Playing Town: Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy

By Marcie McCauley | On May 9, 2019 | Updated June 30, 2023 | Comments (5)

Marcie McCauley reflects on revisiting Harriet the Spy, the 1964 classic by Louise Fitzhugh, and how the story continues to resonate and inspire her as a working writer.

See, first you take off your coat and hang it on the back of a library chair, use it to mark a comfortable seat as your place to return to with a stack of books. Then you fetch the ones you remember most fondly. You can’t have too many at one time or the librarians are annoyed. I usually have ten.*

This is how you play Library, based on Harriet’s technique for playing Town as she explains it to her friend, Sport.

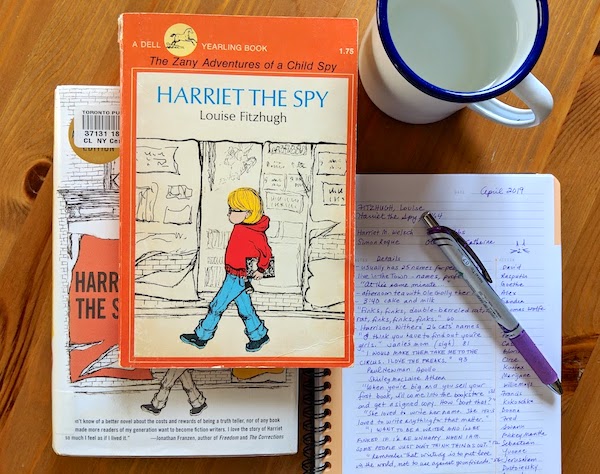

The way Harriet describes the rules in Harriet the Spy is as familiar to me as the smell of this 1964 hardcover. “See, first you make up the name of the town. Then you write down the names of all the people who live in it. You can’t have too many at one time or it gets too hard. I usually have twenty-five.”

Even though it is not a copy which I have read before, this well-worn library copy has absorbed the quintessential smell I remember from spending time with Harriet when I was a girl. (I borrowed a copy from my friend sometimes but more often from the public library.)

Learning the rules of Town

Back then, I was learning the rules of Town along with Sport. Now I recognize that Louise Fitzhugh is talking as much about the game of Storytelling as any other pastime.

Harriet begins with the men’s names, the wives’ names, the children’s names, their professions and then the fun begins: the stories about the residents.

“Ole Golly told me if I was going to be a writer I better write down everything, so I’m a spy that writes down everything,” Harriet tells the Cook.

Harriet’s family has a cook and she also occasionally eats at the luncheonette where she orders chocolate egg creams. Her house, on East Eighty-seventh Street in Manhattan, has a courtyard. And Harriet has a nurse named Ole Golly.

This was nothing like my childhood of low-rent apartments, processed noodles and fast-food for special occasions, and a library instead of a babysitter.

But Harriet also has a notebook. And I had notebooks. Four-packs bought at the hardware store every September and palm-sized coil notebooks with photographs of kittens on their covers: the former to be rationed and the latter to remain meticulously preserved.

Harriet wrote things down “because [she’s] seen them and [she wants] to remember them” when she had her notebook with her and she “fairly itched to take notes” even when she could not, and every night after she goes to bed, she hides under the covers where she reads “happily until Ole Golly came in and took the flashlight away.”

. . . . . . . . . .

You might also enjoy: Quotes from Harriet the Spy

. . . . . . . . . .

Ole Golly: A vital force

Ole Golly is a vital force in Harriet’s life. She quotes writers like Henry James on the practice of afternoon tea and Wordsworth on the “inward eye which is the bliss of solitude”, writers like Cowper and Emerson, and she advises Harriet on a writer’s eye and a writer’s responsibility.

Sometimes, however, Harriet wishes Ole Golly “would just shut up.” This is Harriet all over. Because only Ole Golly understands that Harriet needs her “pen flying over the pages, of her thoughts, finally free to move, flowing out.”

Without Ole Golly, Harriet’s life would be a world filled with judgements like those of her friend Janie’s mother, who warns: “I think you girls have something to learn. I think you have to find out you’re girls.”

Harriet had Ole Golly and nine-year-old-me had Harriet, who was eleven years old and donned a pair of eyeglasses without lenses because she wanted to look smart. (I wore mine only because my teacher called home to say that I had been keeping them in my desk.)

I wrote things in my notebook. I read under the covers. I didn’t wear the kind of clothes that young girls were expected to wear. And, after I met Harriet, I realized that made me a spy. And knowing Harriet made all of that okay, for me and for other writers.

Tributes for Harriet’s 50th anniversary edition

In recalling her experience of Harriet in a set of tributes collected in the book’s 50th anniversary edition (Delacorte Books, 2014), Judy Blume observes: “She had secrets; I had secrets. She was curious; I was curious.”

Gregory Maguire marvels: “She was trying to find out from lives what life itself was about.” And Rebecca Stead concludes “there are some kinds of loneliness we must learn to live with”.

It’s true that much of the story revolves around Harriet’s secrecy and solitude and what she observes about other people’s secrets, as she follows her regular route through the neighborhood. So it’s fair to say that much of the story unfolds in Harriet’s head: “She sat there thinking, feeling very calm, happy, and immensely pleased with her own mind.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Friendships with Janie and Sport

Not all of Harriet’s time is spent spying, note-taking and being immensely pleased, however: the book begins and ends with Harriet’s friends. Sport and Janie are key figures, whom Harriet has the opportunity to observe closely and, in turn, their behavior leads Harriet to see herself in new (sometimes startling) ways.

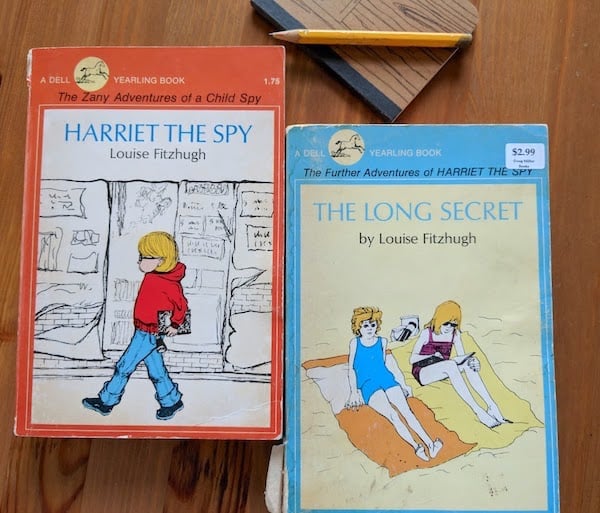

Sport has his own self-titled book, published in 1979, five years after Louise Fitzhugh’s death, and Janie also appears in The Long Secret, which was published in 1965 (although Beth Ellen is at the heart of that story).

Sport lives with his father, a novelist who works all night in an apartment that smells like old laundry (which also contributes to Harriet’s understanding of a writer’s life). Janie lives with two parents in a renovated brownstone where she has a chemistry set and explosive aspirations.

These friendships and Harriet’s relationships with other neighborhood and school friends are significant, and individual children are sketched in detail (sometimes literally, as Louise Fitzhugh’s illustrations are scattered throughout the book), but the primary relationship in Harriet’s life is with her series of notebooks.

When readers meet her, she is writing in her fifteenth notebook, and when that relationship is fractured, Harriet is broken too. “She grabbed up the pen and felt the mercy of her thoughts coming quickly, zooming through her head out the pen onto the paper. What a relief, she thought to herself; for a moment I thought I had dried up.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Revisiting Harriet the Spy as an adult

Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s novel as an adult, I’m no longer convinced that Harriet and I would have been friends off the page. We would never have summered together in Water Mill, Long Island. We would never have had a sleepover on a Saturday night while her parents attended a white-tie-and-tails party.

On the page, however, we could be best friends. Like me, Harriet is “just so about a lot of things” and the only kind of sandwich in her world is a tomato sandwich. When she “didn’t have a notebook it was hard for her to think” and she gets a “funny hole somewhere above her stomach” when she loses the person in her life who knows her best.

And perhaps most importantly, when she plays Town, she plays so hard that even her friends are like characters in her life – impediments to and inspirations for – doing the work of telling stories.

In that sense, Harriet and I have lived in the same Town from the moment we met, and, even still, that Town is a place I visit every day.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, whose “spy reports” have been published online and printed in literary journals in North America and Europe. She spies and writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. You can also find her online at Marcie McCauley and on Twitter @buriedinprint.

Splendid!!! Must re-read!

Bless you. I have never read Harriet the Spy, but have always known of it. I can’t imagine it being banned. Thank you for this insight. I will surely read it now. What an amazing book to help children understand their lives, and that it is ok to observe and record those observations, even into stories.

Thank you, Diane. Sometimes children’s books have such amazing insights. I hope you’ll enjoy it!

Thank you. I will return to “children’s” books for insight.

Thank you, Rob. I’m due for a re-read, as it was a favorite of my childhood!