Orphans and Boarding Schools: On rereading Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster

By Marcie McCauley | On August 22, 2021 | Updated August 27, 2022 | Comments (0)

The summer I was twelve, I pulled a well-read and worn book from the shelves of the public library and discovered a story that seemed to be told directly to me. Behind the deceptively dull cover of Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster (1912) were letters and drawings that pulled me hard and fast into Judy Abbott’s life—an orphan at boarding school.

So many of my favorite things were combined in this book: orphans and lonely childhoods, girls succeeding against the odds with their studious natures, boarding school and class events, and perhaps most of all, the burgeoning writer’s sensibility that I also enjoyed in Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy (1964).

I borrowed and devoured Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs that very afternoon; I’ve revisited it many times.

Orphan girls

Judy’s orphan status reminded me of other favorite characters, from classics like Emily of New Moon (1923) by L.M. Montgomery, Ballet Shoes (1936) by Noel Streatfeild, and A Little Princess (1905) by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

And later-twentieth-century orphans, too, like Mandy the eponymous heroine of Julie Andrews Edwards’ 1971 novel and Christina in K.M. Peyton’s Flambards (1967).

As a kid with recently divorced parents, relocated a couple of hundred miles from familiar territory, I related to these characters’ dislocation. Pseudo-orphans, girls temporarily separated from family—in Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking (1945) and Joan Aiken’s The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (1962)—also appealed.

Even girls unexpectedly living in single-family households like the March sisters in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1880) — Rose Campbell, in Eight Cousins (1874), was a proper orphan but I hadn’t met her yet.

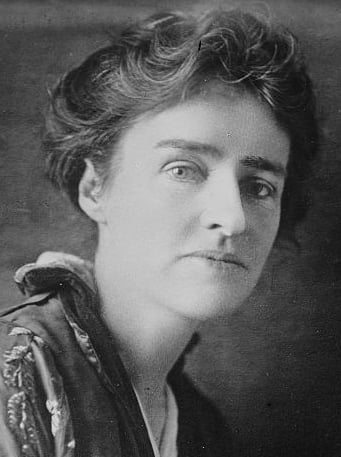

And Judy wasn’t only an orphan, but an orphan keen on rewarding her anonymous benefactor’s investment — not simply surviving, but thriving. The biography of my copy of Daddy-Long-Legs described its author as an orphan, but Jean Webster lived with both parents until she was fifteen years old.

Nonetheless, as Alice Sanford’s article in the Vassar Miscellany (June 1915) explains, the success of Daddy-Long-Legs created many opportunities for actual orphans:

“One hundred orphan children have since been placed in families by the Society of the National Sons and Daughters of the Golden West. Miss Webster has been consulted repeatedly by prominent social workers to suggest improvements in children’s institutional homes, besides being invited to become a Director in many of them.”

Whether true or not, the author having been described as an orphan would have made Judy’s story about life at the John Grier Home and Fergussen College more credible. And decades after the author’s death, Vassar praised Daddy-Long-Legs as “a moving revelation of child-life in an orphanage, timeless in its humor, justice, and lovable make-believe.”

The book’s social welfare message “that under-privileged children, if given a chance, are capable of succeeding in life and of enjoying its beauty” is simple but powerful. (September 1936, Vassar Miscellany)

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Jean Webster

. . . . . . . . .

Girls-in-progress: Selfhood

I also related to the work-in-progress nature of young Jerusha, who changed her name to “Judy” when she went to Fergussen Hall (the author herself changed from “Alice” to “Jean” when she went to college), echoing Anne imagining herself into becoming “Cordelia” in L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1908).

I was waiting for someone to see the real me, like Judy’s benefactor saw her: “He believes that you have originality, and he is planning to educate you to become a writer.”

In the story, “Jerusha” was said to be a name from a tombstone and a telephone book. In real life, Jean Webster’s friend Ethelyn McKinney had a grandmother named Jerusha, and Jean’s connection to the McKinney family intensified when she married Ethelyn’s brother in 1915 (though nobody claimed the grandmother’s name was an inspiration).

Eventually, Judy’s story would succeed not only on the printed page but on the Broadway stage and multiple Hollywood films. Webster herself adapted the work for theatre and Alice Sanford shares this evidence of the author’s commitment to its success:

“It is a fact that on the opening night of the play in February at Atlantic City, Mr. [Henry] Miller was very nervous and dubious, and said to Miss Webster that he would sell out the house for twenty dollars. She, however, was confident, and predicted a success.”

Boarding schools

I preferred Enid Blyton-style school stories to literary alternatives; Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre bored me after Jane left Lowood and only finished reading it decades later. When Sara Crewe was in classes with Miss Minchin in A Little Princess, life was fine, but her fortunes soon took a turn.

Judy’s life at Fergussen Hall was more bookish than the Naughtiest Girl, St. Clare’s, and Malory Towers stories. Although lacking the privileges of her well-to-do classmates, Judy must catch up scholastically and socially:

“The trouble with college is that you are expected to know such a lot of things you’ve never learned. It’s very embarrassing at times.”

I preferred the stories where children connected with teachers who recognized their talents, and even though I was less fond of books about boys (unless they were one of the Three Investigators or the love interest in a Beverly Cleary romance), a story like Irene Hunt’s The Lottery Rose squeaked past my anti-boy bias because of the boarding-school setting.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Judy includes specifics about her classes and her independent work, which held its own appeal. Jean Webster’s homage to her beloved Vassar College is most immediately recognizable in When Patty Went to College (1903) and Just Patty (1911). But a 1912 review in the Vassar Miscellany by Gabrielle Elliot situates Daddy-Long-Legs there too:

“Perhaps the earmarks are not quite so plain, but when we find the heroine trying to make a tower room livable, taking the ‘entertaining’ Benvenuto Cellini’s life in chunks and writing ‘humorous’ songs for a Glee Club concert our suspicions are more or less confirmed.”

From the perspective of a fellow Vassar graduate, the school setting was one of the novel’s most appealing elements:

“The description of how ‘Judy’ nightly fortified herself behind an engaged sign and acquired in gulps the knowledge which everyone is assumed to have is extremely amusing. Perhaps the most genuine part of the book comes in one or two perceptive touches of the everyday life at college.”

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

Works-in-progress: Writing

Although I warmed to the details of Judy’s coursework—which wars she was studying and which verbs she was conjugating — her growing identity as a writer thrilled me more. In concert with the sense that I — and only I — was the reader of this story, other than the bookish girl who made it.

“I look forward all day to evening, and then I put an ‘engaged’ on the door and get into my nice red bathrobe and furry slippers and pile all the cushions behind me on the couch, and light the brass student lamp at my elbow, and read and read and read.

One book isn’t enough. I have four going at once. Just now, they’re Tennyson’s poems and Vanity Fair and Kipling’s Plain Tales and – don’t laugh – Little Women. I find that I am the only girl in college who wasn’t brought up on Little Women. I haven’t told anybody though (that would stamp me as queer).”

Judy’s letters read more like a diary because her benefactor never writes back. Throughout the book, she is reading, mostly for school but sometimes for pleasure: “Excuse me for filling my letters so full of [Robert Louis] Stevenson; my mind is very much engaged with him at present.”

And, eventually, she is writing as much as she is reading, particularly during the summer holidays: “College opens in two weeks and I shall be glad to begin work again. I have worked quite a lot this summer though—six short stories and seven poems. Those I sent to the magazines all came back with the most courteous promptitude. But I don’t mind.”

From the start, it felt like she was writing both to me and about me. Books like Lois Lowry’s Anastasia Krupnik (1979) and Norma Fox Mazer’s I, Trissy (1971) had revealed the power of intimacy in handwritten pages. Judy’s story unfolded decades earlier, but her hand-drawn, near-stick figures were as disproportioned as my own doodles, and her bookishness was recognizable and her friendships were enviable.

Spiders and titles

Judy addresses her letters to Daddy-Long-Legs because of a silhouette she has glimpsed, that of a very tall man (her benefactor), but the title had another genesis, which Alice Sanford describes:

“Five or six summers ago Miss Webster was visiting at the home of her publisher, and as they all were sitting on the porch, a daddy-long-legs dropped into her lap. ‘Oh, a daddy-long-legs,’ she exclaimed — ‘what a capital title for a book!’ and the publisher said upon her leaving, ‘Don’t forget to write the book.’”

Jean Webster didn’t take it seriously, but her publisher did:

“After receiving a mock-up ‘with the picture of a daddy-long-legs emblazoned upon it’ Jean Webster got to work. Over the next couple of years, she noodled the idea and conceived of a ‘little orphan asylum girl, Judy, who finally goes to college through the munificence of the aristocratic Jervis Pendleton, self-styled misogynist.’”

. . . . . . . . . .

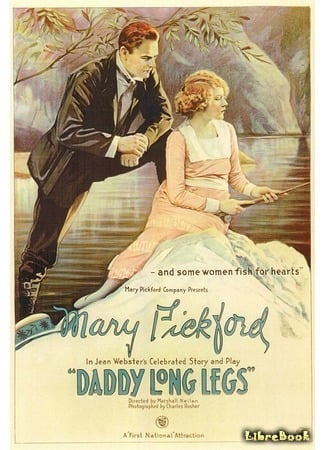

The first film version, 1919

. . . . . . . . . .

Enduring, rereading

Jervis is a shadowy figure in the novel, but in later adaptations, the relationship between him and Judy is more prominent. More than a decade after I first read the book, I finally saw a film that I recognized as being adapted from it.

In between, I had seen Shirley Temple’s Curly Top (1935) but I didn’t recognize it as the same story. The first film, made by Mary Pickford in 1919, wasn’t available (likely for the best, as the orphanage scenes probably would have given me nightmares), although Canadian students studied Mary Pickford in school as dutifully as Judy studied algebra and physiology.

Rewatching the 1955 film Daddy-Long-Legs recently, I was struck by how much of it was about Jervis Pendleton, which is perhaps best explained by the fact that Fred Astaire was cast in the role, opposite Leslie Caron.

Rumor has it that he was surprised to be cast opposite a ballerina, quickly announcing: “Kid, you’re going to have to do what I do, because I sure don’t do what you do.” As Judy in the film, Leslie Caron does what Fred Astaire as Jervis does: dancing makes for better showmanship than reading or writing.

Bolstering Daddy-Long-Legs’ popularity has been a series of stage and screen productions: films in 1990 in Japan, and in 2005 in Korea; on-stage as Love from Judy in 1952 in England, as a two-person musical in California in 2009, and stage production in New York City in 2015.

But it’s the novel that holds the most appeal for me. Other readers of classic girls’ stories often count it among their favorites too, both in North America and in England (where many of Jean Webster’s novels were published, often a year or two after their American debut).

In 2005, Amanda Craig, nominated more than once for the International Women’s Fiction Prize, included it in a list of her favorite teen romances in the London Times, describing it like this: “Sweet novel made up of an adopted girl’s letters to her daddy.”

She’s not adopted and he’s not her daddy, yet this statement is no more inaccurate than the biographical note at the back of the novel that identifies Jean Webster as an orphan. The point is that Judy doesn’t feel like she belongs anywhere and her Daddy-Long-Legs helps her believe that she does. It’s a human yearning to connect: it’s what we look for in a story and it’s why I return to Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More about Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster

- Read full text on Project Gutenberg

- Listen on Librivox

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Jean Webster on the Vassar Encyclopedia

Leave a Reply