4 Fearless American Female Newspaper Publishers of the 1800s

By Nava Atlas | On March 16, 2020 | Updated May 12, 2025 | Comments (0)

For a small number of American female journalist-reformers of the 1800s, starting their own newspapers became a matter of necessity. Refused the opportunity to report on matters of importance by male-dominated mainstream newspapers, they took matters into their own hands.

Launching their own newspapers became platforms for raising awareness of the justice issues they fought for.

Anne Newport Royall, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, and Jovita Idár are no longer familiar names; Ida B. Wells (pictured above right) might be better known to those interested in Black history. But all deserve to be better known and deserve a place of honor as publisher-reformers in an era when women’s voices were more often silenced than heard.

Fighting for the right to report

Even before women began fighting for the right to vote, they fought for the right to report. Women journalists wore their independence proudly, often refusing to conform to gender roles and society’s random limits for women.

In the 1800s, the few women who managed to step inside the world of newspaper work at all were often steered to writing about society, fashion, and domestic topics.

Those who wanted to report on hard news and social justice issues were usually thwarted. For a few undaunted women, there was just one remedy —to publish newspapers of their own.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

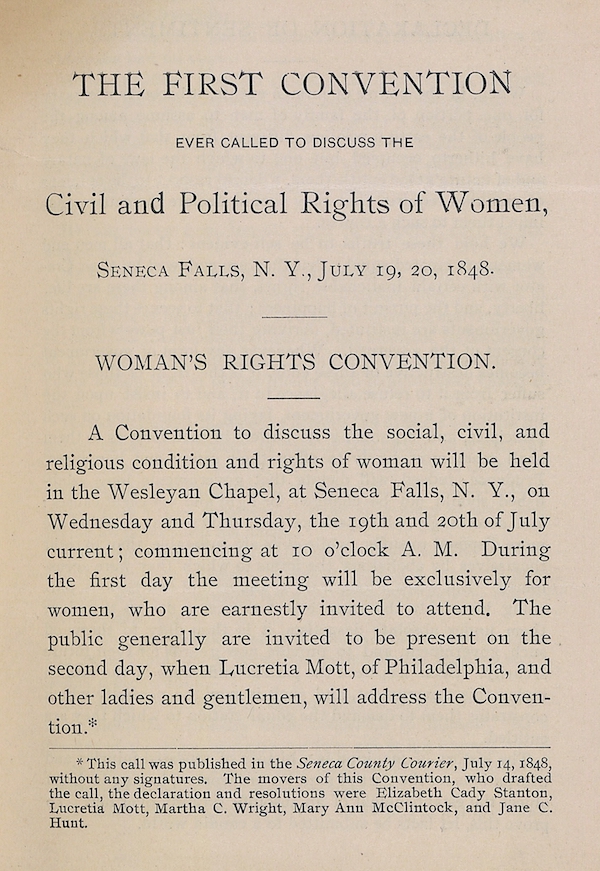

Seneca Falls Convention, 1848 — a turning point

The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 proved to be something of a national turning point for American women. It was the first national event devoted to waking women up to their second-class citizenship.

Husbands and fathers controlled the lives of wives and daughters; females couldn’t own property or sign contracts; and of course, they couldn’t vote. Job prospects were mainly limited to poorly paid service and domestic work or teaching.

At the same time, the issue of slavery was tearing the country apart. Many of the same people (both male and female) involved with women’s rights were also involved in the abolition movement. Journalists often crossed paths and pens working for these causes and writing for anti-slavery and pro-women newspapers.

Reform-minded journalists

Following the Civil War, the slavery question may have been legally settled, but life for African-Americans continued to be challenging, if not downright dreadful. The women’s rights movement was in full force, but progress was painfully slow.

Reform-minded journalists weren’t willing to wait for permission to report on the injustice woven into every aspect of American life — civil rights, women’s rights, labor, immigration, education, and more.

Though women who started newspapers were few and far between, the listing that follows is by no means a complete overview. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, for example, started and ran the women’s suffrage newspaper, The Revolution, from 1868 to 1872. But their names live on in the American consciousness. And you can read about Victoria Woodhull and The Weekly, a radical reform newspaper she launched with her husband and sister.

Here we focus on four women newspaper publishers who aren’t as well known today. Their lives and the spirit of the work they did deserve to be remembered and honored today, as they blazed trails for today’s female journalists and publishers.

. . . . . . . . .

Anne Newport Royall (1769 – 1854)

“Free thought, free speech, and a free press!” That was the rallying cry of Anne Newport Royall, considered America’s first female journalist. Growing up impoverished and fatherless, she started her youth and adult life as a domestic servant.

Her writing career was launched later in life with a series of books filled with colorful accounts of southern states and territories. That made her a pioneering travel journalist, and she also broke ground as a political and investigative reporter.

Always poor and forever struggling, Anne used all of her resources to start a newspaper. She was in her early 60s when she launched it in 1831 under the odd name Paul Pry. Later, she updated the name to The Huntress. There are no existing images of Anne Newport Royall, so we have to be content with an advertisement for Paul Pry, above.

In her own words, the paper was “dedicated to exposing all and every species of political evil and religious fraud, without fear or affection.”

Indeed, publishing her paper was hard going. It was written of her venture that “snow sometimes covered the floor where her paper was printed and the ink froze before it could record her blistering phrases.”

Anne was feared and scorned by Washington, D.C.’s powerful men — politicians, businessmen, and religious leaders — who dreaded seeing their names in her newspaper. But she dared to publish the truth. She was even convicted of being “a public scold” — which was actually a crime at the time!

Pushed down flights of stairs, beaten about the head, and ducking rocks thrown through her windows, nothing stopped her and no one intimidated her. She continued to publish The Huntress until she drew her last breath at age eighty-five, in 1854. It was all the more remarkable that she accomplished much of what she did before women officially began agitating for rights in the mid-19800s.

. . . . . . . . . .

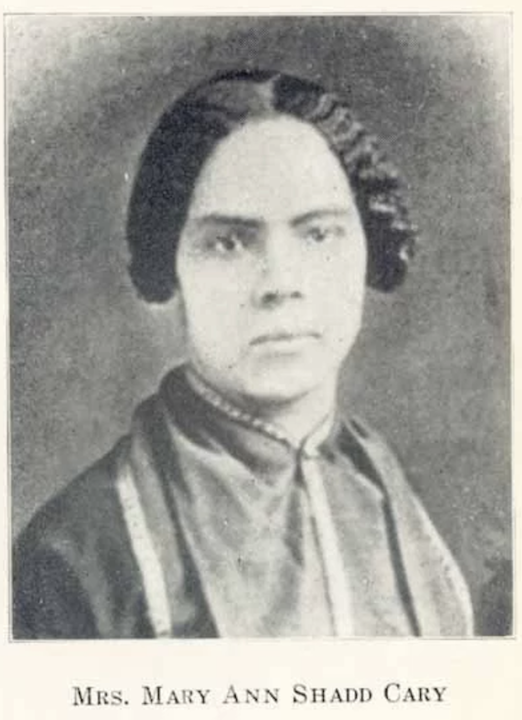

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823 – 1893)

Mary Ann Shadd (later adding the name Cary when she married) was the proverbial apple who didn’t fall far from the tree. Growing up as the oldest of thirteen siblings in a close-knit free Black family, she was deeply influenced by her parents’ devotion to equality. The Shadd family’s home was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, it put runaway slaves at ever greater peril. And for the first time, freeborn African-Americans like the Shadd family were also at risk of being captured and enslaved. Mary Ann and her brother moved to Canada, and the rest of the family soon followed.

In Chatham, Ontario, Mary Ann started a newspaper called The Provincial Freeman. This made her the first Black woman publisher in all of North America, and the first woman publisher of any race in Canada. The Freeman promoted abolition and women’s rights, yet also fed the soul of Ontario’s Black population (some 20,000) with literature and culture.

As the newspaper’s publisher and editor from 1853 to 1861, Mary Ann fearlessly traveled back and forth to the U.S. to gather news. After the Civil War broke out, she left her family behind in Canada, moved back to the U.S., and worked for the Union Army to recruit Black soldiers.

First a teacher, then a journalist, Mary Ann was never content to rest on her laurels. She liked to say “It’s better to wear out than to rust out.” She earned a law degree, making her the second African-American woman to do so, and spent the last decade of her life practicing law in Washington, D.C. Learn more about the remarkable Mary Ann Shadd Cary on this site.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862 – 1931)

Ida B. Wells (also known as Ida B. Wells Barnett, 1862 – 1931) remains one of the legendary names of American journalism. More than seventy years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a bus, Ida Bell Wells refused to move to the smoking car of a train where Black passengers were expected to sit.

Ida filed a lawsuit against the railroad company following this 1884 incident and won — though the decision was later reversed. The story of her courage spread, and she was invited to write for Black newspapers that were cropping up in big cities.

She contributed so many articles to The New York Age, The Detroit Plaindealer, and the Indianapolis World that she was dubbed “Princess of the Black Press.”

But Ida didn’t care to be a princess. In 1889 she started her newspaper in Memphis, her home town. Free Speech and Headlight supported women’s voting rights and promoted African-American education. Making so much noise about these issues made white people uncomfortable, and she was forced out of Memphis. Her newspaper had to be abandoned.

Ida moved to New York City and devoted her career to fighting lynching, the barbaric mob murders that claimed thousands of Black lives. Greatly respected during her lifetime, Ida’s reputation continued to grow after her death.

Journalism awards and scholarships have been established in her honor, and there’s a museum celebrating her life and work in her home state of Missouri. A monument to her legacy is currently being built in Chicago.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Jovita Idár (1885 – 1946)

Jovita Idár (1885 – 1946) was a Mexican-American journalist and activist who grew up a large family dedicated to improving the lives of the Latino community in Laredo, Texas and beyond. Clever and imaginative as a girl, Jovita loved to study and adored writing — especially poetry.

She earned a teaching certificate in 1903 and went to work in nearby Los Ojuelos. Her Mexican-American students were forced into poorly equipped, segregated classrooms. There weren’t enough chairs and desks for them; even basics like paper and pencils were in short supply. Jovita found it extremely frustrating and wondered if she could help the schools more as a journalist.

Jovita’s father published a newspaper called La Crónica, a strong voice for Mexican-Americans in Texas. Jovita joined the paper and went undercover to expose the horrendous living and working conditions of Mexican-American laborers. She discovered the power of the printed word to create social change.

Her greatest passion was improving education for girls and poor children. To promote feminist ideals, she started another newspaper, Evolución. She also wrote editorials for other papers that promoted social change.

When the Texas Rangers and U.S. Army came to shut down one of them, she stood in the doorway to keep them from entering. Jovita ran her father’s newspaper after he died in 1914, and dedicated her career as a journalist and activist to improving the lives, schools, and working conditions of Mexican-Americans.

You may also enjoy …

10 pioneering African-American Women Journalists

6 Female Journalists of the World War II Era

The Stunt Girls — 3 Fearless Pioneers of Investigative Journalism

Leave a Reply