and responds, “I suppose you probably want to write too?” Natalie tries to get up to leave but he holds onto her. “A little chill went down Natalie’s back at his holding her arm, at the strange unfamiliar touch of someone else.” In Natalie’s head the detective says to her: “This you will not escape.” The “strange man” leads Natalie away. She has been telling him about “how wonderful I am.”

They end up in the woods where Natalie used to play when she was a child: “The trees were really dark and silent, and Natalie thought quickly. The danger is in here, in here, just as they stepped inside and were lost in the darkness.”

They sit down the grass. Oh my dear God sweet Christ, Natalie thought, so sickened she nearly said it aloud, is he going to touch me? If he does, Jackson does not tell us.

The next paragraph has Natalie waking up the next morning, “to bright sun and clear air,” before burying her head in the pillow and saying:

“‘No, please no’.

‘I will not think about it, it doesn’t matter,’ she told herself, and her mind repeated idiotically, It doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter, until, desperately, she said aloud, ‘I don’t remember, nothing happened, nothing that I remember happened.’

Slowly she knew she was sick; her head ached, she was dizzy, she loathed her hands as they came toward her face to cover her eyes. ‘Nothing happened,’ she chanted, ‘nothing happened, nothing happened, nothing happened, nothing happened.’

… Someday, she thought, it will be gone. Someday I will be sixty years old, sixty-seven, eighty, and, remembering, will perhaps recall that something of this sort happened once (where? when? who?) and will perhaps smile nostalgically thinking, What a sad silly girl I was, to be sure.’”

Before whatever happened, happened, the detective in Natalie’s head had said to her: ‘No one can live through such things and not remember them,’ but Natalie is determined not to remember and Jackson is determined not to tell us.

She does tell us that “the most horrible moment of that morning or any morning in her life, was when she first looked at herself in the mirror, at her bruised face and her pitiful, erring body,” but none of her family notice anything wrong with her face and perhaps the bruising is entirely internal.

Later, at college, she writes in her private journal, where she splits off a separate personality and talks to herself in the third person:

“Perhaps, you thought, Natalie is frightened and perhaps she even thinks sometimes about a certain long ago bad thing that she promised me never to think about again. Well, that’s why I am writing this now. I could tell, my darling, that you are worried about me. I could feel you being apprehensive, and I knew what you were thinking about was you and me.

And I even knew that you thought I was worried about that terrible thing, but of course – I promise you this, I really do – I don’t think about it at all, ever, because both of us know that it never happened, did it? And it was some horrible dream that caught up with us both. We don’t have to worry about things like that, you remember we decided we didn’t have to worry.”

She does leave for college, where, unlike her mother and her author, Natalie has a room of her own, “the only room she had ever known where she would be, privately, working out her own salvation.” The college is described as being very much like the liberal, girls-only Bennington College in Vermont where Jackson’s husband Edgar Hyman taught.

There Natalie meets a professor, Arthur Langdon, who seems to be another portrait of Hyman (even their names are concordant). Langdon has a wife who, like Natalie’s mother but completely unlike Jackson herself is entirely subsumed under her husband’s ego and has, as Hyman undoubtedly did, a circle of young, devoted female admirers.

Langdon soon steps into the role that had been filled by Natalie’s father, and gives Jackson another chance to muse on the absurdity of being a writer.

“‘I find your criticisms very helpful,’ Natalie said demurely. ‘My father discusses my work with me very much as you do.’ She thought of her father with sudden sadness; he was so far away and so much without her, and here she was speaking to a stranger.

‘Do you plan to be a writer?’

A what? Natalie thought; a writer, a plumber, a doctor, a merchant, a chief; the best-laid plans of; a writer the way I might plan to be a corpse? ‘A writer?’ she repeated, as though she had never heard the word before.”

Natalie make some friends at the college and fits in well enough, though she is never part of any crowd, too bookish and self-sufficient for the rest of the girls. One friend says that the other girls accuse her of sitting in her room all day and never going out; “They say you’re crazy. You sit in your room all day and all night and never go out and they say you’re crazy… you’re spooky.”

Natalie’s answer to this comes in her own private journal, which Jackson allows us limited access to:

“Dearest dearest darling most important dearest darling Natalie – this is me talking, your own priceless own Natalie, and I just wanted to tell you one single small thing: you are the best and they will know it someday, and someday no one will ever dare laugh again when you are near, and no one will dare even speak to you without bowing first. And they will be afraid of you. And all you have to do is wait, my darling, wait and it will come, I promise you.”

Later it seems that Natalie has split herself into two in a different way: by inventing a female friend named Tony. It’s not entirely clear at first that Tony is imaginary but after much romantic talk – not romantic in the lesbian sense, despite what Jackson’s Oxford critic said – about traveling the world together they end up alone in a dark wood, where Tony disappears.

This time, nothing bad happens to Natalie in the woods and a friendly couple in a car pick her up and take her back to town, drop her off at the bridge where she appears for a moment to contemplate suicide.

But then, one with herself again, she heads back to the college; she has come of age. “As she had never been before, she was now alone, and grown-up, and powerful, and not at all afraid.”

More about Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- You Might Never Find Your Way Back: Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman

- Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman — what does it mean?

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture.

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

Tony is NOT imaginary. Multiple people see her. After Tony sits with Natalie on the Langdon’s porch and Natalie goes inside, Elizabeth Langdon comments that she saw her on the porch with someone. The one-armed man definitely sees Tony. She butters his rolls for him and then says something vaguely insulting to him. He asks Natalie what’s wrong with her friend. Tony being unkind to a disabled person was the first sign that she might not be a good person. The bus driver also sees Tony. Her father’s warning about her enemies coming from the same place her friends came from rang true here.

Alex, there are various readings of whether Tony is real or a figment of Natalie’s imagination. Most, I would say, conclude that Tony is imaginary. Here’s one, and there are many others: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/books/what-to-read/madness-gaslighting-abuse-dark-story-behind-shirley-jacksons/ — still, Jackson, with her great skill, leaves this matter just ambiguous enough to spur this kind of debate.

Natalie is an unreliable narrator. I got that Tony was imaginary, possibly a delusion/halucination from the very beginning.