Vera Caspary’s The White Girl, and Other “Passing” Novels of the 1920s

By Francis Booth | On December 6, 2021 | Updated August 28, 2022 | Comments (0)

The White Girl by Vera Caspary (1929) bears comparison to several passing novels of the 1920s. “Passing” as white was a theme that fascinated authors of the 1920s, both within and outside of the Harlem Renaissance movement.

Following is an exploration of several 1920s novels of passing by Caspary and two by Jewish women writers like herself, as well as the renowned works of two Black authors of that era, Nella Larsen and Jessie Redmon Fauset.

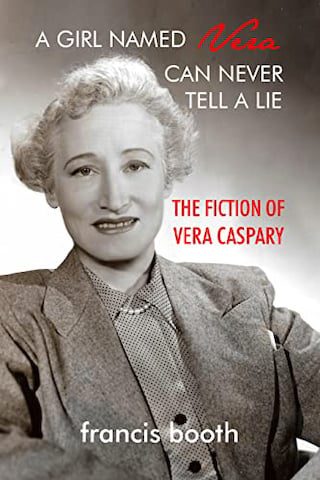

Excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

. . . . . . . . . .

The White Girl by Very Caspary (1929)

At the time she was writing The White Girl, Vera Caspary was also editing a dance magazine in New York and socializing with male Black dancers; she felt this gave her at least some credibility in writing this novel.

“I felt that my new friends could look through my pale flesh and see guilt. A word that hinted of flesh tints set me so on edge that I’d change the subject at once. They spoke easily of blacks and white people. One evening I sat with Pierce and a couple of his friends, telling jokes and speaking of many things, and suddenly he said, ‘Why, Miss Caspary, I forgot that you were white.’”

The model for Solaria, the central character in The White Girl was a girl Caspary had known at school, though only from a distance and an exotic figure for her.

“One day I had read in a newspaper an item about a black girl passing as white. The idea touched a vulnerable spot: guilt, unconscious until then, suddenly become an irritation. In my class at high school there had been a girl so lovely that I could never forget her, a quiet beauty with flesh as white and opaque as a camellia, flawless features, and eyes like sparkling jet. I had admired but never talked to her, never walked with her along the school corridor. Why? Why the aloofness, the pretense of blindness, the deaf ear to black classmates?”

Solaria, the central character in The White Girl, has a Black family and is very striking and attractive to men of all races; like Clare, she “passes” successfully.

“She was a tall girl with a languorous fine figure, small hips, exquisite breasts, and a narrow head carried high on a sensitive neck. Her wide-set dark eyes were dusky mirrors, mysterious, hardly alive. Her nose was straight and arrogant, set bravely above a short upper lip. With her fine black hair and white face, she looked as if she might be a Spanish aristocrat.”

After many trials, about midway through the story, Solaria is alone and constantly in debt, wondering why she did not marry the rich Black man in Chicago who wanted her so badly. “For the life of her she could not see what she had gained by passing.”

Solaria meets and falls in love with a moderately wealthy white man called David whose family is from snobby, ultra-white Scarsdale in Westchester County. She is constantly worried about her secret being uncovered.

Nella Larsen’s novel ends with tragedy as a result of Clare’s passing. Caspary had originally written an ending with what she called “a note of wry honesty.” The heroine, who had deceived and lost her lover had, like all working girls, to keep on with her job. But Caspary’s publisher didn’t like it and “wanted the story to end sensationally. Publishers and editors, I thought, must certainly be wiser than a young writer. I changed the ending.”

See an in-depth analysis of The White Girl in the context of Nella Larsen’s Passing.

. . . . . . . . . .

Passing by Nella Larsen (1929)

Passing by Nella Larsen was first published, like The White Girl, in New York in 1929, though a few months later. Larsen’s novel received more tepid reviews and fewer sales than Caspary’s, though both the settings and subject are quite similar.

In Larsen’s novel, Clare, whose father is a janitor (like Solaria’s in The White Girl), passes so successfully that her white husband never suspects she is Black until later on, when she reunites with an old friend who is involved in the (fictional) Negro Welfare League. Clare’s friend Irene has a Hispanic look.

“They always took her for an Italian, a Spaniard, a Mexican, or a Gypsy. Never, when she was alone, had they even remotely seemed to suspect that she was a Negro.”

Like Clare, their mutual friend Gertrude has married later a white man. Irene reflects:

“… though it couldn’t be truthfully said that she was ‘passing.’ Her husband—what was his name? — had been in school with her and had been quite well aware, as had his family and most of his friends, that she was a Negro. It hadn’t, Irene knew, seemed to matter to him then. Did it now, she wondered.”

Irene does not herself consciously try to “pass,” and she is curious about Clare and “this hazardous business of ‘passing,’ this breaking away from all that was familiar and friendly to take one’s chance in another environment, not entirely strange, perhaps, but certainly not entirely friendly.” When Clare asks Irene if she never thought of passing, Irene answers quickly “No. Why should I?”

For her part, Irene finds that her annoyance at women who try to pass “arose from a feeling of being outnumbered, a sense of aloneness, in her adherence to her own class and kind; not merely in the great thing of marriage, but in the whole pattern of her life as well.” Irene feels that she is betraying her race by helping Clare hide her origin from her husband, but is also reluctant to betray her friend in support of her race:

“… she shrank away from the idea of telling that man, Clare Kendry’s white husband, anything that would lead him to suspect that his wife was a Negro. Nor could she write it, or telephone it, or tell it to someone else who would tell him. She was caught between two allegiances, different, yet the same. Herself. Her race. Race! The thing that bound and suffocated her. Whatever steps she took, or if she took none at all, something would be crushed. A person or the race. Clare, herself, or the race. Or, it might be, all three.”

When her husband finds out, he accuses Clare of being a “damned dirty n–!” Clare falls out of the window and dies, though it isn’t clear whether she was pushed or if she has killed herself rather than carry on with her life after her racial heritage has been revealed. See a detailed analysis of Passing by Nella Larsen.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928)

Even closer to The White Girl than Passing is Jessie Redmon Fauset’s Plum Bun. Fauset, a talented student, was denied admission to Bryn Mawr because of her race. She went instead went to Cornell University and graduated in classical languages, then earned a Master’s degree in French at the University of Pennsylvania. Fauset was literary editor of the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, starting in 1919.

Plum Bun is also about a Black girl, Angela Murray, who is light enough to “pass,” and does so, even though her sister Virginia – like Solaria’s brothers in The White Girl – cannot. Like Solaria’s parents, Angela’s are proud of their race, and she is not.

“The stories which Junius and Mattie told of difficulties overcome, of the arduous learning of trades, of the pitiful scraping together of infinitesimal savings; would have made a latter-day Iliad, but to Angela they were merely a description of a life which she at any cost would avoid living. Somewhere in the world were paths which lead to broad thoroughfares, large, bright houses, delicate niceties of existence. Those paths Angela meant to find and frequent.”

Angela’s light-skinned mother also “passes,” but only part-time, and only as an amusement. To her it is simply a game:

“It was with no idea of disclaiming her own that she sat in orchestra seats which Philadelphia denied to colored patrons. But when Junius or indeed any other dark friend accompanied her she was the first to announce that she liked to sit in the balcony or gallery.”

Angela’s father is amused by and encourages his wife’s escapades: Junius “preferred one of his wife’s sparkling accounts of a Saturday’s adventure in ‘passing’ to all the tall stories told by cronies at his lodge.”

At school, Angela has a friend who seems unaware of her racial background. When the friend finds out about Angela she is outraged. “Colored! Angela, you never told me that you were colored!” At this age, Angela is still color blind and has no idea of the implications. “Tell you that I was colored! Why of course I never told you that I was colored. Why should I?”

After their parents die, Angela and her sister share the money from the house and the insurance money; both end up in New York City. Virginia embraces the life and people of Harlem; Angela stays downtown and enrolls in art college, still naïvely assuming her color will not be a barrier.

“She had not mentioned the fact of her Negro strain, indeed she had no occasion to, but she did not believe that this fact if known would cause any change in attitude. Artists were noted for their broad-mindedness.” Still, even Angela sees the attraction of Harlem, the camaraderie, the community, the richness and seething flow of life in a “walled city” where everyone is equal.

“Nowhere downtown did she see life like this. Oh, all this was fuller, richer, not finer but richer with the difference in quality that there is between velvet and silk. Harlem was a great city, but after all it was a city within a city, and she was glad, as she strained for last glimpses out of the lurching ‘L’ train, that she had cast in her lot with the dwellers outside its dark and serried tents.”

But downtown, Angela still feels constrained from making close friends while Virginia is living with her. “Two of the girls had asked her to their homes but she had always refused; such invitations would have to be returned with similar ones and the presence of Jinny would entail explanations.”

Angela then meets the very white, very wealthy Roger. “She had never seen anyone like him: so gay, so beautiful, like a blond, glorious god, so overwhelming, so persistent.” She sees that marrying Roger could be her ticket to the life she covets. “She saw her life rounding out like a fairy tale. Poor, colored—colored in America; unknown, a nobody! And here at her hand was the forward thrust shadow of love and of great wealth.”

Roger turns out to be a racist: while he is having a meal in a restaurant with Angela, Roger insists that the management expel a colored family. Angela finally sees him in his true colors. “He had blackballed Negroes in Harvard, aspirants for small literary or honor societies. ‘I’d send ’em all back to Africa if I could,’” Roger says to Virginia. It then turns out that he has no intention of marrying her but wants to set her up in an apartment as his mistress.

Angela does eventually “come out,” when she and another woman from the art college both win prizes to live in Paris. But the other woman is known to be “colored” and the prize is withdrawn on the grounds that other passengers on the boat to Europe may be offended by her presence.

Angela is outraged and reveals herself in sympathy, knowing that she will also lose her prize. However, both of them keep the money and Angela decides to go to Paris anyway, on her own. Before she goes, she is reconciled with her sister.

“All of the complications of these last few years, — and you can’t guess what complications there have been, darling child, — have been based on this business of ‘passing.’”

See another detailed analysis of Plum Bun by Jessie Redmon Fauset.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Show Boat by Edna Ferber (1926)

Like Vera Caspary, Edna Ferber was a Jewish woman author who began protesting against the rise of fascism early on, and also wrote sympathetically about race. Ferber’s Show Boat, 1926, better known as a musical and three films, isn’t about race specifically but does have a subplot concerning “passing.”

The characters in the novel all live on a showboat traveling up and down the Mississippi giving theatrical performances. Julie Dozier is one of the actresses, married to the actor Steve. Julie thinks no one knows that she had a Black mother and a white father, but someone has found out and told the local sheriff in the town where the boat is moored. It turns out to be one of the engineers who liked Julie and was upset when she would have nothing to do with him.

“Miscegenation. Case of a Negro woman married to a white man. Criminal offense in this state, as you well know,” says the sheriff when he boards the boat. But before the sheriff arrives, Steve, to everyone’s astonishment, has sliced a sharp knife through Julie’s forefinger.

“A scarlet line followed it. He bent his blond head, pressed his lips to the wound, sucked it greedily.” So when the sheriff says that, in Mississippi, “one drop of n– blood makes you a n– in these parts,” Steve is able to say truthfully, “Well, I got more than a drop of – n– blood in me, and that’s a fact. You can’t make miscegenation out of that.”

So, according to Mississippi’s racist laws, Steve is now Black because he literally has Negro blood inside him. The sheriff, however, is not impressed and makes sure the boat’s crew understands that if they go ahead with their performance that night there will be dire consequences. “You go to work and try to give your show with this mixed blood you got here and first thing you know you’ll be riding out of town on something don’t sit so easy as a boat.”

The other actress on the boat, Elly, who is the very white, racist “ingénue lead,” screams at Julie, “The wench! The lying black –” Elly threatens to leave if Julie doesn’t, and Ferber, as her author, makes clear her own views on racism: vile, obscene, and ugly.

“She gets out of here with that white trash she calls her husband or I go, and so I warn you. She is black! She is black! God, I was a fool not to see it all the time. Look at her, the nasty yellow –” a stream of abuse, vile, obscene, born of the dregs of river talk heard through the years, now welled to Elly’s lips, distorting them horribly.

The rest of the crew is sympathetic, and the central character, Magnolia, young as she is and never having known any life other than that of the boat, knows where she stands: Magnolia says to the sheriff, “You’re a bad mean man, that’s what! You called Julie names and made her look all funny. You’re a –”

At this point her mother stops Magnolia from going any further. Still, despite their sympathy, the crew knows that Julie and Steve cannot stay; they leave the boat with dignity, transcending the racism they leave behind. “Julie’s slight figure was bent under the weight of the burden she carried. You saw Steve’s fine blond head turned toward her, tender, concerned, encouraging.”

Read more about Showboat by Edna Ferber.

These are just four of many novels written by both Black and white authors, female and male, about racial identity and passing in the 1920s. Other notable works in this genre by male authors include Cane by Jean Toomer (1923) and The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson. The latter was first published anonymously by a small press, then reissued in 1927 by Alfred A. Knopf, when Johnson had already achieved major stature as a civil rights leader and literary figure.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie

is available on Amazon (US) and Amazon (UK)

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture: Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

Leave a Reply