The Ultimate Caspary Woman: Laura by Vera Caspary

By Francis Booth | On November 2, 2021 | Updated April 8, 2022 | Comments (0)

Laura, a detective novel/murder mystery published in 1943, has remained Vera Caspary’s best-known work, partially thanks to the well-regarded film adaptation that followed. The slim yet action-packed story was first serialized in Collier’s magazine in 1942 as Ring Twice for Laura.

In the excellent afterword for the 2005 Feminist Press edition of this book, A.B. Emrys writes:

“Caspary’s fairy tale for working women takes place in a world of men who use women for advancement and self-reflection. The potential darkness of this world places Laura into the noir category and shadows even Caspary’s non-crime fiction … ‘Who can you trust’ was a game working women had to play frequently, and Laura makes evident that women might be labeled femmes fatales because they worked in the male-dominated business world.”

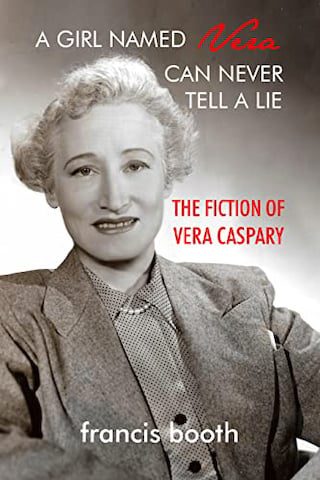

Though Laura is sometimes classified in the femme fatale genre, this isn’t accurate. The eponymous heroine is a smart, hardworking, independent woman (her dicey taste in men aside), and the prototype for the ultimate Caspary woman. The following discussion of Laura is excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

Laura turned detective fiction on its head. In most mid-twentieth century women’s crime novels, the central character is a male detective: Marjorie Allingham’s Albert Campion; Margaret Millar’s Paul Prye, Inspector Sands and Tom Aragon; Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey; Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot (Miss Marple is an exception); Ngaio Marsh’s Inspector Alleyn.

They were all working in a tradition started in 1878, ten years before Sherlock Holmes first appeared, by Anna Katharine Green, the “mother of detective fiction” with her series of detective Ebenezer Bryce novels. If Philip Marlowe is the Chandler man, Laura introduces the Caspary woman.

“She is carved from Adam’s rib, indestructible as legend, and no man will ever aim his malice with sufficient accuracy to destroy her.”

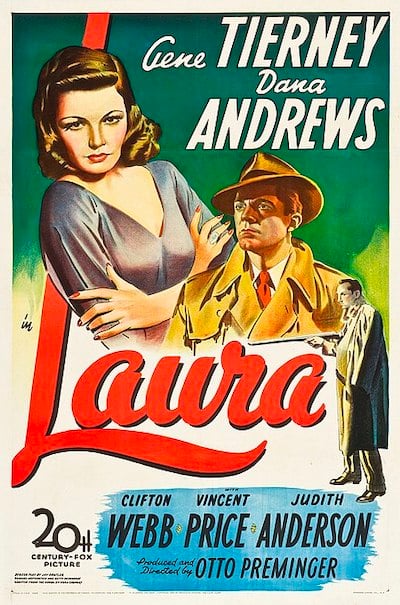

This is from the final sentence of Laura, Vera Caspary’s fifth novel, her first major commercial success. It has remained her most famous and popular work, as a novel and as well as the 1944 film adaptation.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vera Caspary

Learn more about Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . .

Enter the Caspary Woman

Laura is the first of a series of thrillers in which the Caspary woman appears, bursting onto the page here as a fully formed heroine for her time. Caspary much later described this woman in her autobiography:

“I’d given Laura a heroine’s youth and beauty but had added the strength of a woman who had, in spite of the struggle and competition of success in business, retained the feminine delicacy that allowed men to exercise the power of masculinity.”

Laura Hunt, as the first Caspary woman, would have several successors in Caspary’s works but very few in the works of other writers, even female ones; Laurel Grey in Dorothy B. Hughes’ 1947 In a Lonely Place is an exception. Laurel (as filtered through the viewpoint of the male anti-hero) was “a dream he had not dared dream, a woman like this. A tawny-haired woman; a high-breasted, smooth-hipped, scented woman; a wise woman.”

Laura is groundbreaking for its title, which unambiguously points to a woman as being the focus of the novel rather than the solving of a crime. Very few mid-twentieth century novels of any genre had just a woman’s name as the title – Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), though the title character is dead and doesn’t appear in the novel in person.

The genesis of Laura

Caspary had never written a murder mystery in the form of a novel before Laura and had not been particularly inclined to do so because character has to give way to plot in a crime novel.

“Mysteries had never been my favorite reading. The murderer, the most interesting character, has always to be on the periphery of action lest he give away the secret that can be revealed only in the final pages.”

A murder mystery as a screenplay was an easy thing for her but a novel was something completely different. In her 1979 autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups, Caspary talks about the genesis of Laura:

“Most of my originals had been murder stories, but I never thought of them in the same class as a novel. The novel demands a full development of each character. This was my problem. Every character in the story, except the detective, was to be a suspect—particularly the heroine, with whom the detective was to fall in love.

If her innocence was in doubt, how could her thoughts be made clear to the reader? I did not want to cheat. If she and the other characters were to be made more than detective-story stereotypes, I had to find a way to show them alive and contradictory while keeping secret the murderer’s identity.

The story fascinated my friend Ellis St. Joseph, who suggested that I try the Wilkie Collins method of having each character tell his or her own version, revealing or concealing information according to his or her own interests. Night after night Ellis and I sat up talking about Waldo Lydecker, the impotent man who tries to destroy the woman he can never possess.

We developed his background, imagined his youth, analyzed the causes of his frustrate masculinity, considered his taste, his talent, his idiosyncrasies. I enjoyed the trick of writing in his style, contrasting his florid mannerisms with the direct prose of the detective and, through the girl’s version, showing the vagaries of the female mind. After all those barren mechanical years, I worked with the zest of a young writer with a first novel.

Sometime in October it was finished. In order to see the story objectively I needed time away from obsession. Paramount offered a job and I went to work on a story about a night plane to Chungking. War interrupted. . .

I returned happily to reworking my mystery. On Christmas morning I wrote ‘The End’ and, on the title page, Laura. At dinner my friends toasted the book. Indeed it was a splendid holiday, the start of a new career and a year that was to change my life. I had come to California for three months; I stayed twenty-four years.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Laura by Vera Caspary on Bookshop.org* and Amazon*

. . . . . . . . . .

Multiple points of view

Laura does indeed employ multiple points of view, being narrated at first by the effete aesthete Waldo, who we initially assume is going to be the central character.

Waldo’s first-person narration is followed by a section of narration in the third person with Waldo as the informing intelligence, and then by sections narrated by the detective Mark McPherson, an interlude of stenographic reports of interviews at the police station and narrations by Laura herself.

But, hang on, how can Laura speak? She’s dead? Isn’t she?

No, she isn’t, as it turns out. At first, we are meant to think that Laura Hunt is like Rebecca, the absent titular heroine who overshadows everything and everyone from beyond the grave.

But, after “her” funeral, Laura returns and we find out that the dead body lying in the doorway of Laura’s apartment with her face blown away by the shotgun was not Laura at all but Laura’s friend Diane, wearing her robe; she had been staying in Laura’s apartment while Laura was away.

Not that Diane was much of a friend anymore: she had stolen Laura’s boyfriend Shelby, making Laura the prime suspect in her murder. This is quite a twist: the murdered woman is not the murdered woman but the putative murderer of another woman.

From echoing Rebecca, Laura suddenly turns into Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, 1859, with which it has many deliberate parallels, including the name of its title character. In Collins’ novel, the two young women Anne and Laura’s identities are switched after Laura refuses to give up her marriage settlement of twenty thousand pounds. Anne then dies of her long-term illness and is buried as Laura; Laura is considered mad for claiming to be Laura and is locked up.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie on Amazon (US)*

and Amazon (UK)*

. . . . . . . . . .

Waldo Lydecker

Caspary’s physical description of Waldo Lydecker came straight from Count Fosco in The Woman in White; this sentence describing Fosco could just as well be in Laura.

“Fat as he is and old as he is, his movements are astonishingly light and easy. He is as noiseless in a room as any of us women, and more than that, with all his look of unmistakable mental firmness and power, he is as nervously sensitive as the weakest of us. He starts at chance noises as inveterately as Laura herself.”

Everything in the description of Waldo that Caspary worked so hard on with Ellis St. Joseph – his exquisite taste, his apartment, his cane, his Filipino houseboy, his erudite, witty, and rather camp writing style – scream to the contemporary reader, and perhaps to the sophisticated reader in 1945, that Waldo is gay.

But, as we saw, according to Caspary’s much later description in her autobiography, Waldo is intended as an “impotent man who tries to destroy the woman he can never possess,” namely, Laura. Waldo is a beautifully drawn character: a famous reviewer, columnist and essayist, waspish and withering, a society butterfly.

If we have not read Caspary’s autobiography, we will assume that Waldo loves Laura, with whom he has had a close relationship for several years, in a nonsexual way, that it is good for him as a gay man to be seen about town with a beautiful young woman – lavender marriages were very common at the time in high society, especially in Hollywood

For her part, Laura is happy to be in the company of somebody much older, a wealthy, cultured man who is no threat, intended to keep away the attention of younger, eligible men. It does strike rather a sour note when, towards the end, we find out that Waldo’s love for Laura was nowhere near platonic, though we may remember that at the beginning of the book Waldo has said, “I offer the narrative, not so much as a detective yarn as a love story.”

. . . . . . . . . .

The sensationalized pulp cover

. . . . . . . . . .

Shelby and Diane

But, despite her affection for Waldo and the amount of time she spends with him, Laura does have a boyfriend, the rogue Shelby Carpenter, a louche lounge lizard and something of a playboy.

We are not too surprised to find out later that Shelby has been having an affair with the late Diane and possibly even with Laura’s wealthy aunt Susan – a Caspary woman herself, with no man in sight, a summer place on Long Island and a big house on Fifth Avenue – despite Susan’s northerner’s snobbery about southern men.

Laura works in advertising, in a role not entirely unlike Caspary’s own jobs in copywriting. She is very successful at it – the Caspary woman is always a success in business and Laura does very well financially, much better than Shelby, who has a very loose work ethic. Caspary women tend to be more ambitious and earn more than the men they associate with; the men tend to have something of a problem with this.

Laura’s career and earning potential are also contrasted to those of the detective Mark, who says to Waldo, “I’m a workingman, I’ve got hours like everyone else. And if you expect me to work overtime on this third-class mystery, you’re thinking of a couple of other fellows.”

Also contrasting with Laura is the now-deceased Diane, who is not at all the typical Caspary woman. Her shabby downtown apartment is starkly contrasted with Laura’s swanky but discreet place up on East 66th Street in Manhattan.

Despite the exorbitant rent on her remodeled third-floor apartment with a garden, unheard of in Manhattan (though Caspary woman Sara in Murder at the Stork Club has one; she also has a PI husband who earns a lot less than she does), Laura “had lived here, she told me, because she enjoyed snubbing Park Avenue’s pretentious foyers.”

She has her own key to the door at street level, which is essential to the plot: if she had lived in a doorman apartment, the killer would have been seen. In Diane’s very different fourth floor apartment in the West Village there is the added subtle class distinction that Diane paid cash in stores rather than having an account, as any true Caspary woman would.

Detective Mark’s turn

Mark inspects her apartment, trying to pin down her character. He does, as superbly and succinctly encapsulated in Caspary’s writing:

“There were no bills as there had been in Laura’s desk, for Diane came from the lower classes, she paid cash. The sum of it all was a shabby and shiftless life. Fancy perfume bottles, Kewpie dolls, and toy animals were all she brought home from expensive dinners and suppers in night spots. The letters from her family, plain working people who lived in Paterson, New Jersey, were written in night-school English and told about layoffs and money troubles. Her name had been Jennie Swobodo.”

As Laura is one of Caspary’s alter egos, so Diane is the other. Caspary talked in her autobiography of the “skinny girl” of her imagination, the girl who represents the other side to her public persona.

Detective Mark, speaking in his hard-boiled, noir mode says of the deceased, purely based on seeing her apartment, “I had known girls like that around New York. No home, no friends, not much money. Diane had been a beauty, but beauties are a dime a dozen on both sides of Fifth Avenue between Eighth Street and Ninety-Sixth.”

Both apartments are contrasted with the elegance and refinement of Waldo’s, filled as it is with the most refined and exquisite antiques.

“Everything he owned was special and rare. His favorite books had been bound in selected leathers, he kept his monogrammed handkerchiefs and shorts and pajamas in silk cases embroidered with his initials. Even his mouthwash and toothpaste had been made up from special prescriptions.”

Laura claims, when suspected of murdering Diane out of jealousy, not to have been upset by Diane’s relationship with ostensibly perfect Kentuckian gentlemen Shelby, even though Laura and Shelby were to have been married just a few days after the murder. Laura herself claims to have come from a poor background, though this seems unlikely in light of her aunt’s Fifth Avenue brownstone.

“I’m not so different. I came to New York, too, a poor kid without friends or money. People were kind to me . . . and I felt almost an obligation toward kids like Diane. I was the only friend she had. And Shelby.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Laura — the 1944 Film Based on the Novel by Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . . .

Motives and simmering jealousy

In a Caspary woman gender reversal, Laura has given Shelby an extravagant cigarette case, “fourteen-karat gold, as a man might buy his wife an orchid or a diamond to expiate infidelity.” Normally the giver is the unfaithful one, but not Laura. Shelby has given the precious object to Diane – surely not something a true southern gentleman would do.

Diane has pawned it and Laura has found out, giving her ample motive for the murder of Diane. Meanwhile, Mark the detective has developed more than a professional interest in Laura – and vice versa. Waldo is outraged, he tries to make Laura understand how a man like Mark sees women: he cannot truly appreciate them.

“Do you know Mark’s words for women? Dolls. Dames.” Waldo, connoisseur of women as of all things aesthetic, sneers to her, “What further evidence do you need of a man’s vulgarity and insolence? There’s a doll in Washington Heights who got a fox fur out of him—got it out, my dear, his very words. And a dame in Long Island whom he boasted of deserting after she’d waited faithfully for years.”

Waldo also tries to persuade Mark that he is mad to pursue Laura, who is completely out of his league. But Mark’s obsession makes him blind to the fact that any true Caspary woman will always be beyond his reach.

Laura is indeed no dope and is not at all bound by the shackles of romance, but, “going on thirty and unmarried, I had become alarmed,” and bought Shelby the cigarette case, “pretending to love him and playing the mother game.”

For Laura, as a true Caspary woman, gender roles are inverted: the handsome, debonair Shelby was to be a trophy husband; the fact that her friend pursued her fiancé simply reinforced the triumph of the trophy.

Laura thinks of Shelby as a child, exactly in the way a stereotypical male character in a novel by a male writer might think of his stereotypical trophy wife. “I was afraid because I had always been weak with a thirty-two-year-old baby.”

Interestingly, since Caspary says in her autobiography that she enjoyed playing with the different styles of narration it is surely not a coincidence that the sections narrated by Laura are better written, with finer, more “novelistic” writing than the others.

But, though only Laura and no one else appears to have a motive for murdering Diane, Shelby also has a motive for murdering Laura. Mark and everyone else assume that Diane was shot by mistake when she answered the door in Laura’s robe while staying at Laura’s apartment, but what if she wasn’t? What if Laura was the target?

In a gender-reversed pre-echo of the plot driver in Bedelia there is a twenty-five thousand dollar insurance policy that Laura has made over to him. Shelby has a shotgun, as any southern gentleman would, so he has means as well as motive and opportunity.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:

Is Vera Caspary’s Bedelia the Wickedest Fictional Anti-Heroine?

. . . . . . . . . .

Questions to be answered — without spoilers!

Was it then Laura, the Caspary woman who expects the same rights as men, who wanted sex from a relationship, and Waldo who was unable to give it? Did she turn to Shelby to satisfy her physically?

And was Shelby driven to Diane because he was scared of Laura, unable to satisfy a woman who was smarter than him and earned five times as much as he did? None of these things could be said out loud in 1942.

And then, what happens after the ending of the novel? Does Laura go ahead and marry Shelby, or does Mark take his place? We have to hope not: Mark would never cope with her, she would destroy him. Mark, with his dolls and dames and police cronies, would never understand the Caspary woman.

More information

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . . .

*These are Bookshop Affiliate and Amazon Affiliate links. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Leave a Reply