Should These Women Authors Be Cancelled?

By Nava Atlas | On January 16, 2025 | Comments (0)

In pondering whether certain classic women authors should or shouldn’t be cancelled for holding abhorrent views I’m not advocating for or against; just musing on this vexing question.

Recently, Lynne Weiss, a contributor to this site, asked me what I’m going to do about Alice Munro. Given the magnitude of Munro’s recent posthumous controversy, I told Lynne I’m not going to do anything. I never got around to reading anything by Munro, truth be told, so it will be easy for me to continue to ignore her.

Then, in the past week, I keep seeing news stories about a certain male author who is getting into more and more trouble More women are coming forward with allegations. I don’t want to say who it is, since he’s still living.

All of this has gotten me to thinking about other women authors who were found to hold abhorrent views (or whose views have become abhorrent to contemporary sensibilities). Should we stop reading them? Should certain things be overlooked if the author left this earth with more in the good column than the bad? Again, this is not for me to decide.

This list makes me vacillate. I could live without some of these writers; others, ouch! it would be tough to give up. It’s the old quandary of separating the art from the artist.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Little House on the (Controversial) Prairie

Thinking about this subject brings to mind something I shared on Literary Ladies’ Facebook page in 2017 when it was Laura Ingalls Wilder’s 150th birthday, an article in Smithsonian magazine, “The Little House on the Prairie was Built on Native American Land.” I simply shared it, I didn’t editorialize But FB page followers, dozens of them, pretty much freaked out and were mad both at me and at Smithsonian.

Here’s a screen shot sampling some of the comments (names and identities redacted):

Some of the comments was of the “she was a product of her time” variety. I wasn’t going to get further into the fray and I’m never one to tell people how or what to think but as an argument, that’s a weak one. Louisa May Alcott, for example, was also “a product of her time,” and she was a feminist and abolitionist.

But then, someone commented on the Substack iteration of this post and informed me that Louisa, who I thought was so sainted, expressed anti-Irish sentiment. Sigh, even Louisa May Alcott isn’t perfect.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Edith Wharton, Antisemite?

Edith Wharton (1862 – 1937) was a wealthy heiress and a product of New York high society, never wanting for anything — except perhaps happiness.

After divorcing Teddy Wharton in 1913, Edith moved to France, which was on the brink of entering World War I. Upon the outbreak of the war, she immediately plunged into relief work. Among her accomplishments were feeding and housing hundreds of child refugees, establishing hostels for other refugees; and assisting wounded soldiers and struggling families.

For her war relief efforts, Wharton received one of France’s highest honors, the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Yet for all her compassion for war refugees, wounded soldiers, and orphaned children, Edith Wharton made no secret of her antisemitism. It was manifested in some of the characters in her books and in her correspondence.

The Jewish Federation of the Berkshires in Great Barrington (a neighboring town of Lenox, home to the palatial home Edith built), co-sponsored an event with the Mount (in neighboring Lenox, MA, a few years ago, “Edith Wharton’s Anti-Semitism: A Consideration.”

It’s hard to square those two sides of her, which coexisted in one talented, energetic, and complicated woman.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, eugenicist?

This one is disappointing and surprising, given how progressive Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860 – 1935) in so many other ways. She’s best remembered for the long short story on the (mis)treatment of postpartum depression, The Yellow Wallpaper, a women’s studies staple.

She was also one of the leading activists in the late 19th and early 20th century American women’s movement, and her nonfiction works (notably Women and Economics) details how women’s lives are impacted by social and economic bias are still (sadly) relevant.

It’s jarring to learn about some of Charlotte’s views on race and immigration. Some of her views in published essays were incredibly racist. And she held rather nationalistic views for someone so dedicated to equality. She had harsh words at times for immigrants, for example, writing that they diluted the “reproductive purity” of Americans of British decent. She famously said of herself “I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything,” and has been labeled a “eugenics feminist.”

Dorothy Canfield Fisher, whose life and work overlapped with Gilman’s was quite popular the 20th century, has also come under scrutiny for her possible sympathies with eugenics.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Colonialism in Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa

Out of Africa by Isak Dinesen (1885 – 1962; pen name of Danish writer Karen Blixen) is a 1937 memoir of her years in Africa, 1914 to 1931. She owned a 4,000-acre coffee plantation in the hills outside of Nairobi, Kenya. This memoir was made famous by the 1985 Oscar-winning film starring Meryl Streep as Dinesen and Robert Redford as her fickle lover, Denys Finch-Hatton.

No one disputes the literary merit of Out of Africa. But in recent years, it has been subject of harsh reconsideration through the lens of decolonization. A 2017 essay in Quartz Africa by Abdi Natif Dahir, “Celebrating Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa Shows Why White Savior Tropes Still Exist,” argues:

“Since the publication of Blixen’s book in 1937, she has remained an important—and lasting—fixture in the study of Kenya’s colonial history … Ultimately, Blixen draws a hierarchy of life in which Africans have no place, in which she is the interlocutor of both ‘native’ and nature, and where ‘white men fill in the mind of the Natives the place that is, in the mind of the white men, filled by the idea of God.’”

And her biography on Post Colonial Studies states:

“Criticism of her work frequently shifts from admiration of her form to outrage at her portrayal of Africans. Karen Blixen’s complicated life and work continue to be studied, debated, and questioned in light of both the colonial society she inhabited and the modern reality of a postcolonial world.”

I rewatched the film last year, and whether because of today’s more critical lens on colonialism (really, it’s terrible to romanticize it) or that it’s simply slow as molasses, it didn’t hold up at all for me.

. . . . . . . . . . .

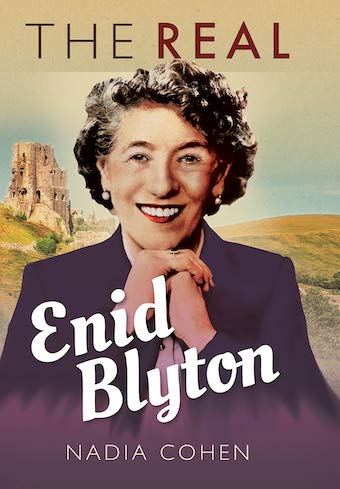

Enid Blyton: Offensive in all possible ways

Enid Blyton isn’t quite as known and read in the U.S. as she is (or was) in her home country, England, where she was once a wildly popular children’s book writer. And apparently, in England’s colonies. Literary Ladies Guide contributor Melanie Kumar and her contemporaries were fans of Blyton’s adventurous tales growing up in India. As an adult, reconsidered her views on this writer. She writes:

“Quite often in life, the innocence and idealism of one’s childhood years are intruded upon by the realities and pragmatism of adult life. The author in question is Enid Blyton, who was called “a racist, sexist, homophobe and not a well-regarded writer,” by the members of the Royal Mint, who in 2019 blocked attempts to give her a commemorative coin.

When one is forced to reckon with the labeling of a favorite author of one’s childhood, there will necessarily need to be a dialogue with the past to find a balance with the present. The issue resurfaced when the UK-based charity, English Heritage, in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement, decided to update its website with information on Enid Blyton.

The website now states that Blyton’s work has been criticized during her lifetime and after, ‘for its racism, xenophobia, and literary merit.’ Read the rest of Melanie’s essay, “When the Past Clashes with the Present: Reminiscences of Enid Blyton.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Of course, many other brilliant creative artists and writers, male and female, were jerks (or worse) in their personal lives. Should we avert our eyes when passing Picasso’s paintings in practically every museum on the planet? Again, I’m not saying that the writers above should or shouldn’t be canceled or ignored. We all have the freedom to read or not read who we choose.

My final question is whether we judge female jerks more harshly than their male counterparts. Read the thoughtful reader comments on the Substack iteration of this post, and feel free to comment below as well. The consensus seems to be: don’t cancel, but it’s good to know the good, the bad, and the ugly when it comes to writers.

One final thought: I have no problem cancelling male authors who have done worse than hold abhorrent views and who have caused actual physical and psychological harm to others.

Leave a Reply