5 Early English Women Writers to Discover

By Francis Booth | On February 1, 2021 | Updated February 21, 2023 | Comments (1)

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf espoused the cause of the playwright and novelist Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689) as the great precursor of free women writers — though the first book in English was written by Julian of Norwich.

The first autobiography was written by Margery Kempe, the first playwright and female poet since antiquity was Hrotsvitha, and the first professional woman writer was probably Christine of Pizan. And we can’t leave out Sappho, the ancient Greek poet.

Presented here are five early English women writers who may not be as well known as Aphra Behn, though each came before her, and set the stage for those who came after — Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Jane Anger, Æmalia Lanyer, and Margaret Cavendish.

Excerpted from Killing the Angel: Early British Transgressive Women Writers ©2021 by Francis Booth. Reprinted by permission.

. . . . . . . . .

Julian of Norwich

The first book written in the modern English language, Revelations of Divine Love, was begun in 1373 by a woman: the abbess Julian of Norwich; it famously repeats the phrase, ‘all shall be well and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.’ Like some of her predecessors and successors, Julian transgressively insisted that being a woman was no bar to writing about the love of God. ‘But for I am a woman should I therefore live that I should not tell you the goodness of God?’

Following her near death from a serious illness at the age of thirty, Julian began to receive revelations or ‘Shewings’ which she believed came straight from God without any ‘mean’ [intermediary].

This transgresses, as do the revelations of all the female mystics, the Catholic idea that God would only speak to the people through a male priest, and in Latin at that. It was men like Luther and Calvin objecting to this idea that led to the Reformation and Protestantism, though the Wycliffe and Tyndale Bibles in English and the Lollards of the late fourteenth century, Julian’s contemporaries, had preceded them. Like other female mystics, Julian stressed the Virgin Mary’s status as the most perfect human; a woman superior in grace to any man.

In this [Shewing] He brought our blessed Lady to my understanding. I saw her ghostly, in bodily likeness: a simple maid and a meek, young of age and little waxen above a child, in the stature that she was when she conceived. Also God shewed in part the wisdom and the truth of her soul: wherein I understood the reverent beholding in which she beheld her God and Maker, marvelling with great reverence that He would be born of her that was a simple creature of His making. . . I understood soothly that she is more than all that God made beneath her in worthiness and grace; for above her is nothing that is made but the blessed [Manhood] of Christ.

. . . . . . . . .

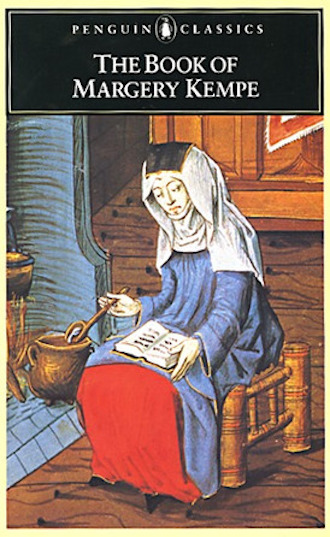

Margery Kempe

Shortly after Julian wrote the first book in English, Margery Kempe began a work in 1436 that also transgressed ideas of what a woman should do and say, in what would become the first autobiography in English: compiled over many years it became known simply as The Book of Margery Kempe.

As she makes clear, Kempe could neither read nor write and struggled to find someone to write down her experiences. Kempe eventually found a priest who was willing to write it out legibly from the various existing badly-written sections, ‘asking him to write this book and never to reveal it as long as she lived, granting him a great sum of money for his labour.’

Because of the ad hoc nature of its composition, ‘this book is not written in order, every thing after another as it was done, but just as the matter came to this creature’s mind when it was to be written down, for it was so long before it was written that she had forgotten the time and the order when things occurred.’

Kempe refers to herself throughout in the third person, mostly as ‘this creature.’ Like Julian and the other mystics she claims her revelations came directly from God, after she had been led astray by devils.

‘She slandered her husband, her friends, and her own self. She spoke many sharp and reproving words; she recognized no virtue nor goodness; she desired all wickedness.’ Jesus then appeared to her, ‘clad in a mantle of purple silk, sitting upon her bedside.’ After this Margery wanted to devote herself entirely to God, at the expense of sexual relations with her husband; transgressively she refuses her husband his conjugal rights.

And after this time she never had any desire to have sexual intercourse with her husband, for paying the debt of matrimony was so abominable to her that she would rather, she thought, have eaten and drunk the ooze and muck in the gutter than consent to intercourse.

Kempe wants to make a vow of chastity and regrets being married. ‘Ah, Lord, maidens are now dancing merrily in heaven. Shall I not do so? Because I am no virgin, lack of virginity is now great sorrow to me.’ But God forgives her. ‘Ah, daughter, how often have I told you that your sins are forgiven you and that we are united.’ But her husband has become so afraid that he does not even try to have sex with her anymore:

… Then she said with great sorrow, ‘Truly, I would rather see you being killed, than that we should turn back to our un-cleanness.’

And he replied, ‘You are no good wife.’

And then she asked her husband what was the reason that he had not made love to her for the last eight weeks, since she lay with him every night in his bed. And he said that he was made so afraid when he would have touched her, that he dared do no more.

. . . . . . . . .

Jane Anger

Like many of the works written by transgressive women, Her Protection for Women (1585) by Jane Anger (1560 – 1600) was addressed explicitly to an audience of other women. It was probably the first book-length defence of women’s place in society to be published in English. In 1558, the Scots preacher John Knox had published The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. The appropriately-named Anger’s book was the first blast of women in return and very angry indeed.

To all Women in general,

and gentle Reader whatsoever.

FIE on the falshood of men, whose minds go oft a madding, & whose tongues can not so soon be wagging, but straight they fall a railing. Was there ever any so abused, so slandered, so railed upon, or so wickedly handled undeservedly, as are we women? . . But judge what the cause should be, of this their so great malice towards simple women.

Doubtless the weakness of our wits, and our honest bashfulness, by reason whereof they suppose that there is not one amongst us who can, or dare reprove their slanders and false reproaches: their slanderous tongues are so short, and the time wherein they have lavished out their words freely, hath been so long, that they know we cannot catch hold of them to pull them out, and they think we will not write to reprove their lying lips.

Like other transgressive, pre-feminist writers going back to Hildegard of Bingen, Anger claims that Eve’s original transgression is more than balanced by the Virgin Mary’s grace, bestowed upon her by God. Again, she is specifically addressing a female audience.

And now (seeing I speak to none but to you which are of mine own Sex,) give me leave like a scholar to prove our wisdom more excellent then theirs, though I never knew what sophistry meant. There is no wisdom but it comes by grace, this is a principle, & Contra principium non est disputandum: but grace was first given to a woman, because to our lady: which premises conclude that women are wise. Now Primum est optimum, & therefore women are wiser than men.

GOD making woman of man’s flesh, that she might be purer then he, doth evidently show, how far we women are more excellent then men. Our bodies are fruitful, whereby the world increaseth, and our care wonderful, by which man is preserved. From woman sprang man’s salvation. A woman was the first that believed, & a woman likewise the first that repented of sin.

. . . . . . . . .

Æmelia Lanyer

Æmalia Lanyer, or Emilia Lanier (1569 – 1645), is said to be the first English woman to publish a book, though she was in fact preceded by Isabella Whitney; but Whitney only published a pamphlet, mostly comprising poetry written by others, including the Cornish woman Anne Dowriche, and the Scot Elizabeth Melville.

Nevertheless, Lanier was the first British woman to assert her status as a professional writer, though her book of poems Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, published in 1611 when she was forty-two, is advertised as being by a wife. ‘Written by Mistris Æmilia Lanyer, Wife to Captaine Alfonso Lanyer, Seruant to the Kings Majestie.’

The book is addressed specifically to women and dedicated to several female aristocrats, seeking their patronage woman to woman, begging pardon for her ‘defects.’ They include a dedication ‘To the Queenes most Excellent Majestie’.

Renowned Empresse, and great Britaines Queene,

Most gratious Mother of succeeding Kings;

Vouchsafe to view that which is seldome seene,

A Womans writing of diuinest things:

Reade it faire Queene, though it defectiue be,

Your Excellence can grace both It and Mee. . .

And since all Arts at first from Nature came,

That goodly Creature, Mother of Perfection,

Whom Ioues almighty hand at first did frame,

Taking both her and hers in his protection:

Why should not She now grace my barren Muse,

And in a Woman all defects excuse.

Lanier was born Aemilia Bassano, a member of the Venetian Bassano family of musical instrument makers who lived and worked in London and has been a candidate for Shakespeare’s Dark Lady. The thrust of her book is female virtue and obedience to God’s will; in this sense she is no bad girl. But, like Jane Anger before her and Margaret Cavendish later, Lanier complains that it is unfair that, because of Eve, ‘we (poore women) must endure it all.’ Eve cannot be blamed for man’s fall.

And ‘If Eue did erre, it was for knowledge sake,’ and in any case, Adam ate too: ‘The fruit beeing faire perswaded him to fall: / No subtill Serpents falshood did betray him.’ Adam wanted to share in the knowledge which eating the fruit gave Eve; human knowledge comes from Eve but men have claimed it. ‘Men will boast of Knowledge, which he tooke / From Eues faire hand, as from a learned Booke.’ The evil was not in Eve, who was, quite literally, made from Adam, but in men’s betrayal of God’s intentions.

Like many other women writers, Lanier extols at length the obedient virtue of the Virgin Mary, who more than compensates for any sins of Eve. But, also like other women writers, she also extols strong women in history who have physically overcome powerful men, Like the Scythian Women, or Amazons.

Lanier also mentions with approval the biblical judge and prophet Deborah and the great pre-feminist Judith, who cut off the head of Holofernes before he could rape her and so set her people free, though what Lanier is celebrating in Judith’s act is a woman defeating a man who has ignored God’s will rather than a woman’s:

Yea Judeth had the powre likewise to queale

Proud Holifernes, that the just might see

What small defence vaine pride and greatnesse hath

Against the weapons of Gods word and faith.

. . . . . . . . .

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle

Men are so Unconscionable and Cruel against us, as they Endeavour to Bar us of all Sorts or Kinds of Liberty, as not to Suffer us Freely to Associate amongst our Own Sex, but would fain Bury us in their Houses or Beds, as in a Grave; the truth is, we Live like Bats or Owls, Labour like Beasts, and Die like Worms.

— Margaret Cavendish, To All Noble and Worthy Ladies

Also writing for an exclusively female audience and also angry at men was the eccentric Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle (1623 – 1673), whom Virginia Woolf called a ‘giant cucumber,’ which ‘had spread itself over all the roses and carnations in the garden and choked them to death.’ She addressed some of her writings explicitly to ‘ladies.’ Her Poems and Fancies of 1653 begins:

Noble, Worthy Ladies, Condemn me not as a dishonour of your Sex, for setting forth this Work; for it is harmless and free from all dishonesty; I will not say from Vanity: for that is so natural to our Sex, as it were unnatural, not to be so. Besides, Poetry, which is built upon Fancy, Women may claim, as a work belonging most properly to themselves.

Cavendish asserts here that poetry is the natural realm of women’s imagination. In the introduction to her proto-science fiction novel The Blazing World, she also addresses a female audience and asserts her right to write whatever she pleases; if the present world is not to her taste she has the right to invent one that is and to be the mistress of it.

And if (Noble Ladies) you should chance to take pleasure in reading these Fancies, I shall account myself a Happy Creatoress: If not, I must be content to live a Melancholy Life in my own World . . . I am not Covetous, but as Ambitious as ever any of my Sex was, is, or can be; which is the cause, That though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second; yet, I will endeavour to be, Margaret the First: and, though I have neither Power, Time nor Occasion, to be a great Conqueror, like Alexander, or Cesar; yet, rather than not be Mistress of a World, since Fortune and the Fates would give me none, I have made One of my own.

Cavendish transgressively published under her own name: not only fiction but scientific and philosophical works, including many short pieces on the natural sciences, and especially about the atom, written in verse ‘because I thought errors might better pass there than in prose – since poets write most fiction, and fiction is not given for truth, but pastime – and I fear my atoms will be as small pastime as themselves, for nothing can be less than an atom.’

Cavendish knew philosophers and scientists like Descartes and Thomas Hobbes and in 1667 she was the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, which did not admit women until 1945. Like several other early transgressive writers, Cavendish assumes that as a woman she will be subjected to harsher criticism than a male writer, not just by men but by women too.

Unlike Joan of Arc and the thousands of European ‘witches,’ Cavendish was not literally burned at the stake and unlike the French writer Olympe de Gouges she was not sent to the guillotine; she stayed out of politics and though she was hardly the Angel of the House she mostly stayed out of trouble. But like several early women writers Cavendish was keen to stir women to action, to make the best of themselves and ignore men’s efforts to keep them down.

Learn more about the transgressive writing of Margaret Cavendish.

. . . . . . . . . .

Killing the Angel on Amazon US*

Killing the Angel on Amazon UK*

. . . . . . . . . . .

RELATED CONTENT

- The Matchless Orinda — Early English Poet & Playwright Katherine Philips

- Elizabeth Cary: Early English Poet, Dramatist, & Scholar

- Olympe de Gouges: An Introduction to Her Life & Work

- Susanne Centlivre, English Poet & Playwright

- The Scandalous, Sexually Explicit Writings of Aphra Behn

- Advice to Young Ladies on Reading Novels

Contributed by Francis Booth,* the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England. He is currently working on High Collars and Monocles: Interwar Novels by Female Couples.

. . . . . . . . .

*This is an Amazon Affiliate link. If a product is purchased by linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps maintain our site and helps it to continue growing!

Wishing luck to your work — and an url for a book on the earliest English woman writer — AB

https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-0364-1266-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Breeze