Victoria Woodhull: Rabble Rousing Suffragist and First American Woman to Run for President

By Nava Atlas | On March 1, 2020 | Updated September 2, 2022 | Comments (0)

Shirley Chisholm may have been the first woman to seek the presidential nomination from one of the two major political parties — that was in 1972 — but exactly one hundred years before that, Victoria Woodhull (1838 – 1927) was the first woman to launch a national presidential campaign. She did so under the banner of the Equal Rights Party.

And running for president long before women even had the right to vote was just one chapter in an incredibly colorful, yet largely forgotten American life.

Victoria was a suffragist, publisher, stockbroker, orator, and agitator. She was also accused at various points of being a bigamist, prostitute, spiritual charlatan, and adulteress.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

A controversial figure in a tumultuous time

Imagine this scenario to see why the life of a rabble-rouser like Victoria Woodhull is still relevant today:

- A woman is running for president.

- The institution of marriage is being redefined, as are sexual standards.

- A culture war is raging between organized religion and secular beliefs.

- The rights and economic fortunes of women and immigrants are in flux.

- Popular spiritual and political leaders are caught in webs of hypocrisy.

- A nationwide financial collapse is followed by a resurgence of wealth that benefits the already super-wealthy in a competitive, aggressive era.

No, this isn’t a capsule of 21st-century America. It’s post-Civil War New York City — the late 1860s and early 1870s, to be exact. The issues and struggles are eerily similar, but the players are different — and far more dramatic and flamboyant than those in the public arena today.

Though nearly always mired in controversy, Victoria fought for what she believed in — equal rights for women, labor reform, and “free love” — the 19th-century term for granting women the opportunity to marry, have children, divorce, and take lovers without the interference of government and society.

In one of her many public speeches, she famously declared:

“Yes, I am a free lover! I have an inalienable, constitutional, and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can, to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere.”

With a large, squalid family never far from her side, Victoria and her equally colorful sister, Tennessee (Tennie) Claflin, shocked and challenged a post-Civil War society that was grappling with new ideas about class, religion, sexuality, and the role of women.

“The most famous woman in America”

Victoria and Tennessee, the sibling with whom she was closest, lived the classic rags-to-riches tale twice over, and crossed paths (often with dramatic consequences) with some of the most renowned and influential people of their time:

Cornelius Vanderbilt, Henry Ward Beecher and his sisters (Harriet Beecher Stowe and Isabella Beecher Hooker, and suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were among those who were friends and enemies of Victoria.

Though not as well remembered as some of her famous contemporaries today, Victoria was for a time called “the most famous woman in America.” She was always a divisive figure who inspired admiration and respect by some; loathing and fear by others.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Clairvoyant sisters and a family of charlatans

From the time they were young, the sisters were the star attractions of the Claflin family’s traveling medicine and clairvoyance show, taking full advantage of the public hunger for magnetic healing, magical elixirs, and spirit channeling in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Victoria possessed a distinctive aquiline beauty and carried herself with a regal air. Tennessee’s wily intelligence was masked by a bubbly, coquettish demeanor and an uninhibited spirit.

Spiritualism was a powerful cultural force in the post-Civil War years, a time when those who lost loved once in the devastating conflict looked for ways to communicate with the dead. Victoria and Tennessee became skilled at convincing those who were grieving that they could do just that.

The sisters’ earnings became the main support of their unscrupulous parents, a pair of uneducated, conniving rubes, and their large brood of siblings.

Chased from one town to another, the eccentric Buck and Roxanna Claflin were purveyors of quackery and fraud, and the attractive daughters raised suspicions of selling sex along with their magical cures and messages from the dead.

A forced teenage marriage to a dissipated alcoholic

The truly dramatic portion of Victoria’s life began when she was in her late twenties. She and the family had temporarily settled in St. Louis after wandering from one Midwestern city to another dispensing their snake oil and doing spiritual readings.

The family, minus a few siblings who had grown and broken away, now included Canning Woodhull, a dissipated alcoholic and failed doctor. Victoria’s parents had married her off to Woodhull when she was barely fifteen.

Though she was repulsed by him from the start, the couple managed to have two children — Byron, a boy of limited mental capacity, and Zula Maud, a daughter who was Victoria’s joy.

A life-changing second husband

At a meeting of the St. Louis Spiritualists Society, where she made an impromptu speech, Victoria caught the eye of Colonel James Blood.

A Civil War veteran and ostensibly an upstanding citizen, Blood harbored radical views on social issues for the time, including those on sexuality and women’s rights. He helped give voice and order to Victoria and Tennie’s vague notions and helped shape their predilection for controversial causes.

After divorcing Woodhull and taking Blood for her husband, Victoria led her family to New York City in 1868, following a directive from Demosthenes, her longtime spirit guide. Demosthenes even conveyed to Victoria the exact address of the building on Great Jones Street where the family was to take residency, or so she claimed.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Becoming the “lady stockbrokers”

Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, the railroad magnate (and one of the 19th century’s “robber barons”) was at the time in his twilight years and considered the richest man in America.

He scorned clergymen and physicians, instead taking comfort from spiritual mediums and healers of all sorts. The sisters wasted no time in making their way into his life once they became aware of his predilections.

Victoria brought Vanderbilt messages from his favorite son, who had died in the Civil War, and Tennie eased his pains with her healing hands. Soon she attended to Vanderbilt’s other physical needs by becoming his mistress. Vanderbilt may have chosen Tennie for his bedmate, but he admired Victoria’s intelligence.

Victoria took heed of Vanderbilt’s stock market tips and made a tidy sum in the aftermath of the 1869 Black Friday collapse of the gold market. Acquiring a taste for finance, Victoria and Tennie prevailed upon Vanderbilt to back them as they opened their own Wall Street brokerage firm.

Causing a sensation as “the lady brokers,” the sisters were the first American women to enter into the profession.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly; a presidential run

With the behind-the-scenes assistance of Blood as well as the radical intellectual Stephen Pearl Andrews, the sisters’ newfound wealth gave them the means to launch Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly.

It was a lively newsprint journal that served as a platform for their views on social issues, women’s rights (including ownership of their own bodies), marriage and divorce, and sexual freedom. It was particularly concerned with exposing political and moral hypocrisy.

The first issue also announced Victoria’s candidacy for president of the United States, another first for American women. This was radical indeed, given that women would not be granted the right to vote until some fifty years later. And never mind that she was also a bit under the constitutional age to become president.

Victoria named as her running mate Frederick Douglass. The famed African-American abolitionist and orator never agreed to the nomination, and never campaigned with her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A minister’s seductions — the Henry Ward Beecher scandal

Victoria’s nascent friendship with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women’s movement leaders made her privy to a secret: Henry Ward Beecher, the beloved and nationally famed minister of Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church, had seduced Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of his best friend, Theodore Tilton.

Spreading among Victoria’s influential circle of contemporaries were whispers that the affair was but one in a long series of seductions by Beecher of married women in his parish.

Far from being shocked, Victoria viewed Beecher as a man who secretly practiced the sexual freedom that she openly preached. For some time, she explored a way to expose his hypocrisy that would be to her benefit.

In the midst of an intensive and lengthy cover-up, Theodore Tilton became the surprising emissary sent to placate Victoria. Elizabeth’s moody and obsessive wronged husband instead fell victim to Victoria’s charms, resulting in a brief, passionate affair.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Victoria speaking before the House Judiciary Committee along with a group of suffragists on January 11, 1871

. . . . . . . . . . .

Ascending in the women’s rights movement

Upon presenting an argument before the House Judiciary Committee in the nation’s capital for women’s right to vote under the protection of the 14th amendment, Victoria was embraced as a leader for the cause by the National Women Suffrage Association.

Yet Victoria’s alliance with the suffrage movement was always uneasy. She was too untethered and eccentric for the ladies, who were, for the most part, prim and proper. And, as history would later show, rather racist.

Though increasingly spurned by the members of the women’s rights movement, Victoria’s most loyal friends invited her to participate in the winter National Woman Suffrage Association convention.

There, she rallied the women to form their own political party, at the top of which was her own bid for the presidency of the United States. This would be, she proclaimed, a way to gain attention for the cause of suffrage.

At the May 1871 speech to the Woman’s Suffrage Convention, Victoria gave what would become one of her most famous speeches, “A Lecture on Constitutional Equality,” now known as “The Great Secession Speech.” In part, she said:

“If Congress refuses to listen to and grant what women ask, there is but one course left then to pursue. Women have no government. Men have organized a government, and they maintain it to the utter exclusion of women….

Under such glaring inconsistencies, such unwarrantable tyranny, such unscrupulous despotism, what is there left for women to do but to become the mothers of the future government?

There is one alternative left, and we have resolved on that. This convention is for the purpose of this declaration. As surely as one year passes from this day, and this right is not fully, frankly and unequivocally considered, we shall proceed to call another convention expressly to frame a new constitution and to erect a new government, complete in all its parts and to take measures to maintain it as effectually as men do theirs.

We mean treason; we mean secession, and on a thousand times grander scale than was that of the south. We are plotting revolution; we will overslough this bogus republic and plant a government of righteousness in its stead, which shall not only profess to derive its power from consent of the governed, but shall do so in reality.”

No one could deny Victoria’s power to stir up a crowd like very few others, male or female, could. Her speeches, with their drama and hints of scandal, were extremely popular and often drew thousands.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Depicting Victoria, “Get thee behind me, (Mrs.) Satan!” was a well-known 1872 cartoon by Thomas Nast

. . . . . . . . . . .

Exposing the Beecher-Tilton affair

As Victoria became more of a public figure, she was reviled for her views, especially when it came to free love. This was the Victorian era, during which the ideal of womanhood was to be “the angel in the house.” In the public eye, Victoria was Mrs. Satan — the polar opposite of an angel.

Pushed to her limits by a double standard that was destroying her reputation, Victoria seethed as she observed her critics thriving. The public taunts by none other than Beecher’s sisters, Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe proved to be the last straw.

Victoria exposed the Beecher-Tilton affair, first in a speech, then in the Weekly, declaring that she refused to be made a martyr for her views.

Theodore Tilton, independent of Victoria’s actions, had pressed charges against Beecher for “criminal seduction,” culminating in what was to become the most sensational trial of the nineteenth century, one that was a national obsession for months.

In prison on election day

Anthony Comstock, a self-righteous battler against all that he deemed immoral, took a copy of the scandal issue of The Weekly to the Federal authorities. He had proof that it had been sent through the mails, and sending obscenity through the mails was a Federal offense.

Victoria and Tennie had just left the office of the Weekly with a fresh bundle of papers and were riding home in a carriage when U.S. Marshalls stopped them with a warrant for their arrest. The sisters were taken to Circuit Court and questioned.

On Election Day, presidential candidate Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee were held the Ludlow Street jail.

The plight of Victoria and Tennie on such obviously trumped-up charges brought them a new wave of sympathizers and supporters. Their jail cell was crowded with visitors and there was no lack of gentlemen willing to pay their court costs and attorneys fees.

Days later, Victoria and Tennie appeared before a Grand Jury in a packed courthouse. The newspapers howled at the blatant invasion of freedom of the press.

The brief boost to the Weekly’s circulation was a temporary salve for its declining fortunes, but her ordeals left Victoria exhausted and dispirited. Abandoned by even her staunchest allies and friends, Victoria’s frustration and anguish drove her to divorce Blood.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Losing Cornelius Vanderbilt’s support

Victoria’s reputation as an orator, businesswoman, muckraking journalist, and advocate for women’s suffrage grew, even as the advice and moral and financial support of Cornelius Vanderbilt was waning.

His new, younger wife, plucked from the cream of society, was a more appropriate choice for him than Tennie Claflin, in the estimation of the elderly Commodore’s grown sons and daughters.

Vanderbilt’s new bride lured him back to traditional religion and proper medical doctors. Vanderbilt’s abrupt withdrawal from their lives was compounded by the depressed economy following another market crash.

A downward spiral for the Woodhull and Claflin clan

The national mood seemed to be swinging back to more conservative views. The radical stances espoused by Victoria and Tennessee experienced profound pushback, and they themselves felt increasingly ostracized and marginalized.

The Woodhull and Claflin clan were forced to give up their 38th St. mansion. They fought to keep the Weekly alive at all costs, but it soon grew impossible to do so.

Victoria embarked on a grueling lecture tour to support the publication and the family. By this time, she had taken in her first husband, Canning Woodhull, now addicted to morphine as well as alcohol. Outraged society charged Victoria with “living with two husbands.”

The sisters’ fortunes were quicly waned and their brokerage slipped into debt. Victoria was suffering from nervous exhaustion, and the future was bleak.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A disputed will saves the day

When all hope seemed lost and the Woodhull and Claflin clan was clearly in crisis mode, the Vanderbilt fortune returned in the form of a disputed will. The old Commodore, having just died, left nearly his entire fortune to his son William in hopes of keeping his railroad empire intact.

His remaining children, outraged by their token bequests, went to court to contest the will, charging that their father had been of unsound mind when he had last updated it. Portraying him as a nutcase unduly influenced by bogus healers and spirit mediums, they devised a plan to call Victoria and Tennessee as witnesses.

This threat propelled William to quick action. Noting the financial distress of the Claflin family, he offered to pay the sisters off with a tidy sum if they’d leave the country before they could be called to the witness stand.

Victoria and Tennessee haggled with William, getting him to agree to an amount that was a small fortune for any ordinary American family not in the league of the Vanderbilts.

Finding refuge in England

Victoria and her children, Tennie, and Buck and Roxana Claflin were suddenly comfortable again thanks to the Vanderbilt payoff, and boarded a ship bound for England.

When Victoria set sail with her two children, with Tennessee and their parents still in tow, she vowed to return as soon as she could to resume her fight for her beliefs, and to vindicate herself against those who had tried to destroy her.

After having been mired in controversy for nearly all their lives, the sisters now craved respectability. Victoria captured the fancy of a wealthy young banker, John Biddulph Martin, while lecturing to a curious British audience. Eventually, over the objections of his family, the two were married.

Tennessee married an even more fabulously wealthy baronet. The sisters fought as hard to gain social standing as they had previously done to earn notoriety.

Unable to completely rest on their laurels, the sisters continued to promote for favored causes, though in a much quieter manner.

The sisters remained in England for the rest of their lives, enjoying a relatively peaceful existence and doing good works, careful to steer clear of controversy — at least, most of the time.

Victoria Woodhull died on June 9, 1927 at Norton Park in Bredon’s Norton, Worcestershire, England.

Victoria Woodhull’s complicated legacy

Though many of Victoria’s views on social issues and women’s rights were quite progressive, her stances on other issues were surprisingly regressive.

Despite her belief that women should have domain over their own bodies, she was virulently anti-abortion. She also ascribed to eugenics and supported forced sterilization of those she deemed unfit to breed.

Though she had chosen Frederick Douglass, an African-American, as her unwitting running mate, there’s also evidence that she, like a number of other white suffragists of her time, was racist.

Victoria was recognized as a powerful extemporaneous speaker, though scholars almost uniformly believe that her writings and more polished speeches were heavily edited by her second husband, James Blood, and fellow radical Stephen Pearl Andrews. This no doubt is due to her lack of formal education.

Yet despite her muddled legacy and lifetime of being embroiled in controversy and scandal, Victoria Woodhull is recognized as a fearless advocate for women’s freedom and for the bold statement of running for president at a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote.

Here are just a few ways that Victoria has been recognized over the years:

A historical marker was erected outside the Homer Public Library in Licking County, Ohio (where the Claflin clan resided for some years. It honors Victoria as the “First Woman Candidate For President of the United States.”

- 1980: The Broadway musical Onward Victoria was inspired by her life. It wasn’t very well received, but still …

- 2001: Victoria Woodhull was belatedly inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

- 2003: The Woodhull Freedom Foundation is an advocacy organization for sexual freedom in a human rights context.

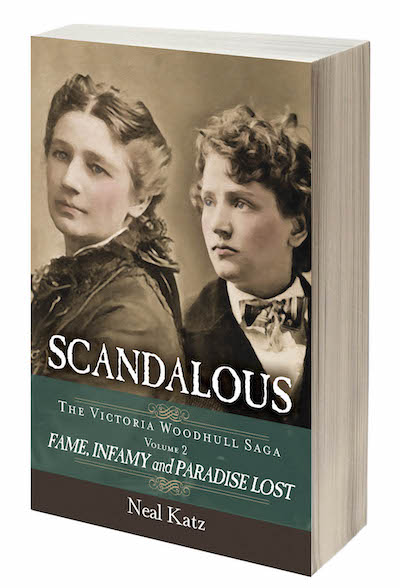

- There have been numerous full-scale biographies of Victoria in recent years, including Other Powers by Barbara Goldsmith, Notorious Victoria by Mary Gabriel, The Scarlett Sisters by Myra Macpherson, and others.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Victoria Woodhull

- Wikipedia

- The Strange Tale of the First American Woman to Run for President (Politico)

- 9 Things You Should Know About Victoria Woodhull

- Biography of Victoria Woodhull by Theodore Tilton (1871)

- Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull

Leave a Reply