Her First Time: Seduction and Loss of Innocence in 1920s Women’s Novels

By Francis Booth | On December 13, 2021 | Updated November 18, 2024 | Comments (0)

How was seduction, loss of virginity, unplanned pregnancy, unbidden passion, and occasional betrayal portrayed in English and American novels of nearly one hundred years ago? This sampling of stories of seduction and loss of innocence in 1920s women’s novels — by women authors — is fascinating and illuminating.

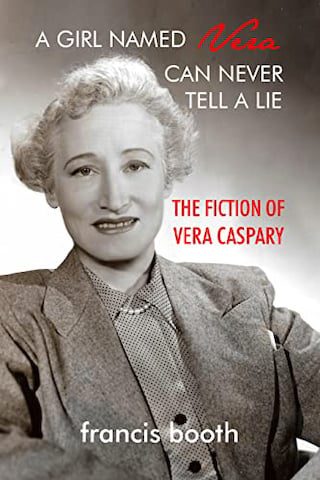

Here we’ll explore works by Vera Caspary, Viña Delmar, Ellen Glasgow, Edna Ferber, E. Arnot Robinson, and Rosamond Lehmann. Excerpted from A Girl Named Vera can Never Tell a Lie: The Novels of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth. Reprinted with permission.

. . . . . . . . .

Music in the Street by Vera Caspary (1929)

In Vera Caspary’s Music in the Street (1929) Mae Thorpe moves away from her small-town family into a working girls’ home in Chicago, where at first, she is one of the unpopular girls with no boyfriend who stays home on a Saturday night. Then Mae finds a man, though he is by no means the kind of boy the popular girls would envy: Olyn is an artist, an intellectual, shy, socially awkward, and worst of all, poor and living at the YMCA.

“While Olyn was regarded suspiciously by the more hilarious because he neither smoked nor drank, he was accepted as Mae’s boyfriend. The girls teased her about him, made fun of his large collars and long neck, mocked his slow, serious manner of speaking, but they expected Mae to marry him.”

Still, despite Olyn taking her to the Art Institute of Chicago and other places her housemates would sneer at, when the phone rings at Rolfe House and her name is called, Mae feels as though she has finally made it.

“Mae stepped forward with an air of importance. She was being called by her boyfriend and she had a large audience.” And when they go out together, Mae feels she has become part of the life of the city at last. Read more about Music in the Street.

. . . . . . . . .

Bad Girl by Viña Delmar (1928)

It’s interesting to compare the description of Mae’s first time with an equivalent passage in a more deliberately sensational novel from the year before that has several parallels to Music in the Street: Viña Delmar’s Bad Girl (1928).

Dot is also a working girl like Mae, but unlike Mae she still lives with her father and overprotective brother; he is so overprotective that it is the fear of going home late that makes her stay the night with boyfriend Eddie.

At first, like Mae, Dot goes as far as passionate kissing, but no further. “Dot felt his hand on her knee. It was indecent. She could not discourage it without shaking off his kiss, and the kiss was very sweet.” But Eddie doesn’t want to stop. And Dot is not sure if she wants him to. Here is Delmar’s description of Dot’s becoming the “bad girl” she has always been warned about.

“You see, I ain’t used to stopping. You get what I mean?”

“Yes, I get it.”

“Well, it looks like a kiss or so is all you want out of this thing. You’re not upset if we stop after hot loving.”

“Is that so?” Asked Dot, unexpectedly.

“Are you? Do you feel that there should be more?”

He sat up suddenly on the edge of the bed and looked down at her with hope and incredulity mixed in his expression. She said nothing. She was thinking of what it would be like to be a bad girl. People would know about it perhaps. Eddie might tell. Then she’d have to go away to a place where nobody knew her.

“Dot, answer me.”

She said what was on her mind. “I’d be a bad girl.”

“No, you wouldn’t. Bad girl is something different. You’d never let anybody else touch you, would you?”

“I don’t know,” she said after a minute’s hesitancy. “I never thought I would let you go the whole way with me.”

It took time for the full meaning of her words to penetrate. When it did he looked at her face and found that her eyes had been waiting to meet his. “Do you mean that you’re going to let me?”

“I guess so, Eddie.” Pause. “Yes, I’m going to let you.”

“Now?”

“If you want to.”

“If I want to? Gee, Kid, you say crazy things.”

In Music in the Street, Boyd had tried the same argument with Mae – if you only go with one man, you’re not a bad girl. “What would you think of me if I slept with any man that asked me?”

And Boyd had had a very similar response to Eddie’s. “I’d think you were a tart. But I’m not any man, am I? All these weeks, Mae, I’ve been trying to show you that I wasn’t just trying to make you. I didn’t think there were girls like you anymore. I thought the species was extinct. All the girls I know are broadminded.”

. . . . . . . . .

So Big by Edna Ferber (1924)

In Edna Ferber’s So Big, the bestselling (and subsequently Pulitzer Prize-winning) novel of 1924, there is a different kind of seduction scene from the two we have just seen: this time the man isn’t a cynical chancer from the big city constantly badgering the girl to go further.

After her itinerant gambler father dies, Selina has moved ten miles outside Chicago to teach in a rural Dutch settlement. She is giving private lessons to the simple, “gentle giant” Pervus de Jong, according to whose thoughts:

“Selina was a girl in experience. She was a woman capable of a great deal of passion, but she did not know that. Passion was a thing no woman possessed, much less talked about. It simply did not exist, except in men, and then was something to be ashamed of, like a violent temper, or a weak stomach.”

But during one of their one-on-one math lessons, Selina’s passion becomes obvious, to herself at least.

Selina kept her eyes resolutely on the book. Yet she saw, as though her eyes rested on them, his large, strong hands. On the backs of them was a fine golden down that deepened at his wrists. Heavier and darker at the wrists. She found herself praying a little for strength—for strength against this horror and wickedness. This sin, this abomination that held her. A terrible, stark, and pitiful prayer, couched in the idiom of the Bible. “Oh, God, keep my eyes and my thoughts away from him. Away from his hands. Let me keep my eyes and my thoughts away from the golden hairs on his wrists. Let me not think of his wrists … A something in his voice—a note—a timbre. She felt herself swaying queerly, as though the whole house were gently rocking. Little delicious agonizing shivers chased each other, hot and cold, up her arms, down her legs, over her spine … “plus the square of the units is the same as the sum twice the tens … twice … the tens … the tens…” His voice stopped.

Selina’s eyes leaped from the book to his hands, uncontrollably. Something about them startled her. They were clenched into fists. Her eyes now leaped from those clenched fists to the face of the man beside her. Her head came up, and back. Her wide startled eyes met his. His were a blaze of blinding blue in his tanned face. Some corner of her mind that was still working clearly noted this. Then his hands unclenched. The blue blaze scorched her, enveloped her.

Her cheek knew the harsh cool feel of a man’s cheek. She sensed the potent, terrifying, pungent odor of close contact—a mixture of tobacco smoke, his hair, freshly laundered linen, an indefinable body smell. It was a mingling that disgusted and attracted her. She was at once repelled and drawn. Then she felt his lips on hers and her own, incredibly, responding eagerly, wholly to that pressure.

End of chapter. The next chapter begins “They were married the following May, just two months later.”

. . . . . . . . .

Barren Ground by Ellen Glasgow (1925)

Ellen Glasgow’s Barren Ground also portrays first-time sex in a poverty-stricken rural setting, this time in Virginia. Twenty-year-old Dorinda Oakley, working in a shop, falls in love with the doctor’s son Jason Greylock. He promises to marry her, though it would be against his father’s will, and neither of them have any money.

“After we’re married I can keep on in the store just the same.”

He laughed. “Ten dollars a month will hardly keep the fox from the henhouse.”

Bending his head he began to kiss; her in quick light kisses; then, as his ardor increased, in deeper and longer ones; and at last with a hungry violence. Though her love was the only thing that was vivid to her, she had even now, while she felt his arms about her and his lips seeking hers, the old haunting sense of impermanence, as if the moment, like the perfect hour of the afternoon, were too bright to endure. However much she loved him, she could not sink the whole of herself into emotion; something was still left over, and this something watched as a spectator. Ecstasy streamed through her with the swiftness of light; yet she never lost completely the feeling that at any instant the glory might vanish and she might drop back again into the dull grey of existence.

Like Mae, Dot, and Selina, Dorinda gets pregnant – the barren ground of the title turns out to be ironic. Dot’s and Selina’s men stay with them, Mae’s and Dorinda’s marry someone else – in Dorinda’s case because Jason’s father makes him.

He had wronged her; he had betrayed her; he had trampled her pride in the dust; and he had done these things not from brutality, but from weakness. If there had been strength in his violence, if there had been one atom of genuine passion; in his duplicity, she might have despised him less even while she hated him more.

Dot and Selina keep their babies. In Music in the Street, Mae tries unsuccessfully to have an abortion but in Barren Ground Dorinda goes to New York City looking for a better life. There she is knocked down by a cab in the street and miscarries; Dorinda is relieved.

She would have liked a child if it had been all hers, with nothing to remind her of Jason. For a second she had a vision of it, round, fair and rosy. Then, “it might have had red; hair,” she reminded herself, “and I should have hated it.”

The doctor who treats Dorinda subsequently employs her as a nurse for his children and asks her to marry him. She doesn’t, she wants something better. But after her father’s death, Dorinda returns to the farm and tries to bring fertility to its barren ground. Much later in her life, when she hears Jason has died, Dorinda feels ambivalent: she has never forgotten the first time though the scar has faded.

The passion that had ruined her life thirty years ago was nothing, was less than nothing, to her to-day. She was not glad that he was dead. She was not sorry that he had died alone … He had wasted his life, he had destroyed her youth; yet in a few hours death had thrown over him an aspect of magnanimity.

. . . . . . . . .

Cullum by E. Arnot Robertson (1928)

In E. Arnot Robertson’s first novel, Cullum, 1928, bookish Esther Sieveking wants to be a writer and loves books but no one around her does. British novelist Eileen Arbuthnot Robertson (1903 – 1961) published twelve novels (of which Cullum was the first) between 1928 and 1964 and wrote much film criticism. Virago republished three of Robertson’s early novels, including Cullum, in the 1980s.

Living in the country, among people who looked on books as a last resource for killing time when all other means had failed, I had never met anyone who cared at all for the things that I loved passionately.

Then into Esther’s sheltered village life comes the romantic figure of Cullum Cole, poet in the making, the son of a neighbor; they click straightaway and eventually become engaged, but they do not have any sexual relationship, or even any discussion of it. Unlike some other literary suitors of this time, Cullum is not constantly haranguing Esther about sex.

About halfway through the book, after much coming and going, Esther and Cullum become engaged. One day they go out together on a boat; coming back they “lounged on our bunks for some time, one on each side of the cabin, saying nothing, but enjoying the close companionship that follows shared physical exertion.”

They sit there for hours, “in this dim, most glorious night,” the two of them “utterly alone. I felt as if nature’s eternal sense of waiting had come to a breaking point of strain. Cullum’s hand, burning hot, closed over mine.” Esther moves away but he follows her and stands looking at her.

Desire in the eyes of the beloved man is the most wonderful sight earth holds for a woman.

“Esther, how beautiful you are!”

We both laughed shakily at nothing. He undressed, as I had seen him do often enough before, but there was a new glamour over everything that night. Cullum, stripped, was an unusually fine human creature. His body was one of those entirely beautiful things whose loveliness hurts. He was lithe, and the moulding of the long arms, lean and muscle-grooved, was splendid. Wide shoulders tapered down to narrow hips, set over narrow, deep thighs, and his fair skin held an almost transparent sheen.

He came over to me and instinctively I drew back, full of the happy fear of women. He caught hold of me and kissed my mouth, and throat, slipping the thin silk from my shoulders.

He let me go, and hesitated. “No, my dear, I –” and I held out my arms to him.

He took me then, and kissed me until my senses merged in a throbbing ecstasy of pain. All through the soft, warm darkness of that night we lay in each other’s arms, and slept a little, and woke to kiss and whisper, glorying in the wild, new, blinding wonder of love.

In the morning light we were shy with each other. “I say, Cullum,” I said, realizing the high-sounding fact with amusement, “are you aware that you are technically a seducer of innocent maidens? One maiden, anyway. How wonderfully sinister that sounds!”

“Doesn’t it! And you’re my victim!”

The idea struck us as supremely funny. It was impossible to think of Cullum in such a light, or of me, either.

. . . . . . . . .

Dusty Answer by Rosamond Lehmann (1927)

And finally, same-sex love, rather than sex, appears in a 1927 work by an English novelist, Rosamond Lehmann. The first lesbian novel is usually said to be The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall (1928) but Lehmann’s Dusty Answer precedes it by a year.

As in Hall’s novel, there’s no explicit lesbian sex, but a strongly implied relationship between two girls at college. Noted by outraged critics of the time, one of whom wrote an article in the London Evening Standard titled “The Perils of Youth,” addressing what he presumed to be the degenerate readers of Lehman’s novel:

To all these sex-ridden young men and women I would counsel, as the best remedy for their troubles, silence and self-control. And I would have them remember that all their discussions will never carry them back beyond the plain unvarnished statement of Genesis, “Male and female created He them.”

Lehmann herself said that the critics regarded her works as “the ravings of a nymphomaniac.”

Despite her crush on her friend Jennifer, Judith Earle first gives herself to a man, a childhood neighbor whom she meets again in later life:

Now the little boy Roddy was this tall man whose shoulder touching hers was more bewildering than the moonrise; whose head above hers was a barrier looking out the world… The web had broken. Roddy had shaken himself free and come close at last. The whole of their past lives had led them inevitably to this hour.

He put his hand beneath her chin and turned her face up to his.

“Lovely Judy. Lovely dark eyes . . . Oh your mouth. I wanted to kiss it for years.”

“You can kiss it whenever you want to. I’d love you to kiss me. All of me belongs to you.”

He muttered a brief “Oh!” Beneath his breath, and seized her, clasped her wildly. She could neither move nor breathe; her long hair broke from its last pins and fell down her back, and he lifted her up and carried her beneath the unstirring willow trees.

It seems as though Roddy has taken Judith’s virginity – or she has given it to him – under the willow trees but, as with Ferber’s So Big, it happens offstage, as it were, in a lacuna in the text; it is only implied here but she confirms it later on. Roddy does not love Judith and does not even want to see her after the incident but still she doesn’t regret it, such as it was.

It’s undoubtedly a coming of age moment for Judith, though not the final one. On the rebound, and only to hurt Roddy, she agrees to marry Martin, Roddy’s cousin and another of her childhood neighbors; he is very sweet and charming to her and loves her completely, but she can’t really see him as anything other than a childhood friend.

Then, while traveling, Judith meets Julian, the third of the cousins who used to live next door to her; he is now a world-weary, experienced, and cynical playboy who offers to make her his mistress, though he makes it clear he is not interested in marriage.

Julian must save her this time: surely his wit and wisdom, surely the unknown world of sexual, emotional and intellectual experience which he held so temptingly, just out of reach – surely these would, in time, heap an abiding mound upon the past.

But following the news of Roddy’s death, before she has chance to sleep with Julian, she changes her mind, falsely implying to him that she is still a virgin.

“Julian – I couldn’t give you – what you wanted. I couldn’t! It’s such a step – you don’t realize – for a woman. She can’t ever go back – afterwards, and be safe in the world. And she might want to.”

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie

is available on Amazon (US) and Amazon (UK)

. . . . . . . . . .

Related Content on Vera Caspary

- The White Girl by Vera Caspary, Forgotten Contemporary of Nella Larsen’s Passing

- Vera Caspary’s The White Girl and Other “Passing” Novels of the 1920s

- The Ultimate Caspary Woman: Laura by Vera Caspary

- Laura: The 1944 Film Based on the Novel by Vera Caspary

- Is Vera Caspary’s Bedelia the Wickedest Fiction Anti-Heroine?

. . . . . . . . .

See also: Pregnancy in Classic Novels by Women Authors

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

Leave a Reply