Evvie by Vera Caspary (1960)

By Francis Booth | On April 8, 2022 | Updated August 28, 2022 | Comments (0)

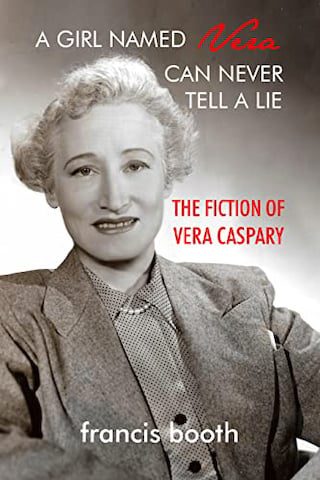

Evvie (1960) is a sophisticated thriller by the remarkably prolific and unfairly forgotten novelist and screenwriter Vera Caspary. This appreciation and analysis of Evvie is excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

The publisher’s copy described the novel succinctly:

“This big, bursting novel of the roaring Twenties – and of two girls who believed that love and art could save the world, if not themselves – is in our view the best book that Vera Caspary has ever written, not forgetting Laura.

Evvie Ashton and Louise Goodman shared a studio in Chicago in 1928, the age of “the girl.” Louise was a successful advertising copywriter in love with her boss. Evvie, married and divorced at seventeen, beautiful, artistic, was living on her “alimony”. Men found her irresistible – just as she found men. She painted, she danced, she read a great deal, and could discuss anything by repeating what her admirers had said.

But, in the midst of all the gaiety, Evvie and Louise found their lives becoming desperately complicated. Yet neither sensed that tragedy was to strike, until a horrible crime involving friends and families, strays and unknowns, the cream and the dregs of Chicago, gave the newspapers a field day.

The reader, mesmerized by the constantly mounting suspense, follows the involvements, the revelations and the shocking relationships of all those touched by the crime. But it is Evvie herself who will haunt the reader’s memory for a long, long time.”

Reviews of this novel were overwhelmingly positive, highlighting the author’s talent at weaving suspense into a compelling narrative of the lives of two freedom-loving young women in the Roaring Twenties. Here’s a snippet of one such typical review:

“That same Vera Caspary who wrote the exciting Laura some years ago has a new murder-suspense story, Evvie, which in addition to skillful suspense provides a detailed account of two free and easy successful business gals in the Chicago of the Twenties. Evvie is so attractive and the evocation of her period so nostalgic that the reader is tempted to forget what a good mystery the author makes of who killed Evvie.” (Rocky Mountain Evening Telegram, September 18, 1960)

Focused on “faint praise”

Yet despite numerous glowing reviews, Caspary chose to focus on the “faint praise,” as she puts it, in this passage from her memoir, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (1979):

“The novel Evvie, which I still think one of my best, was greeted with faint praise. In Chicago, Fanny Butcher came out of retirement to declare it obscene—ironic judgment from today’s point of view, since there are no graphic descriptions, and the most explicit allusions are in a scene in which two naked girls discuss sex.

Since Laura I’ve been typecast as a suspense writer and, to my own dismay, may have fallen into the trap. Evvie was born of a situation involving murder. But instead of keeping to the mystery formula I indulged in elements far out of that field of fiction. There was only one murder. It came late, halfway through the story.

Evvie is a picture of the lives of girls in the twenties, drawn quite honestly from my own experiences. More clearly than in any of my other books it defines the changing position of women at a time when tradition was sturdier, inhibition more binding than in these later years when girls declare independence by demanding entrance to men’s colleges, sports, and bars. Evvie was begun in London, continued in New York, finished in Beverly Hills, proofed in Paris.”

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . .

Caspary’s characterization of Fanny Butcher’s review is rather unfair; perhaps she misremembered it: the review is not exactly glowing but Butcher had been reviewing books for nearly 40 years at this time and can perhaps be forgiven for her cynicism regarding books written to be popular.

Butcher was hardly anti-Caspary: her review of The White Girl thirty years earlier had been very positive. And, despite Butcher’s reservations, her review does make one want to read the novel ,though apparently it did not make enough people want to read it to make Evvie a bestseller.

Butcher doesn’t call the novel obscene at all and she had not in fact retired at this time. The review in question, from the Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1960, titled “Setting: Chicago 1920; Flavor: Beatnik 1960” concludes:

“Nobody is going to be deterred from reading Evvie for technical reasons, however, nor, in these days of the policy of the open door to every bedroom, by the heroine’s inability to deny herself a man, any man, even her best friend’s beloved. And Louise’s way of telling the story has a kind of entrancing glitter. So Evvie will probably be on the bestseller lists and be bought for the movies before the author gets her first royalty check.”

One of Caspary’s best novels

With hindsight, Caspary was right about Evvie: it is one of her best novels, possibly the best of them all and deserves to be as well-known as Laura and Bedelia. But, despite Butcher’s predictions, it never was on the bestseller lists, never was bought for the movies and is almost forgotten today.

It is a particular shame that it was never made into a film; the fact that the murder occurs and the heroine disappears halfway through would have been no barrier: Hitchcock did exactly that in Psycho, also released in 1960. And the year after Evvie, 1961, Caspary’s next novel, Bachelor in Paradise, was made into a film.

Perhaps by that time, after the death of film noir, producers were looking for more frothy material – Caspary could certainly do frothy; she did so with Out of the Blue in 1947, again with Bachelor, and in her light, romantic screenplays and original treatments for the movies. But not with Evvie. Evvie was serious for her — serious and personal, perhaps even cathartic in its intensely personal autobiographical elements.

A complex and autobiographical novel

Evvie is a complex novel and in my categorization of Caspary’s works into psycho-thrillers and coming of age novels it could have counted as either: its first sentence is “Horror attended the death of girlhood.”

The narrator, Louise, despite her high-earning job and the respect she gets from men in the office, is reluctant to leave girlhood behind and come of age. “With the responsibilities of my job, the help I gave my mother, with life insurance and the right to vote for a president in November, I was adult, old enough to give up girlhood. But how? I loved being a girl, I did not want to change. Maturity looked too stolid.”

Along with the earlier Thelma, Evvie is unique among Caspary’s works in that it has a first-person narration where the narrator is not the title character, like Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca.

This trope is also reminiscent of Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone – we have already seen how heavily influenced Caspary was by Collins’ other novels – where Rachel Verinder is the central character but never the narrator; like Collins’ Rachel and like her namesake in du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel, Evvie is only seen through the eyes of other people.

Evvie is also unusual in being by far by far the most autobiographical of Caspary’s works, apart from her actual autobiography – the narrator is called Louise, Caspary’s middle name, in case we had any doubts. Louise is not so much a Caspary woman as a lightly fictionalized version of Caspary herself.

In fact, we might almost say that the title of the novel is a red herring: it really should have been called Louise; Evvie herself is almost as absent a presence as Rebecca in du Maurier’s eponymous novel.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie is available

on Amazon (US) and Amazon (UK)

. . . . . . . . . .

A late 1920s Chicago setting

Although Evvie was published in 1960, when Caspary was sixty-one years old, the setting is a lovingly described late 1920s Chicago, as it was in the much earlier The White Girl and Music in the Street and would be again much later in The Dreamers. At this time and place Caspary was working in a man’s world as a copywriter and designing and selling correspondence courses while writing a novel in her spare time, as is Louise.

But, like Caspary herself, Louise Goodman is regarded as one of the boys (a good man). “They put on a show of gallantry and when they used off-color expressions smiled toward me furtively. Someone would always remark that you could say anything in front of Louise, she was a hell of a good sport.”

At work, because they are not obsessed with Louise’s looks, not scared of her, men feel able to give Louise backhanded compliments: “I’ve never known a girl like you. You’re not pretty but you got a wonderful line and you’re dynamite.” Evvie, who has no job and lives off the alimony her stepfather gets, is a painter – the two girls live in her studio apartment – and the pretty one of the pair; next to her Louise is the plain but smart one.

All the sections of Evvie that describe Louise’s job sound like the reminiscences of Caspary herself, as told in her tales of those 1920s days in her autobiography The Secrets of Grown-ups. Louise’s mother even sounds very much like Caspary’s in her attitude to her daughter’s business career and independence:

“For the life of her Mama could not see how anyone could pay eighty dollars a week to a girl of twenty-two. Yet she was proud. These shreds of information nourished her and my success at the office gave her the chance to brag when ladies at bridge tables wondered why a girl clever enough to earn all that money had not yet found a husband.”

Like Vera Caspary with her Marinoff dance course and Van Vliet photoplay course, Louise Goodman writes correspondence courses for the agency, inventing gurus for whose advice subscribers will pay good money, like the famous Dr. Russell Wadsworth Bryant. But “there was no Dr. Russell Wadsworth Bryant. The names of three New England poets had been strung together to give the sound of culture to E. G. Hamper’s correspondence course. . . My greatest success in the agency had been in the development of the Bryant personality.”

The emergence of the working girl

It is not just in Louise’s job but in her relationship with Carl, one of her bosses in the office, that she is so similar to Caspary, who in her autobiography describes in detail the physically intimate relationship with her own boss, whom she calls simply the Junior Partner.

Louise begins to fall for Carl just as he begins to withdraw; she doesn’t understand the change in his attitude to her until later.

“Each day at the office I waited for some sign of change in Carl’s attitude, some word of praise, some little attention. . . I was tempted to ask if and why he had quit liking me but had no courage to face him with the question. I pitied myself, so a spinster future and the dry life of devotion to my mother.”

Like Caspary herself in the late 1920s, Louise uses every spare minute of her leisure time to write novels and stories. When the Chicago winter is so bad she can’t get to work, Louise only has one thing on her mind: “Wearing two sweaters, a robe and blankets I tried to work on my novel. It was impossible to travel through the snow-piled streets to the office.” This reads like Caspary fondly reminiscing. Even Louise’s description of her literary ethos could be a summary of Caspary’s own positioning of women within her fiction:

“All my tales, whether gaily caparisoned with wealth or morbid in poverty, whether celebrating health or pain (for there are sanatoria and cemeteries as well as ballrooms), tell of man’s reliance upon woman, his need, blindness, and final recognition. In its many beginnings, mutations and styles of narration, my story always concerns man’s search for the sympathy and satisfaction that only the heroine can bestow.”

Both the time around and just after Evvie’s publication in 1960 and the time of its setting in the 1920s were in their different ways the era of the working girl: independent, sexually aware and enjoying her freedom – though the working girls of the 1960s enjoyed sexual freedom far more than those of the 1920s.

The first wave of novels about these freedom-loving, happily unmarried working women started appearing in the 1920s. A second wave started appearing at the end of the 1950s with Rona Jaffe’s The Best of Everything in 1958, followed by Evvie in 1960 and then Mary McCarthy’s The Group and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, both published in 1963. A passage from Evvie:

“For this was the age of The Girl. We had come out of the back parlor, out of the kitchen and nursery, we turned our backs upon the blackboards, shed aprons and paper cuffs. A war had freed us and given women a new kind of self-respect. The adjective poor no longer preceded the once disreputable working girl. It was honorable, it was jolly, it was even superior to be a career girl. Intellectual young men considered themselves members of a lost generation. For us it was a decade of self-discovery. We held jobs, we voted, we asserted equal independence with men, equal privilege. Best and most decisive in the reshaping of our lives was the money in our pocketbooks.”

The female contraceptive pill was launched in the United States in 1960, and although it wasn’t widely available for a long time, that didn’t stop women claiming sexual equality with men or refusing to wait until after marriage to have sex. It certainly doesn’t stop Evvie and Louise, who have 1960s rather than 1920s sex lives.

Even Evvie’s wealthy and flighty mother does not disapprove. “If you’re not married or engaged, the least you can do is have a bit of fun. But I insist that you use proper contraceptives. Do you know about pessaries? … We could go to London and have you fitted.”

In The Group, Dick tells Dottie to get herself “a pessary;” she doesn’t understand. “‘A female contraceptive, a plug,’ Dick threw out impatiently. ‘You get it from a lady doctor.’” Dick is married – to someone else – and makes Dottie promise not to fall in love with him; no one in “the group” wants naïvely to confuse sex and love. Neither does Louise in Evvie.

“To this day I am grateful that I had my first experience with an honest lover. There were no romantic promises, no vows of permanent devotion, no discussions of marriage. Our generation took lovers with conviction and did not rush off to seek absolution. Nor was I a girl who considered a husband destiny and a wedding the end of all seeking.”

Nevertheless, much later, when the first lover tells Louise he is getting married, she has pangs of regret. “In the mirror I saw the pallid, tear-streaked face of a spinster with no more in life than a job and the memory of a youthful affair.”

Frank, cynical, and explicit

In its frankness, cynicism and explicitness about sex, Evvie feels as though it was written sometime in the middle 1960s, in the time of Betty Friedan and Helen Gurley Brown, in the age of the contraceptive pill, rather than at the end of the 1950s.

But according to Caspary’s autobiography, there was indeed a similar frankness about sex in the big city when she moved to New York in the 1920s, when she was in her twenties; Caspary seems herself at that time to have lived a life very similar to that of Louise and Evvie, according to The Secrets of Grown-Ups:

“Sex was the backbone of conversation among intellectuals and their imitators. In uptown apartments as well as Greenwich Village studios, among girls and girls, men and men, men and girls, with lovers, potential lovers and rejected lovers; conversation was the popular aphrodisiac.

We all had a smattering of kindergarten Freud and at the drop of a chemise would analyze our own and our friends’ affairs. Sexual inhibition was to be avoided like pregnancy and a repressed libido shunned like a dose of clap. No one used the term sexual revolution, but certainly a generation had risen in revolt against the Victorian restraints of its parents. Sex had become the dominating theme of novels, plays, sermons, lectures, jokes, and pranks.”

Evvie was married and divorced young, so she isn’t a virgin at the start of the story. But she doesn’t at first let her latest lover – the mystery lover with whom she is obsessed but whose name Louise and we, the reader do not yet know – know about her sexual appetites.

Later Evvie feels she has to confess to him about her urges and then she confess her confession to Louise, who is Evvie’s confidante in everything but the man’s name: “wayward and wanton,” is how she describes herself to him, stealing the words from Louise’s novel, though she denies being obsessed with sex.

“’I said I’d never liked it very much, that I really didn’t care an awful lot about sex. That’s true.’ Sighing again, she waved her cigarette aloft. ‘I never did go crazy about it the way some girls do. At boarding school in Santa Barbara there were girls, simply maniacs.’”

For contrast, Caspary gives the sexually aware Louise and Evvie a mutual friend, Midge, a relatively new recruit to the ranks of Chicago working girls who is shy and virginal, very much unlike them. Midge has a boyfriend who keeps insisting she has sex with him, but Midge is very unsure. “I’ve told him over and over, let’s be good friends, Bob, but don’t ask me to be a common pushover.”

Louise and Evvie try to explain that his attitude is perfectly normal in a young man. “Bob’s in love with you and he honestly believes that sexual completion is an expression of love.” Midge will not relent. They accuse her of cruelty to Bob.

After Evvie’s death, Midge, now a successful newspaper reporter, wastes no opportunities to hit out at the immorality of Evvie and her circle in her paper.

“Last winter Evvie and her sophisticated friends laughed at this country girl for expressing horror at their advanced views of life and sex but today these same ‘bright young people’ are asking themselves what all of their cocktails, jazz, modern philosophy and indiscriminate petting leads to.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Shifting into psycho-thriller mode

Up to this point, Evvie has been simply a more-than-semi-autobiographical story about two young women enjoying free life and free love in the 1920s. Suddenly, mid-chapter, it becomes a psycho-thriller.

Both of the big revelations come at once, though Louise and the reader have already begun to suspect the first revelation: “Only the compulsion to self-deceit could have kept me from noting the signs along that tragic road.”

In the very next paragraph, the M word first appears for the first time as the pace and tone of the story change completely.

“To keep this story rigidly within the limits of my knowledge at that time would stunt its growth. Indirection and subterfuge weave a false mystery. What I shall now tell (out of chronological order) was later confessed in a darkened room.

The terror of its mood is recalled whenever I see bars of unwelcome sunlight force their way through a closed Venetian blind or hear in any voice the echo of desperation. It was in the taut time after the murder when Carl sought my understanding. No other state of mind could have brought about such articulate agony.”

As Caspary later said in her autobiography, quoted above, she had begun writing Evvie as a mystery, but she had “indulged in elements far out of that field of fiction” – she had clearly got carried away with the thinly-veiled autobiography and ended up combining two kinds of narrative in one novel, which upset some critics and readers.

Still, that blending of mystery and psychology is the essence of the psycho-thriller and when we learn that Evvie has been murdered, we care far more about her than we did about Laura because we know so much more about her.

At this stage, we have no idea how or why Evvie was killed; this is the opposite of Laura, where we know exactly how the murder was committed but very little about the murdered woman.

The rest of the novel alternates between psycho and thriller, though there is far more reflection than action, with revelations, flashbacks of details from Louise’s past and Evvie’s diary, which Louise finds in the studio and hides from the police – she had not read it before.

“Betrayal by a man is to be expected, woman’s lot, but she had been my friend, my darling, beloved since childhood. As I walked I scolded her. Resentment was barren for it is futile to rage at the dead; but I had to remind her. There was so much, thousands of secrets, confidences, foolish notions. She had been my first love. I had been caught in that period when a girl gives rapture and worship to her own sex.”

Louise – as Caspary’s mouthpiece – makes clear again that the story, like any narrative, must be unreliable and partial.

“Out of yellowing newspapers as vulgar and lively as this morning’s murder, out of Evvie’s diary and mine this story has been rewoven; out of nostalgia for girlhood, out of snatches of unforgotten conversations, daydreams disinterred, out of tunes and flavors that recall ghosts. I cannot promise that every scene is precisely remembered nor every dialogue true.”

Spoiler ahead

Carl is arrested for Evvie’s murder, though neither he nor Louise have told the police about his relationship with the dead Evvie. But it turns out that Carl didn’t do it, someone else did, someone unlikely, someone we have not even met before: the “pimply” boy who worked at the garage next to the studio and had run errands for Evvie; he had become obsessed with her.

But although this twist is unexpected and unlikely, not to mention disappointing, Caspary has planted plenty of examples of Evvie giving money to disabled beggars and the unfortunate who lined the streets of Chicago in the manner of Chekhov’s gun.

Louise had always been frustrated at Evvie’s indulgent and, as Louise sees it, dangerous habit of talking and giving to waifs and strays, the disabled and the outsiders, of whom the young murderer is one.

This unexpected and unconventional ending is either, according to taste, brilliant or banal and bathetic.

“There was no mystery nor moral to the squalid tale; it had none of the inexorable directness of a contrived detective story, neither the glitter of crime in high places nor the spice of Bohemian transgression.”

As she had in Laura, Caspary comments, meta-fictionally, on the traditional detective story and connects the psycho with the thriller.

“The horror of the case lay in its untruths; all those bright red herrings hailed in the beginning as important clues and found in the end to be no more than reflections of our own guilt.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

Leave a Reply