The Literary Friendship of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings & Zora Neale Hurston

By Ann McCutchan | On June 4, 2021 | Updated June 13, 2023 | Comments (8)

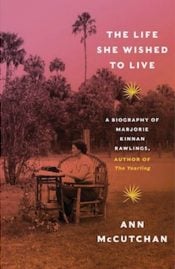

The following musing on the friendship of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Zora Neale Hurston, two complex literary personalities, is excerpted and adapted from The Life She Wished to Live: A Biography of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Author of “The Yearling,” © 2021 by Ann McCutchan.

This biography revives interest in a mid-20th century writer whose work successfully bridged literary and commercial qualities.

A Pulitzer Prize winner and household name in her time, Rawlings deserves to be remembered and read. Further thoughts on The Life She Wished to Live will be found following this excerpt. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved:

In the summer of 1942, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was invited to speak at historically Black Florida Memorial College in St. Augustine. One of the instructors that term was Zora Neale Hurston. At the time, Zora was completing her memoir, Dust Tracks on a Road, covering her childhood in Eatonville, Florida’s first all-black incorporated city.

A budding friendship in a complicated era

Marjorie had just published Cross Creek, her memoir of the north-central Florida hamlet she had, fourteen years earlier, adopted as home. The two women became acquainted, and when Marjorie returned to Castle Warden, the St. Augustine hotel her husband, Norton Baskin, owned and operated, she told him she’d “met the most wonderful woman.”

In fact, she had immediately invited Zora to tea at their hotel apartment. But as soon she told Norton about it, she regretted the offer. She suggested she meet Zora elsewhere, not at the hotel, where white regulars might frown on a fashionably dressed black woman passing through the lobby and withdraw their business.

Marjorie’s concerns were real. Florida was an entrenched pocket of the Deep South; Jim Crow laws ruled. Lynchings still occurred, especially in the area between the Georgia-Florida line and north-central Florida, once home to plantations. There had been five plantations in Alachua County, 70 miles west of St. Augustine, where Cross Creek was tucked away.

Marjorie was herself ambivalent about black-white relations. Growing up in Washington, D.C., she had absorbed conventional racist attitudes and in 1928, when she bought a run-down Florida orange grove and moved there to write, she had hired several black workers to tend the grove and run her household.

Some were lodged in a tenant shack behind her farmhouse. The maid who served Marjorie breakfast in bed wore a uniform and headpiece. “Mrs. Rawlings, kind as she was, never asked her workers to do anything,” Idella Parker, her longest-serving housekeeper, remembered. “She told them.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

. . . . . . . . . .

Yet Marjorie paid higher wages than the going rate, covered her workers’ medical bills, and was considered liberal by her white Cracker neighbors. By the time she met Zora, she had won a Pulitzer Prize for The Yearling and begun moving in elite, highly educated white circles. She had been Eleanor Roosevelt’s guest at the White House. She was awakening to the twin causes of civil and human rights.

Norton, an Alabama native, assured Marjorie Zora was welcome and instructed a black assistant to watch for Zora at the appointed hour and “get her through this lobby the fastest you ever seen and get on the elevator, and get her up there.”

The hour came, but neither Norton nor his assistant saw anything of Zora. Marjorie’s guest had foreseen the situation, entered the hotel through the kitchen, and found her way to the Baskin apartment.

When Norton checked with his wife on the hotel phone, she told him what Zora had done. “We’re having tea and having more fun than you’ve ever heard of,” she told him. “And if you’ve got any sense, you’ll come on up here.”

To a friend, Marjorie described Zora as “a lush, fine-looking café au lait woman with the most ingratiating personality, a brilliant mind, and the fundamental wisdom that shames most whites.

She puts the full responsibility for Negro advancement on the Negroes themselves and has no use for the left-wingers who consider her a traitor, nor for the ‘advanced’ Negroes who belong to what she calls the fur-coat peerage.

“She says that both ‘advanced’ whites and ‘advanced’ negroes make a mistake in handling the Negro problem with kid gloves, each afraid of the other.”

What Zora told her squared with Carla Kaplan’s assertion that Zora “staked out a conservative position on race that grew from her fierce pride in black institutions and her suspicion of any mask unless it were her own.”

Zora, from birth negotiating race, sex, and class to achieve artistry and serve ambition, wore many masks, and as friendly as she and Marjorie became, she modulated her behavior at first, observing the Southern code of manners, in which blacks adopted what Hilton Als has described as “theatrical modesty and duplicity” to manage their inferior position.

Marjorie might have found ease in the idea that the oppressed are responsible for their condition. Yet the meeting challenged her tendency toward what James Baldwin would call “the lie of pretended humanism.”

Marjorie’s ambivalence was apparent in “Black Shadows,” a chapter in Cross Creek, in which she highlighted several “reasonably accurate” clichés about Negroes: they were childlike, carefree, religious “in an amusing way,” liars, undependable.

At the same time, she called these clichés superficial, pointing to the Negro population’s African heritage, the unspeakably difficult adjustments to slavery and, since Reconstruction, to “so-called civilization.” The Negro is “left to shift for himself for the most part instead of being cared for,” she wrote.

. . . . . . . . .

The Life She Wished to Live is available wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

A shifting understanding of race

After meeting Zora, Marjorie’s understanding of race relations began to shift significantly, though not without the interior conflicts, the steps forward, back, and sideways, that monumental change entails. That she had been urged to break custom by her Alabama-born husband led to the couple’s discussions about racial prejudice and Negro rights for many months to come.

Marjorie and Norton were not alone in this; their changing views corresponded with a pro-civil rights movement among educated whites as a whole, sparked by World War II. Nazism had forced some white Americans to own up to their racist policies and behaviors, while across the sea in the armed forces, men and women of many ethnicities served shoulder-to-shoulder, softening racial divisions.

As the United States emerged to lead the “free world,” it would have to embrace civil rights reform as bedrock — both as proper ideal, and as defense, for as the Cold War began, Soviet propagandists keen on locating the “free world’s” weaknesses, found an easy target in racism, particularly in the South.

. . . . . . . . .

Zora Neale Hurston

. . . . . . . . .

Zora reacts to Cross Creek

Early in 1943, Zora read Cross Creek and sent Marjorie an enthusiastic response. “Twenty-one guns!” she wrote. “It is a most remarkable piece of work. You turned your inside light on that community life, and it broke like day.

“Whether it pleases you or not, you are my sister. You look at plants and animals and people in the way I do. You are conscious of the three layers of life, instead of the obvious thing before your nose. You see and feel the immense past, what is now, and feel inside you something of what is to come. Therefore, you are not pacing the cell of the current hour. You are free, because you have made your peace with the universe, and its laws. You are deep and fine.”

“You did a thing I like in dealing with your Negro characters,” Zora continued, referencing “Black Shadows.”

“You looked at them and saw them as they are, instead of slobbering all over them as all of the other authors do. They talk real too, and act as I know them. You have done a remarkably able thing with the Negro idiom. It is so accurate. I am so sick and tired of that blackface minstrel patter that is put out as Negro dialect. I am not objecting to the bad grammar but the lack of imagination.

You catch this thing as it is. You note the “picture talk” that’s something of a linguistic hieroglyphics. I am tickled to death with you, Sugar. I love your description of the women’s behinds. “Box” and “shingle” and they fit the thing so beautifully. You were thinking in hieroglyphics your ownself. You have written the best thing on Negroes of any white writer who has ever lived.”

By July, Norton Baskin was en route to India with the American Field Service. Soon afterward, Marjorie heard from Zora, whom she had written about trouble starting a new book, using it as an excuse to decline Zora’s invitation to take a river trip together.

The truth was, Marjorie was embroiled in a lawsuit brought against her by a white neighbor who’d been offended by Marjorie’s depiction of her in Cross Creek. Marjorie was reluctant to travel openly with a black friend, as it might prejudice a critical segment of the public — such as white Crackers sitting on a jury — against her.

Zora replied with an enthusiastic desire to help. “How I wish that I were not doing a book too at this time! I would be so glad to come and take everything off your hands until you are through with yours …”

Deeply moved, Marjorie wrote to Norton, not knowing when or where he would receive the letter.

“The Negro writer, Zora Neal Hurston, has done one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever known,” she said, referring to Zora’s impulse. ”When she and I have finished our present books, I shall take the trip with her if it costs me the lawsuit and your business, not, God knows, in any spirit of condescension but with a desire to learn and to know.”

A surprise visit

Shortly before Christmas, Marjorie wrote Zora to confirm her Daytona Beach mailing address; she would ship her a holiday box of fruit. Again, she expressed frustration with her writing, and Zora immediately drove the one hundred miles from Daytona to the Creek to give Marjorie a boost.

When Zora arrived, Marjorie was in Gainesville, Christmas shopping. Martha Mickens and her daughter Sissy, two of Marjorie’s black housekeepers, invited Zora to wait. Zora carried her bags to the women’s crowded tenant house.

For Norton, Marjorie described Zora’s surprise appearance:

“Well, I had the most mixed emotions. I was so touched by her doing it, as I was touched by her offer to do my housekeeping while I worked — and it was supper time, and it was nighttime and bedtime — and dat old debbil prejudice fair stuck a needle in me. I was ashamed, and I was worried, and I thought this would probably be the evening Mrs. Glisson [a white neighbor] would come up to ask me something, and the word would go out [that Marjorie had a Negro guest], and I would lose the lawsuit!”

But — “Damn it, now is the time for all good men to come to the aid of a moral principle!”

Zora’s bags were brought to the farmhouse guest room. The women would share the home as equals. “I was amazed to find that my own prejudices were so deep,” she admitted to her husband. “But I felt that if I ever was to prove my humanitarian and moral beliefs, even if it cost me the lawsuit, I must do it then.”

Grappling with prejudice

In spring 1944, Marjorie’s young friend Julia Scribner (the publisher’s daughter) visited Cross Creek; the two women asked Idella Parker to take them to a black church — an effort to step inside the black community, to understand it. The trio found “an old shack of a church” and Marjorie gave Idella three dollars for the pastor, with a request to hear some singing.

“It seemed awful to walk into someone’s church and buy their songs,” she wrote to Norton, though she wasn’t sorry to have played the cultural tourist — it was a start.

A day or two later, Marjorie took Julia to a cocktail party in Ocala, drank too much, and when a guest made a racist remark, Marjorie held forth on “moral principles” until everyone except Julia turned against her. A friend told Marjorie, “You have never been hated in your life as you are hated here tonight.”

About this incident, Norton responded:

“… you will gain nothing by trying to convince the hidebound Southerner. Their beliefs on the question are firmly congealed and they are determined to keep them intact … Trying to argue the question with them merely increases their hate of the movement and plants the idea that the problem is getting out of hand and something has to be done.”

And that something, Norton suggested, was more violence against the Negroes.

Now Marjorie was reading Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, a comprehensive analysis of the racial divide, which might have influenced, in April, her advice to Idella about income taxes. Idella wanted to pay hers, but Marjorie asserted no one would catch her if she didn’t.

A tax-paying citizen should have the right to vote, Marjorie said, along with all other privileges; she was well aware that the fifteenth amendment, passed nearly 75 years before, was routinely circumvented in the South, through white primaries, poll taxes, literacy tests, long residency requirements, and other obstacles.

She was upset that blacks were drafted in wartime: “You can’t force men into military service for their country, without giving them the same rights as anyone else,” she wrote Norton.

But it was one thing for Marjorie to take a stand on paper or at a party, another to continue wrestling with personal prejudice, revealed in her own language and behavior.

A few days later, Marjorie admitted to Norton her revulsion to black skin. “I still have to fight a lingering prejudice, and when little black Martha [Sissy’s daughter] touches me, as she loves to do, I cringe. But if one recognizes it for a prejudice and a hang-over from one’s prejudiced training, it will pass.”

Norton came home that fall. Marjorie began publicly addressing the racial divide. At historically black Florida A & M College in Tallahassee, she was the principal speaker for a two-day celebration honoring black educator/activist Mary McLeod Bethune.

Marjorie’s address, “A Floridian’s View of Mary McLeod Bethune” is lost to history, but, she wrote to a friend, “It was a fascinating experience and I am more than ever ashamed of the people who try to hold the Negroes back.”

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Yearling

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contradictions and controversies

Still, Marjorie’s position was fraught with contradictions. In the post-war era, The Yearling had been called out for offensive language, primarily a few uses of the “n” word. In January 1946, the book was withdrawn from required reading at the predominantly black Morris High School in the Bronx, after irate citizens deemed it a “poison” book for its portrayal of Negroes.

Members of the National Equal Rights League protested The Yearling’s spot on a summer reading list for James Monroe High School, also in the Bronx, with the same objections.

Upset, Marjorie wrote to the Rev. Frank Glenn White, director of the People’s Institute of Applied Religion, which espoused social activism and equal rights in particular, and to People’s Voice, addressing her use of the “n” word in The Yearling. The newspaper published part of her letter, introducing her as someone considered “a staunch supporter of Negroes.” She wrote:

“I approve with all my heart the policy of laying a taboo on the use of the word, not because any word is in itself offensive, since all words are only their connotations, but because those who use the word in ordinary speech or casually in print are those who have the wrong attitude, not only toward Negroes, but toward all of life and Christian living.

But in your zeal, you must not see things out of proportion. This is one cause of my weeping for the Negro race, for it is inevitable that intelligent Negroes are likely to be psychologically touchy. As you know, this is not solely a Negro characteristic. Probably ninety-nine out of the hundred human beings, anywhere and everywhere, have been conditioned by circumstances to be touchy about something.

Now it is a great deal to ask of Negroes who have borne up so nobly under inconceivable injustices, not to be unduly touchy. Yet it seems to me extremely important that your race rise to difficult heights and prove itself above trivialities.”

Marjorie pointed out that The Yearling’s time period, 1870-71, called for the “n” word.“It would have been an unpardonable anachronism to have used the word ‘Negro” instead, in a book of this date.”

This was the stronger argument; evidently, she could not hear the condescension in her chief message: “don’t be so touchy.” That message echoed Zora’s attitude; It’s possible that in 1946, Marjorie was taking cues from the friend who first galvanized her.

In May, the lawsuit trial occurred, with public support going to Marjorie. (The saga would drag out two more years behind closed doors, ending in a kind of stalemate.) Marjorie was pleased when she heard Zora had written to a friend:

“I could have saved all kinds of trouble if she [Marjorie] had just plain let me kill that poor white trash” who initiated the lawsuit. “If you hear of the tramp getting a heavy load of rock salt and fat-back in her rump, and I happen to be in Fla at the time, you will know who loaded the shell…”

Later years

The few extant letters between Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Zora Neale Hurston fall away after the trial. In 1947, Zora moved to Honduras for research, and Marjorie bought a new writing retreat in Van Hornesville, New York. She continued arguing for civil rights.

In 1948, Scribners published Zora’s last novel, Seraph on the Suwanee, dedicated to Mary Holland, wife of Florida’s former governor and U.S. Senator Spessard Holland, and Marjorie. (All of Zora’s books were dedicated to white friends and patrons.)

“I am praying that this book will have a big sale so that I can return the sum you so generously loaned me,” Zora wrote Marjorie, indicating her tenuous financial state.

That year, she had been arrested in New York and charged with molesting a ten-year-old boy; the charge was dropped after she proved she had been in Honduras. Marjorie was struggling in other ways; ill health, complicated by alcoholism, hampered progress on her last novel. She died in 1953, a year following The Sojourner’s publication.

After Marjorie’s death, Zora wrote to Mary Holland. “I am deprived of the warmth of the association, and … I feel that I failed her in her last extremity.”

Marjorie had told Zora she was ill, but by then, Zora couldn’t have come to Marjorie’s aid. She had no car. “I could not bear to admit it to her,” Zora confided, “lest she feel sorry for me.”

Contributed by Ann McCutchan. Ann is the author of six books of memoir, essay, and biography. The founding director of the University of Wyoming Creative Writing MFA program, she was also a professor of creative writing at the University of North Texas and editor of American Literary Review. Awards and fellowships have come from the Rockefeller Foundation, Cornell University, the MacDowell Colony, and others. For more information, visit AnnMcCutchan.com.

. . . . . . . . .

A note from Nava, Literary Ladies Guide: It’s bit of irony that Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, so renowned in her heyday, is somewhat forgotten, while Zora Neale Hurston is widely read, studied, and, if I might go so far, the subject of literary worship today. I recently read (and thoroughly enjoyed) The Life She Wished to Live by Ann McCutchan.

Yet when I talked about what I was reading, even to bookish friends, the name Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings didn’t seem familiar. “The author of The Yearling,” I prompted, to silence or blank stares. “It won a Pulitzer Prize,” I persisted. “There was a movie about her starring Mary Steenburgen a few years ago — Cross Creek.” That seemed to ring some distant bells.

In her time, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was a household name, right up there (or close) with Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, with whom she shared the legendary editor, Maxwell Perkins of Scribner’s. This prompts the question (and informs part of the mission of Literary Ladies Guide), why do some worthy authors fall into relative obscurity?

On the other hand, how is it that other authors, forgotten by the end of their lives, once again become literary staples? That’s certainly true for Zora, and well deserved, as she was a wonderful, one-of-a-kind writer. The only sad part is that she struggled mightily all her career with financial solvency, wanting only to make enough to comfortably practice her art.

I particularly enjoyed the portions of The Life She Wished to Live detailing Rawlings’ friendship with Zora, a portion of which has been presented in the article above. Getting to know and admire Zora, her boisterous, proud fellow writer, sparked Rawlings’ personal reckoning with race.

Whether one is familiar with Rawlings or not, The Life She Wished to Live is a glorious read, highlighting the process behind crafting books that have both literary and commercial merit, as hers did. This biography takes an unflinching look at the strengths and weaknesses, the triumphs and failings, the mistakes and perseverance — all necessary components of Rawlings’ richly creative life.

More literary friendships

- George Eliot & Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Virginia Woolf & Vita Sackville-West

- Lillian Hellman & Dorothy Parker

Dear Ms. McCutchan, great article on Zora and Marjorie. I wonder if you can assist me in my search. Barbara Speisman (former professor of English at FAMU in Tallahassee FL) wrote a play called “A Tea with Zora and Marjorie.” I am trying to a purchase a script for a possible production in Vero Beach for our Historical Society. Might you have any idea how I can proceed in my search?

Thanks

Daniel Kroger

Daniel, thanks for your inquiry. I’ll see if I can get Ann McCutchan to respond to you.

Thank you for asking, Daniel. I’ve sent you a reply via email. Anyone else interested in obtaining the script can email me privately: ann@annmccutchan.com Thanks again!

What a beautiful friendship between these two ladies. Thank you for introducing me to Majorie and showing me more of why Zora is still my favorite Author.

Thank you for your comment, Lisa. It’s wonderful to discover new authors and to rediscover what makes us love our favorite writers. I’m also a huge Zora fan and am about to delve into this new biography of Marjorie, from which this article is adapted.

What a fantastic article. I appreciated this depiction of the complexity of two brilliant writers and the willingness of Rawlings to change and expand her preconceived notions.

Thanks for your comment, Lynne. It’s fascinating to examine such friendships when racial politics is involved. One of my former interns wrote a post on the friendship of Zora and Fannie Hurst. It’s not nearly as in depth and well-researched as this one, but It’s interesting to note that Zora started out as an employee of Fannie’s. Today, Zora’s reputation is cemented, while who still reads Fannie Hurst, who was one of the most successful writers of her time? Probably close to no one. https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/literary-musings/fannie-hurst-zora-neale-hurston-a-literary-friendship/

Lynne, I’m so glad you enjoyed the article. Thank you! Meeting Zora was a real “come to Jesus” event for Marjorie, and it was exciting to document it.