Vera Caspary’s Bachelor in Paradise (1961): Sex and Bias in the ‘Burbs

By Francis Booth | On February 11, 2022 | Updated August 28, 2022 | Comments (0)

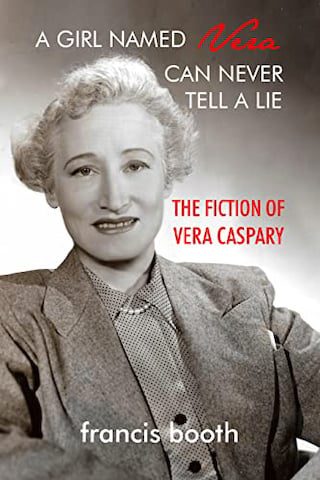

The newly built Los Angeles suburb of Paradise in Vera Caspary’s 1961 novel Bachelor in Paradise is rather like the aspirational estate of Northridge in Caspary’s earlier story “Stranger in the House” (1943). Excerpted from A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie: The Fiction of Vera Caspary by Francis Booth ©2022. Reprinted by permission.

“It is one of those suburbs distinguished in real-estate advertisements by the word exclusive. The residents spend large sums to separate themselves from neighbors whom they meet as often as possible at the Country Club . . . Pedestrians are seldom seen.”

It is also somewhat similar to the setting of Grace Metalious’s 1956 novel Peyton Place (1956), with its simmering suburban sexual tensions among the “simple, well-constructed, one-family dwellings, most of them modeled on Cape Cod lines and painted white with green trim” and to Pepper Street in Shirley Jackson’s The Road Through the Wall (1948), also set in a California suburb.

Trouble in Paradise

The descriptions of the lives of the women in the suburban, middle-class houses in Caspary’s Paradise anticipate Betty Friedan’s explorations of The Feminine Mystique (1963) into the sexual underworld of the women who live in these perfect, fully equipped homes designed to give the modern housewife everything she needs except intellectual and sexual satisfaction.

Paradise Estates, Adam discovered, offered the ultimate in Gracious Living; fully equipped built-in kitchens . . . two ovens to every stove . . . Picture windows, thermostatic all-year temperature control, architecture to suit a variety of purses and every taste.

Eight floor plans were shown in the two-three- and four-bedroom models; all of these could be adapted to any style or period. There were Paradise Regency, Paradise Provincial, Paradise Rancho and Paradise Contempo. In spite of the labels under the pictures the houses looked all the same to Adam. Perhaps, he had the humility to tell himself, his eye had not been trained to subtleties. He could not allow himself too much prejudice.

“Welcome to Paradise, Mr. Niles.”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, American men were very proud of the modern domestic gadgetry that they had worked so hard to buy to make their wives’ lives easier. In July 1959, even President Richard Nixon, in the famous “Kitchen Debate” with Russian President Nikita Khrushchev had been bragging about how the latest technology in Californian kitchens made the American housewife the envy of the world.

Aspirational magazines like Good Housekeeping, in which Caspary first published several of her pieces, and Today’s Woman, for Today’s Homemaker, later subtitled for Young Wives, where Caspary’s Out of the Blue first appeared in 1947, prominently featured full page color ads for these latest, labor-saving domestic gadgets showing suburban housewives beaming with happiness and content. But many of them were not at all not content with their gadgets, their lives and especially with their husbands.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Vera Caspary

Learn more about Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . .

Desperate housewives

In the same year Betty Friedan was also to show in The Feminine Mystique exactly how bored, unsatisfied and unfulfilled was the suburban housewife, descendant of Emma Bovary living a life of quiet desperation behind the picture windows.

“The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night – she was afraid to ask even herself the silent question – ‘is this all?’”

Ten years earlier, in 1953, Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal The Second Sex had been first translated into English and had posed some of the questions Friedan was answering.

“How can a human being in woman’s situation attain fulfillment? What roads are open to her? Which are blocked? How can independence be recovered in a state of dependency? What circumstances limit woman’s liberty and how can they be overcome?”

Communities of “the best sort”

Apart from the undercurrent of sexual dissatisfaction, another unspoken problem in these white, aspirational enclaves was the prevalence of racism and antisemitism, both of which Caspary tackled seriously throughout her life and writing career.

Here she treats things rather more lightly, despite the February 1960 incident in which four Black college students in North Carolina refused to leave a Woolworth’s lunch counter without being served and the March 1960 bomb and gun attack on Temple Beth-Israel in Alabama. Both of these incidents may have happened while she was writing Bachelor.

The first purpose-built conurbations in America were constructed after the Second World War and aimed to provide affordable housing for returning veterans to buy rather than rent. They were called Levittowns after their founder William J. Levitt, who refused to sell the homes to people of color; the Federal Housing Association which loaned the money for their construction included racial covenants in the contracts ensuring that the communities would be segregated.

The realtor for Paradise Estates in Bachelor tells Adam that it is “a community of the best sort.”

These communities were built as white middle class bastions, sheltered from the racial and economic diversity of big cities like Los Angeles, New York and Chicago – Caspary’s three main homes throughout her life and the settings of most of her novels.

The boosterism in the realtor’s paean to Paradise recalls Sinclair Lewis’s much earlier eponymous realtor in Babbitt (1922), set in Zenith, where “American Democracy did not imply any equality of wealth, but did demand a wholesome sameness of thought, dress, painting, morals, and vocabulary.” And race.

. . . . . . . . . .

A Girl Named Vera Can Never Tell a Lie

is available on Amazon (US) and Amazon (UK)

. . . . . . . . . .

A lone bachelor

Adam’s stay in Paradise, where he works from home, breaks the one cardinal rule: there are no men in Paradise during the weekday unless they are sick or retired.

“The male exodus which started at 7 a.m. on Mondays and continued through Friday gave Paradise Estates the atmosphere of a convent whose nuns were allowed habits of varied style and color.”

When the men return at the weekend, they plunge into domestic chores.

“Saturday mornings brought out the usual spate of do-it-yourself husbands in blue jeans, faded khaki and floral shirts. They began like busy bees to repaint, repair, lay bricks, plant perennials.”

To make things worse for himself, Adam is not used to having picture windows and never closes his curtains, so everyone makes it their business to know exactly what he is doing at all times. This has an alarming effect on the wives at home.

“Had Adam been half the man he was these women would have been kindled. Had he been fat or bald or growing his first beard, or partly disabled by a wife, at some distant place, he would have added excitement to their lives; but he was healthy, debonair, violently male and unattached. Local fashions changed. Wide skirts and frilly blouses took the place of blue jeans and old shirts. Curlers were not seen in public.”

To the home-alone women of Paradise, “the season of the bachelor was no less than the advent of an archangel.” They want him not just for sexual purposes but for the domestic do-it-yourself skills all men are assumed to have. “Aggressively domestic” is the way he describes them.

“Since no gadget ever invented for woman’s comfort has displaced man, the female community found many uses for its stay-at-home bachelor.” Adam can never settle down to work for any length of time before the doorbell rings and a neighbor asks for his help, whenever “tires went flat, when motors stalled, bathtubs overflowed, when they needed help with plugs and wires and the common screwdriver.”

With Caspary’s Laura, Bedelia, Evvie and Elizabeth X we had women at the center of a mystery pursued by multiple men, here we have a man who is himself a mystery pursued by multiple women: Dolores, Linda, Rosemary and her siren teenage daughter Patty. Divorces ensue, jealousy and envy are everywhere. One night, in his own house, Adam is assaulted by three separate jealous men.

Then Adam chooses Rosemary and she chooses him back. Both are too cynical to want to get married, so they start an affair.

“Neither believed the affair sinful. It is not adultery when no one is married.”

But it is a shock to the community.

“Had these lovers lived in Greenwich Village, in Paris, London, even in Hollywood or the center of St Louis, one of them could have moved into the other’s house and to hell with the neighbors. But they lived in Paradise and Paradise does not have a climate friendly to the frankly passionate.”

. . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy: Bedelia by Vera Caspary

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

Leave a Reply