Vera Caspary, prolific novelist and screenwriter

By Nava Atlas | On February 16, 2022 | Updated July 30, 2024 | Comments (0)

Vera Caspary (1899– 1987) was a remarkably prolific American novelist, screenwriter, and playwright. Over the course of her long career, she became known as a writer of crime fiction, though she created works in other genres.

With more than twenty novels published (plus others left unpublished), the best known remains Laura (1943). She also wrote long short stories and novellas, not to mention numerous screenplays for Hollywood films, some based on her own works.

Many of her works featured young, forward-thinking women (then called “career girls”) who fought for female autonomy and equality, and refused male protection.

According to her autobiography, Vera considered herself lucky to have lived during the “century of the woman,” and to have been part of the struggle that led to greater equality. Her work paved the way for the strong female characters we celebrate in contemporary fiction, and her own life story serves as inspiration for women who strive for equality today.

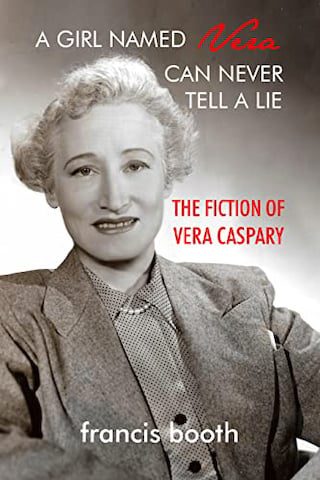

Francis Booth, the author of A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie (the first work to examine all of Caspary’s novels) observed:

“Although she worked in Hollywood and many of her novels were published as pulp paperbacks with lurid covers and sensationalist blurbs, Caspary herself was a connoisseur of classic British literature. One Caspary woman calls herself Haworth after the Brontë Parsonage, Stranger Than Truth pays homage to Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White and Bedelia to Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret.”

Education and the start of a writing career

Vera Caspary was born into a middle-class family Jewish family in Chicago, the youngest of four children. Enjoying a happy childhood, she attended public schools in Chicago and graduated from high school in 1917.

After completing a six-month course in business, she worked in a variety of office jobs. She was a stenographer, a copywriter, and served as director of a correspondence school that offered ballet lessons.

Vera began working on her first novel in 1922. After the death of her father in 1924, she moved to New York to work as the editor of Dance Magazine, a position she held from 1925 through 1927.

First novels

In 1929, Vera released her second novel, The White Girl. It tells the story of a young mixed-race woman who “passes” as white. Vera’s next novels, published later the same year, were Ladies & Gents and Music in the Street. The latter was inspired by the time she spent living in a home for working girls.

In 1931, Vera moved back to Chicago. Together with playwright Winifred Lenihan, she wrote a play called Blind Mice. The play was the inspiration for Working Girls, a film that was released in December 1931. The following year, Vera published a novel of the same name. Her family members were characters in the story, and they appeared with invented names.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

A sojourn in Hollywood

Vera had been supporting her mother with the money she earned from writing, so at this point in her life, she was almost penniless. After a chance meeting with an editor at Paramount, she wrote “Suburb,” a 40-page story that earned her two thousand dollars. The money was enough to enable her to move to Hollywood, where she wrote plays with Samuel Ornitz.

After winning a six-month writing contract with Hollywood studios, Vera had a falling out with Harry Cohn, the founder of Columbia Pictures. Though she still had five months left on her contract, she no longer received assignments, and instead spent her days at the beach. Eventually, she was able to get her contract canceled, and returned to New York.

Introduction to Communism

In the 1930s, many writers were interested in socialism, and Samuel Ornitz gave Vera copies of The Communist Manifesto and The Daily Worker. Eventually, Vera joined the Communist Party. “Lucy Sheridan” was her alias, and she hosted fundraisers and Party meetings at her home. However, she later stated that she was not fully committed to communism.

In 1939, she went to Russia to see communism in action. Upon her return to New York, she tried to resign from the Communist Party and was given a leave of absence. In January of 1940, she moved back to Hollywood.

. . . . . . . . . .

The sensationalized pulp cover of Laura

. . . . . . . . . .

Breaking through with Laura

In October 1941, Vera completed Laura, the breakthrough work that would become her most famous novel. A very different kind of detective novel, it centers on the presumed murder of the title character and the hunt for her killer. Told in the first person by different characters, it’s particularly noteworthy for its surprising twist. Like the title character, Vera was a strong, independent woman who had worked in the male-dominated world of New York advertising.

Laura debuted in serial installments in Collier’s magazine from November through December 1942. Vera wrote a dramatization of it that same year. Published in book form by Houghton Mifflin in 1943, Laura was released as a film in 1944. Directed by Otto Preminger, it is considered a film noir classic.

Meeting Isadore “Igee” Goldsmith

In addition to her professional breakthroughs, Vera’s personal life underwent significant change in the 1940s. She met her future husband, Isadore Goldsmith (“Igee”), in 1942. Igee worked as a film producer. After she returned home from a business trip to New York, he was waiting for her with red roses.

Sadly, their time together was cut short. As a British citizen, Igee was drafted for service in World War II and was compelled to return to England. He and Vera wouldn’t see one other again for thirteen months.

While Igee was away, Vera began working on her next novel, Bedelia. As a way to reunite with Igee, Vera cabled him in late 1944 to offer him the film rights for a British screenplay of Bedelia, on the condition that she could come over to England to write it. She arrived in England in January 1945 and spent several months there with Igee before returning to the U.S.

In 1946, Stranger Than Truth, a novel, and The Murder in the Stork Club, a novella, were published. She and Igee were reunited in May 1946, and they married on October 5, 1949. Vera was just shy of fifty years old, and it almost goes without saying that the couple didn’t have children.

The late 1940s saw the release of A Letter to Three Wives, a film considered a classic.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie

is available on Amazon (US) and Amazon (UK)

. . . . . . . . . .

The 1950s and Later Life

In 1951, Vera was questioned by MGM about her communist ties. Fearing that she’d be blacklisted, she fled to Europe with Igee, where they lived happily in a fairytale castle in Austria; Vera wrote contentedly in a tower room, including a draft of Wedding in Paris, her only musical comedy for the stage.

1953 saw the release of the film Blue Gardenia, directed by Fritz Lang, based on Vera’s story, “The Gardenia.” It has stood the test of time as a classic of the era.

Vera was placed on the “gray list” (which was somewhat less dire than the dreaded blacklist), and she and Igee did not return to Hollywood permanently until 1956.

In 1957, Vera wrote the screenplay for Les Girls. The film starred Gene Kelly, and Vera remembered the production as one of her most enjoyable experiences. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, she published several novels, including The Husband, Evvie, and Bachelor in Paradise.

Sadly, Igee was diagnosed with lung cancer in the early 1960s. Between surgeries and other treatments, he and Vera traveled to Greece, Las Vegas, and many of the places they’d meant to visit. Igee passed away in Vermont in 1964. After his death, Vera returned to live in New York.

From 1964 through 1979, Vera published eight books. The Secrets of Grown-Ups, her memoir, was published in 1979. After suffering a stroke, Vera passed away in New York in June 1987.

. . . . . . . . . .

Is Bedelia Fiction’s Wickedest Anti-Heroine?

. . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Vera Caspary

As Vera wrote in her memoir, “In another generation, perhaps the next, equality will be taken for granted. Those who come after us may find it easier to assert independence, but will miss the grand adventure of having been born a woman in this century of change.”

In recent times, Caspary’s works have been republished, albeit a fraction of her output, by the Feminist Press and the Murder Room. Francis Booth writes, “In her thrillers and murder mysteries, Caspary tackled sexism, racism, fascism and anti-Semitism head-on, from her first novel in 1929 to her last in 1975.”

Through her unconventional life and the independence of her characters, Vera Caspary redefined “the grand adventure” of living as a modern woman. She inspired women to live life on their terms, and she continues to inspire women to make bold choices to this day.

A few quotes by Vera Caspary

“This has been the century of the woman, and I know myself to have been a part of the revolution.” (from The Secrets of Grown-Ups)

. . . . . . . . .

“She is carved from Adam’s rib, indestructible as legend, and no man will ever aim his malice with sufficient accuracy to destroy her.” (from Laura)

. . . . . . . . .

“All my tales, whether gaily caparisoned with wealth or morbid in poverty, whether celebrating health or pain (for there are sanatoria and cemeteries as well as ballrooms), tell of man’s reliance upon woman, his need, blindness, and final recognition. In its many beginnings, mutations, and styles of narration, my story always concerns man’s search for the sympathy and satisfaction that only the heroine can bestow.” (from Evvie)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“In its many beginnings, mutations and styles of narration, my story always concerns man’s search for the sympathy and satisfaction that only the heroine can bestow.” (from Evvie)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“I am a chosen sparrow. And even one small bird can keep the guilty from peaceful slumber through the haunted nights.” (from A Chosen Sparrow)

. . . . . . . . . . .

“The real villain of the tale is Cinderella, with her absurd persistence in maintaining the legend that unless we are richly kept, we are failures as women.” (from Thelma)

More about Vera Caspary

On this site

Novels and short stories

Follow this link for Vera Caspary’s full bibliography.

- 1929 The White Girl

- 1929 Ladies and Gents

- 1929 Music in the Street

- 1930 Anyone Can Wear Pink

- 1932 Thicker Than Water

- 1942 Laura

- 1943 Sugar and Spice

- 1943 Stranger in the House

- 1945 Bedelia

- 1945 Murder at the Stork Club/The Lady in Mink

- 1946 Stranger Than Truth

- 1947 Out of the Blue

- 1948 Marriage ‘48

- 1950 The Weeping and the Laughter/Death Wish

- 1952 Thelma

- 1952 The Gardenia

- 1954 False Face

- 1957 The Husband

- 1960 Evvie

- 1961 Bachelor in Paradise

- 1964 A Chosen Sparrow

- 1966 The Man Who Loved His Wife

- 1967 The Rosecrest Cell

- 1968 Ruth

- 1971 Final Portrait

- 1975 The Dreamers

- 1978 Elizabeth X/The Secret of Elizabeth

Memoir

- The Secrets of Grown-Ups (1979)

Filmography

- 1931 Working Girls (from the play Blind Mice)

- 1932 The Night of June 13 (from the unpublished story “Suburb”)

- 1934 Private Scandal (from the unpublished story “In Conference”)

- 1934 Such Women Are Dangerous (from the unpublished story “Odd Thursday”)

- 1935 I’ll Love You Always (screenplay)

- 1937 Easy Living (based on her story)

- 1938 Scandal Street (from the unpublished story “Suburb”)

- 1938 Service de Luxe (based on her story)

- 1940 Sing, Dance, Plenty Hot (based on her story)

- 1941 Lady from Louisiana (screenplay)

- 1943 Lady Bodyguard (based on her story)

- 1944 Laura (from her novel)

- 1946 Claudia and David (adaptation)

- 1946 Bedelia (screenplay from her novel)

- 1947 Out of the Blue (screenplay from her novel)

- 1949 A Letter to Three Wives (adaptation)

- 1950 Three Husbands (screenplay from her story)

- 1951 I Can Get It for You Wholesale (adaptation)

- 1953 The Blue Gardenia (from her story “The Gardenia”)

- 1953 Give a Girl a Break (from her story)

- 1955 A Portrait of Murder (20th Century-Fox Hour TV hour episode from her novel Laura)

- 1957 Les Girls (from her story)

- 1961 Bachelor in Paradise (from her novel)

- 1962 Laura (TV Movie from her novel)

- 1968 Laura (TV Movie from her novel)

- 1985 A Letter to Three Wives (TV Movie adaptation)

More information and sources

- The Secrets of Vera Caspary, the Woman Who Wrote Laura

- Jewish Women’s Archive

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Dolls and Dames — Laura by Vera Caspary

- The Broadcast 41

Leave a Reply