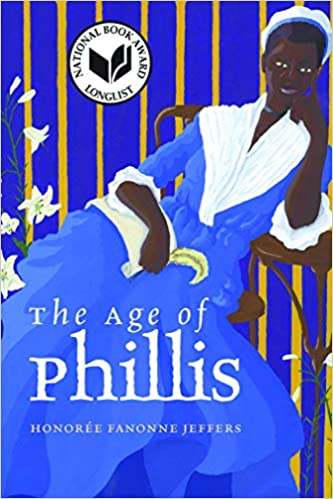

The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers: A review

By Lynne Weiss | On May 2, 2021 | Updated March 14, 2025 | Comments (0)

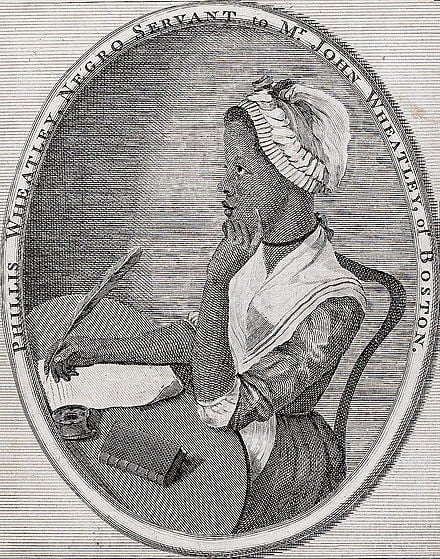

The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers illuminates the life and significance of Phillis Wheatley Peters, the enslaved African American whose 1773 book of poetry, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, challenged prevailing assumptions about the intellectual and moral abilities of Africans and women.

In The Age of Phillis (Wesleyan University Press, 2020), which won the 2021 NAACP Image Award for “Outstanding Literary Work—Poetry” and was long-listed for the National Book Award, Jeffers portrays the life of the poet both before she was taken from her home in West Africa and throughout her lifetime in the United States, first enslaved and later free.

I became aware of the book by attending a virtual reading and can attest that Jeffers’s reading style is dynamic and worth searching out in audio and video recordings on the internet.

Jeffers, recipient of the 2018 Harper Lee Award for Literary Distinction (a lifetime achievement award), presents not only Wheatley, but many others of her era, enslaved and free, through one hundred poems that draw on primary sources to provide insight not only into the circumstances of Wheatley’s life, but into the people and conditions that condoned the horrors of slavery.

Jeffers portrays the ways that these conditions affected Phillis even when she is not directly mentioned. The poem “Catalog: Water,” describes the 1781 voyage of the slave ship Zong, in which well over one hundred (estimates range between 130 and 180) living enslaved people were thrown overboard to drown, in verses that appear arranged on the page to evoke a sailing ship’s tacking against the wind.

Jeffers begins:

I know I’ll try your patience,

As I have for several years:

When I talk of slavery,

And ends by saying

Don’t you know that

Drowned folks will rise

To croon signs to me?

And anyway, I didn’t tell

This story to please you.

I built this altar for them.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Phillis Wheatley

10 Poems by Phillis Wheatley

James Weldon Johnson’s Analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s Poetry

. . . . . . . . . . .

An imagined biography based on research

Jeffers employs a variety of poetic forms to present a largely imagined biography of Wheatley, drawing on information she gleans from existing sources to postulate the area of her birth (likely the West African region of Senegambia), her religion (likely Muslim), her life with the Wheatleys (who purchased her from a Boston slave market), her friendship with Obour Tanner (a woman enslaved in nearby Rhode Island), her travel to London following the publication of her book, and her courtship and marriage to John Peters.

I especially like Jeffers’s use, at times, of different typefaces to indicate a double consciousness on the part of Wheatley and others—a consciousness of her African heritage as well as of her circumstances in colonial Boston. In essence, Jeffers conveys the necessity of code-switching. “Lost Letter #14: John Peters, Boston, to Phillis Wheatley, Boston” briefly excerpted here, offers one example:

… Miss Wheatley,

will you take my favor to heart? If you will not

cherish me, at least, will you not discard?

[…here is a black

man in front of you I am not afraid to love you

in the old african ways here is someone your father

would accept woman I am asking for your hand]

Wheatley’s contemporaries

Other poems portray the struggles of Phillis’s contemporaries—including those of Elizabeth Freeman, who sued for her freedom; of Ona Judge, who escaped enslavement in the home of George and Martha Washington; and of Belinda Sutton, who won a pension from the state of Massachusetts for the years in which she was enslaved.

We learn of Black men who fought for American independence and of those who won freedom in Canada by fighting for the British.

In one particularly striking poem, Jeffers portrays George Washington’s consternation over how to respond to a poem and a letter he received from Phillis:

Her letter trembles in my hand, dances

with confusion, swaying past the stars—

… and makes it clear that Phillis is a challenge to that other age, the term often used to describe the era of the American Revolution—the Enlightenment, or the Age of Reason, and its failure to dismantle slavery:

Her quill and life defy my age’s Reason.

The word Reason can be read in different ways in this line: it can suggest common sense and might at the same time refer to the rationale for enslavement—white supremacy. Either way, the poem is a brilliant response to one of Wheatley’s most famous poems — “To His Excellency General Washington.”

I’ve read this oft-anthologized poem many times. When I was younger, the old-fashioned language bored me. Later, it made me uncomfortable to read an enslaved woman praising a white male slaveowner in the elevated language of heroic couplets—but Jeffers’s depiction of Washington’s discomfiture on receiving Wheatley’s poem transforms it from an act of obeisance to one of self-assertion.

A multiplicity of meanings

What I appreciated most about Jeffers’s book was the multiplicity of meanings I found in the title. Most obviously, “the age of Phillis” refers to the era in which Phillis lived and wrote. But the title poem, one of the most moving in the book, begins by asking:

How old was the child when she first laughed/in her master’s kitchen?

and ends by asking

And what was the age

of Phillis when she stopped turning East,

thinking of water in faithful bowls

of her parents,

of love only ending in death?

There is no such age. There never will be

though a sister’s mouth might tell you lies.

But ultimately, Jeffers implies that the age of Phillis is still with us by presenting many poems in the form of blues and by drawing on the work of the Black poets and artists for whom Wheatley opened the way.

Anyone who picks up this book will benefit from the notes on the poems, as Jeffers explains in them the connections of various poems to the work of those such as June Jordan, Romare Bearden, Langston Hughes, Robert Hayden, Lucille Clifton, Elizabeth Alexander, Audre Lorde, Rita Dove, Nikki Giovanni, and Paul Lawrence Dunbar.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Contradictions and challenges

Finally, this remarkable book ends with a 20-page essay titled “Looking for Miss Phillis,” in which Jeffers describes her fifteen-year search for historical documentation into the life of Wheatley and those she knew.

What she finds leads her to question the reliability of the author of the most frequently cited source on Wheatley, Margaretta Matilda Odell, a white woman who identified herself as the relative of Susanna Wheatley, Phillis’s owner. Odell wrote about the poet fifty years after Phillis’s death.

While Odell offers Phillis’s achievements as an argument against slavery, Jeffers points out that her depiction of John Peters as abusive and untrustworthy is contradicted by the historical record.

Jeffers speculates that Odell might have perceived Peters, who tried and failed in several enterprises, including law, commerce, and real estate, as an “uppity” man, but in the present day, one can’t help but wonder about the role of racism in his failures.

While Odell claims that Peters abandoned Phillis, Jeffers finds evidence that the man was in debtors’ prison, likely the result of his business failures. Thus Phillis, despite her genius, faced the same systemic financial and legal barriers that hinder many African American people today.

The combination of the poems, the notes on the poems, and the essay add power to this unusual book and pave the way for a reinterpretation of Wheatley’s poems that acknowledge her true circumstances before, during, and after her enslavement.

What might appear to be a collection of poems inspired by Wheatley and her time demands to be read as a unity, much like a novel or biography.

Phillis Wheatley has been called a genius for her mastery of traditional poetic forms despite her arrival in Boston with not a word of English or any level of literacy. Y

et Jeffers’s depiction asks us to attribute yet another form of genius to Wheatley — her ability to master the code-switching that must have been essential to her survival and her poetic and public achievements. Jeffers has recently published her first novel, The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois. I suspect I am only one of many who cannot wait to read it!

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, she has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

Leave a Reply