Ida B. Wells, Fearless Journalist and Crusader for Justice

By Nava Atlas | On May 9, 2020 | Updated February 9, 2024 | Comments (0)

Ida B. Wells (1862 – 1931), also known as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, was a fearless journalist and crusader in the early civil rights movement. She was a feminist, editor, sociologist, and one of the founders of the NAACP.

She was best known for spearheading a national antilynching campaign, through which she worked tirelessly to end the uniquely American practice of the public mob murders of African-Americans. Wells’s reputation continues to grow, even decades after her death.

Journalism awards have been established in her name, scholarships are endowed in her honor, and there’s a museum celebrating her legacy in her hometown in Mississippi.

In 2020, nearly 90 years after her death, Ida B. Wells was awarded a long overdue posthumous Pulitzer Prize in the category of Special Citations and awards for “her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.”

Early life

The following biography of Ida B. Wells is excerpted from Afro-American Women Writers 1746 – 1933 by Ann Allen Shockley:

For more than forty years Ida B. Wells was one of the most fearless and one of the most respected women in the United States.” She was widely known as a crusading editor, journalist, organizer, lecturer, social reformer, and feminist.

Born a slave on the threshold of freedom, 16 July 1862, at Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ida Bell Wells was the oldest of eight children. Her parents were Jim Wells, son of his master and a highly skilled carpenter, and Elizabeth Warrenton, an expert cook. The two were married in slavery and repeated their vows when freed.

Deeply religious, Ida’s parents instilled in her biblical teachings and the importance of getting an education. She went to Rust College in her hometown, a Freedmen’s Aid school with all grade levels. A “pretty little girl, slightly nut-brown, with delicate features” she became an exceptional student in the school where her father was a member of the first Trustee Board.

When the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 reached Holly Springs, Ida’s parents and their youngest child died. Two other children had passed on earlier, leaving Ida and her four brothers and sisters.

Showing at the age of fourteen the strength and determination that marked her all her life, she undertook to keep the family together.

After passing the examination for county schoolteacher, she was assigned a one-room school six miles away. After one term, she was encouraged by a widowed aunt to come to Memphis to teach and live with her. While studying for the city school examination, she taught in Shelby County.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Refusal to move from a white train car and litigation

In May 1884, when she was traveling on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad to teach in Woodstock, Tennessee, a conductor asked her to move to the smoking car. When she refused, the conductor, with the assistance of the baggage man, tried to force her out. During the fracas, lda braced her feet on the back of the seat and bit the conductor’s hand.

Getting off at the next stop, she returned to Memphis and brought a suit against the railroad. She won the case and was awarded five hundred dollars and damages.

In writing of her victory, the white Memphis Daily Appeal of December 25, 1884, captioned the story: “A Darky Damsel Obtains a Verdict for Damages against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad.”

Her triumph was short-lived, however, for the railroad appealed and the Supreme Court of Tennessee reversed the decision on April 5, 1887. It was the first case in which a colored plaintiff in the South had appealed to a state court since the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill by the United States Supreme Court.

First forays into journalism

Ida qualified to teach in the Memphis school system, and became a primary grade teacher for seven years. To further her education, she attended summer school at Fisk University, studied privately with experienced teachers, and read voraciously.

Her writing talent emerged when she was elected editor of a small church paper, the Evening Star. Then, much to her surprise, for she had no newspaper training, she was invited to contribute to the Living Way, a Baptist weekly. Adopting the pen name of “Iola,” she wrote her first article for the paper on the railroad suit.

Soon the young journalist, who had learned to “handle a goose-quill, with diamond point, as easily as any man in the newspaper work,” was in demand. She wrote for the American Baptist, Detroit Plaindealer, Christian Index, Indianapolis World, Gate City Press, and A. M. E. Review.

She also edited the “Home” department of Our Women and Children. Called the “brilliant Iola” and “Princess of the Press,” she was the first woman to attend the Afro-American Press Convention in Louisville, Kentucky, and was elected assistant secretary. There she read a paper, “Women in Journalism, or, How I would Edit.”

Buying into newspaper ownership

Her opportunity to edit a paper came when she bought a one-third interest in the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight in 1889.

Not one to hold her tongue or her pen, she wrote an article about the poor conditions of the local Black schools, deploring not only the physical structures but the inadequacies of the teachers also. The exposé provoked ill feeling against her among both Blacks and whites, and she was not rehired to teach the following year.

She had never particularly enjoyed teaching because of its “confinement and monotony,” and now she set out to express what she called her “real me” in newspaper work.

Shortening the name of the paper to the Free Speech, she devoted full-time to traveling for the paper and making it a success.

Free Speech soon became a household word “up and down the Delta.” It was printed on pink paper so the illiterate could identify it, and circulation increased from fifteen hundred to four thousand.

Urging Black people to move west to escape lynching

On March 9, 1892, the lynching in Memphis of three young Black businessmen, owners of the People’s Grocery Company and friends of Ida’s, changed the direction of her life.

Away at the time in Natchez, Mississippi, she returned to write blistering editorials that condemned whites for permitting the lynching and urged its Black citizens to leave the city and go west.

Hundreds of Black people began to move away, including entire church congregations. She also encouraged Blacks to boycott white businesses, introducing the first Black boycott.

A serious death threat

In May, Ida B. Wells left an editorial at the paper to be published while she attended the A. M. E. General Conference in Philadelphia, where she was to be the guest of author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. From there, she was scheduled to go to New York to see T. Thomas Fortune, the brilliant editor of the New York Age.

While in the company of Fortune, she learned about the destruction of her press by an angry white mob. Her partner, J. C. Fleming, had been run out of town, and friends sent word warning her not to return, for whites were threatening to kill her on sight.

The editorial that ignited the wrath of whites concerned the lynching of Black men because of white women:

“Nobody in this section believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men assault white women. If southern white men are not careful they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Militant anti-lynching writings

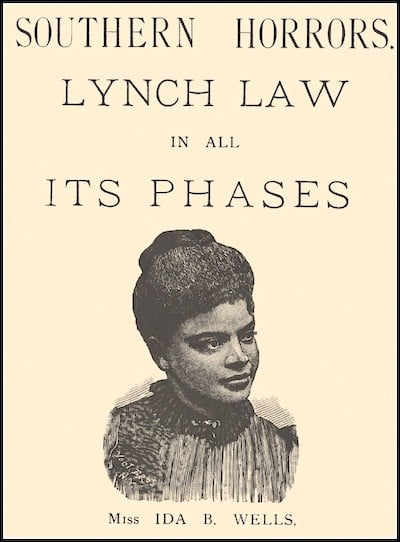

Now an exile from home, Ida was asked by T. Thomas Fortune to write for the New York Age. For the June 5, 1892 issue, she substantiated her Memphis editorial by writing an incisive factual front-page piece on lynching. Four months later, it was published again in pamphlet form and called Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892).

Her writing aroused the interest of the eminent race leader, Frederick Douglass, who published a letter in the pamphlet citing her as a “Brave woman!” That was the beginning of a lifetime friendship between the two.

Ida B. Well’s militant writings against lynching awakened other Black women to rally behind her cause. Victoria Earle Matthews, writer and reformer of New York, and Maritcha Lyons, a Brooklyn schoolteacher, led a group of Black women to give lda a testimonial at Lyric Hall, in October, 1892. She was presented with five hundred dollars and a gold brooch in the shape of a pen.

This event turned out to be an important occasion in her life, for before a large gathering of prominent Black women, she gave her first public lecture on the horrors of lynching. The testimonial had another historic aspect also, for it laid the groundwork for the beginning of the Black women’s club movement.

A writer and speaker in demand

Out of it came the Women’s Loyal Union. Ida B. Well’s ability as an organizer was readily recognized, and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin of Boston asked her to assist in forming the Woman’s Era Club. Earning the title “Mother of Clubs,” she helped form women’s groups throughout New England and in Chicago, where one was named in her honor.

She was an outstanding worker in the National Association of Colored Women and, in 1924, ran for president against Mary McLeod Bethune.

Ida now was receiving numerous requests to speak on the subject of lynching. During April and May of 1893, she traveled to England, Scotland, and Wales, and in 1894 visited England again for six months. Her speeches there led to the formation of an Anti-Lynching Committee.

Besieged to write as well as to speak, she was asked to send back articles about her trip to the Chicago daily paper, the Inter-Ocean (subsequently the Herald-Examiner), writing a column “Ida B. Wells Abroad.” She commented in her autobiography that she was the first Black person to become a regular paid correspondent for a daily paper in the United States.

Always quick to publicize racial disparities, she protested against the barring of Blacks from the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. She, along with Frederick Douglass and Frederick J. Loudin, an original Fisk University Jubilee Singer, appealed for funds to publish a pamphlet protesting the discrimination.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Settling in Chicago; becoming a wife and mother

Ida B. Wells settled in Chicago, where she wrote her indictment, A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States, 1892-1893-1894 (1895). This notable work presented both lynching statistics and its history.

She joined the staff of the first Black Chicago newspaper, the Conservator, which was owned by Ferdinand L. Barnett, a widower and attorney. Romance entered the picture, and on June 27, 1895, Ida married Barnett. They had four children, but motherhood did not stop her from continuing her writing and lecturing.

In the role of social reformer, she founded the Negro Fellowship League in the most blighted section of Chicago’s South Side. The league gave a refuge to those who were homeless, offered religious services, and helped the unemployed. As the first Black woman to be appointed a probation officer, she used the league’s services to assist with her work.

An aggressive feminist, she organized in January 1913 the first suffrage group composed of Black women, the Alpha Suffrage Club, which published a newsletter, the Alpha Suffrage Record.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

A focus on antilynching activism

She was called upon also to investigate riots in such places as Springfield, Illinois; Elaine, Arkansas; and East St. Louis. Her stories on these events ran in the Chicago Defender, Broad Ax, and Whip. She carried her mission against mob rule all the way to the White House in 1898.

Armed with resolutions from a Chicago rally against lynching, she presented them to President William McKinley. In 1900, she published a pamphlet, Mob Rule in New Orleans: Robert Charles and His Fight to the Death.

A firm believer in organizing for unity, she was one of the original group who, with W. E. B. Du Bois, conceived of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

. . . . . . . . .

10 Pioneering African-American Women Journalists

. . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Ida B. Wells Barnett

All through her life, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a dynamic, bold, and strong-minded woman who fought against lynching and for the rights of her people.

She spoke her mind whenever the occasion warranted, and because of this, she was frequently “not only opposed by whites, but some of her own people were often hostile, impugning her motives.”

She fought a “lonely and almost single-handed fight” against lynching long before men or women of any race entered the arena.”

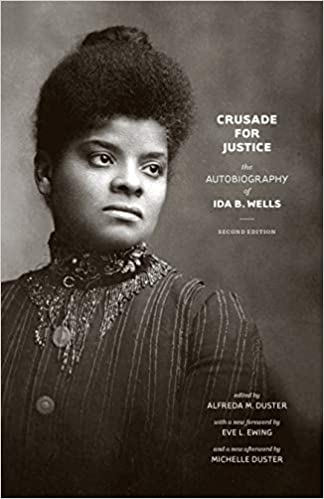

She left her story in an autobiography begun in 1928. Her memoirs were eventually edited by her daughter, Alfreda M. Duster, and published under the title Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of lda B. Wells (1970).

On March 25, 1931, Ida B. Wells died of uremic poisoning. In 1940, the Chicago Housing Authority named a housing project on the South Side in her honor. Ten years after that, the city designated her as one of the twenty-five outstanding women in Chicago’s history.

. . . . . . . . . . .

More about Ida B. Wells

On this site

Books by Ida B. Wells-Barnett

- Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases (1892)

- A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings

in the United States, 1892-1893-1894 (1895) - Lynch Law in Georgia (1899)

- Mob Rule in New Orleans: Robert Charles and His Fight to the Death (1900)

- Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells,

edited by Alfreda M. Duster (second edition, 2020)

Biography

- To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells by Linda McMurry (1999)

- Ida: A Sword Among Lions by Paula Giddings (2009)

- Passionate for Justice: Ida B. Wells as Prophet for Our Time by Catherine Meeks (2019)

More information

Leave a Reply