James Weldon Johnson’s Analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s Poetry

By Taylor Jasmine | On November 2, 2024 | Updated November 14, 2024 | Comments (0)

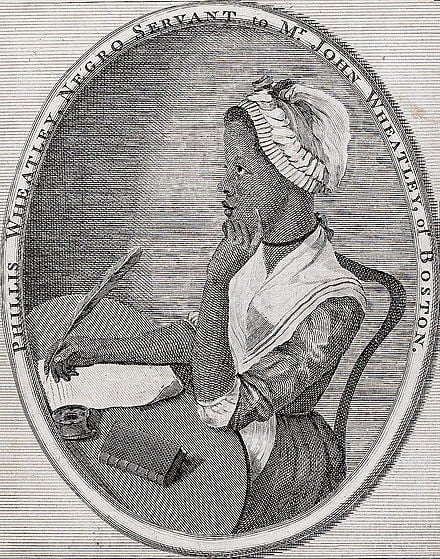

Presented here is an analysis by James Weldon Johnson of Phillis Wheatley’s poetry. She was one of the first women to be published in colonial America, and the first person in the U.S. to have a book of poetry published while enslaved.

James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) was a writer, educator, poet, diplomat, and civil rights activist. He helmed the NAACP from 1920 to 1930. He was a significant figure in the Harlem Renaissance movement, or as it was then called, The New Negro movement.

The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), chosen and edited by Johnson, was one of a handful of significant anthologies of Black literature to be published in the 1920s. The segment following, in which he provides and analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s poetry, is a portion of the Johnson’s Preface to this collection. It is in the public domain.

Phillis Wheatley’s Poetry: An Analysis by James Weldon Johnson

In 1761 a slave ship landed a cargo of slaves in Boston. Among them was a little girl seven or eight years of age. She attracted the attention of John Wheatley, a wealthy gentleman of Boston, who purchased her as a servant for his wife.

Mrs. Wheatley was a benevolent woman. She noticed the girl’s quick mind and determined to give her opportunity for its development. Twelve years later Phillis published a volume of poems. The book was brought out in London, where Phillis was for several months an object of great curiosity and attention.

Phillis Wheatley has never been given her rightful place in American literature. By some sort of conspiracy she is kept out of most of the books, especially the text-books on literature used in the schools.

Of course, she is not a great American poet—and in her day there were no great American poets—but she is an important American poet. Her importance, if for no other reason, rests on the fact that, save one, she is the first in order of time of all the women poets of America. And she is among the first of all American poets to issue a volume.

It seems strange that the books generally give space to a mention of Urian Oakes, President of Harvard College, and to quotations from the crude and lengthy elegy which he published in 1667; and print examples from the execrable versified version of the Psalms made by the New England divines, and yet deny a place to Phillis Wheatley …

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Phillis Wheatley

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne Bradstreet preceded Phillis Wheatley by a little over twenty years. She published her volume of poems, “The Tenth Muse,” in 1750. Let us strike a comparison between the two.

Anne Bradstreet was a wealthy, cultivated Puritan girl, the daughter of Thomas Dudley, Governor of Bay Colony. Phillis, as we know, was a Negro slave girl born in Africa. Let us take them both at their best and in the same vein. The following stanza is from Anne’s poem entitled “Contemplation”:

While musing thus with contemplation fed,

And thousand fancies buzzing in my brain,

The sweet tongued Philomel percht o’er my head,

And chanted forth a most melodious strain,

Which rapt me so with wonder and delight,

I judged my hearing better than my sight,

And wisht me wings with her awhile to take my flight.

And the following is from Phillis’s poem entitled “Imagination”:

Imagination! who can sing thy force?

Or who describe the swiftness of thy course?

Soaring through air to find the bright abode,

The empyreal palace of the thundering God,

We on thy pinions can surpass the wind,

And leave the rolling universe behind,

From star to star the mental optics rove,

Measure the skies, and range the realms above,

There in one view we grasp the mighty whole,

Or with new worlds amaze the unbounded soul.

We do not think the Black woman suffers much by comparison with the white. Thomas Jefferson said of Phillis: “Religion has produced a Phillis Wheatley, but it could not produce a poet; her poems are beneath contempt.”

It is quite likely that Jefferson’s criticism was directed more against religion than against Phillis’ poetry. On the other hand, General George Washington wrote her with his own hand a letter in which he thanked her for a poem which she had dedicated to him. He, later, received her with marked courtesy at his camp at Cambridge.

It appears certain that Phillis was the first person to apply to George Washington the phrase, “First in peace.” The phrase occurs in her poem addressed to “His Excellency, General George Washington,” written in 1775.

The encomium, “First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen” was originally used in the resolutions presented to Congress on the death of Washington, December, 1799.

Phillis Wheatley’s poetry is the poetry of the Eighteenth Century. She wrote when Pope and Gray were supreme; it is easy to see that Pope was her model. Had she come under the influence of Wordsworth, Byron or Keats or Shelley, she would have done greater work.

As it is, her work must not be judged by the work and standards of a later day, but by the work and standards of her own day and her own contemporaries. By this method of criticism she stands out as one of the important characters in the making of American literature, without any allowances for her sex or her antecedents.

According to A Bibliographical Checklist of American Negro Poetry, compiled by Mr. Arthur A. Schomburg, more than one hundred Negroes in the United States have published volumes of poetry ranging in size from pamphlets to books of from one hundred to three hundred pages. About thirty of these writers fill in the gap between Phillis Wheatley and Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Just here it is of interest to note that a Negro wrote and published a poem before Phillis Wheatley arrived in this country from Africa. He was Jupiter Hammon, a slave belonging to a Mr. Lloyd of Queens-Village, Long Island.

In 1760 Hammon published a poem, eighty-eight lines in length, entitled “An Evening Thought, Salvation by Christ, with Penettential Cries.”

In 1788 he published “An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, Ethiopian Poetess in Boston, who came from Africa at eight years of age, and soon became acquainted with the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” These two poems do not include all that Hammon wrote.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

The poets between Phillis Wheatley and [Paul Laurence] Dunbar must be considered more in the light of what they attempted than of what they accomplished. Many of them showed marked talent, but barely a half dozen of them demonstrated even mediocre mastery of technique in the use of poetic material and forms …

Only very seldom does Phillis Wheatley sound a native note. Four times in single lines she refers to herself as “Afric’s muse.” In a poem of admonition addressed to the students at the “University of Cambridge in New England” she refers to herself as follows:

Ye blooming plants of human race divine,

An Ethiop tells you ’tis your greatest foe.

But one looks in vain for some outburst or even complaint against the bondage of her people, for some agonizing cry about her native land. In two poems she refers definitely to Africa as her home, but in each instance there seems to be under the sentiment of the lines a feeling of almost smug contentment at her own escape therefrom. In the poem, “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” she says:

Twas mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God and there’s a Saviour too;

Once I redemption neither sought or knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

‘Their color is a diabolic dye.’

Remember, Christians, Negroes black as Cain,

May be refined, and join th’ angelic train.

In the poem addressed to the Earl of Dartmouth, she speaks of freedom and makes a reference to the parents from whom she was taken as a child, a reference which cannot but strike the reader as rather unimpassioned:

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood;

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat;

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labor in my parents’ breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d;

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

The bulk of Phillis Wheatley’s work consists of poems addressed to people of prominence. Her book was dedicated to the Countess of Huntington, at whose house she spent the greater part of her time while in England. On his repeal of the Stamp Act, she wrote a poem to King George III, whom she saw later; another poem she wrote to the Earl of Dartmouth, whom she knew.

A number of her verses were addressed to other persons of distinction. Indeed, it is apparent that Phillis was far from being a democrat. She was far from being a democrat not only in her social ideas but also in her political ideas; unless a religious meaning is given to the closing lines of her ode to General Washington, she was a decided royalist:

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine

With gold unfading, Washington! be thine.

Nevertheless, she was an ardent patriot. Her ode to General Washington (1775), her spirited poem, “On Major General Lee” (1776) and her poem, “Liberty and Peace,” written in celebration of the close of the war, reveal not only strong patriotic feeling but an understanding of the issues at stake.

In her poem, “On Major General Lee,” she makes her hero reply thus to the taunts of the British commander into whose hands he has been delivered through treachery:

O arrogance of tongue!

And wild ambition, ever prone to wrong!

Believ’st thou, chief, that armies such as thine

Can stretch in dust that heaven-defended line?

In vain allies may swarm from distant lands,

And demons aid in formidable bands,

Great as thou art, thou shun’st the field of fame,

Disgrace to Britain and the British name!

When offer’d combat by the noble foe,

(Foe to misrule) why did the sword forego

The easy conquest of the rebel-land?

Perhaps TOO easy for thy martial hand.

What various causes to the field invite!

For plunder YOU, and we for freedom fight,

Her cause divine with generous ardor fires,

And every bosom glows as she inspires!

Already thousands of your troops have fled

To the drear mansions of the silent dead:

Columbia, too, beholds with streaming eyes

Her heroes fall—’tis freedom’s sacrifice!

So wills the power who with convulsive storms

Shakes impious realms, and nature’s face deforms;

Yet those brave troops, innum’rous as the sands,

One soul inspires, one General Chief commands;

Find in your train of boasted heroes, one

To match the praise of Godlike Washington.

Thrice happy Chief in whom the virtues join,

And heaven taught prudence speaks the man divine.

What Phillis Wheatley failed to achieve is due in no small degree to her education and environment. Her mind was steeped in the classics; her verses are filled with classical and mythological allusions. She knew Ovid thoroughly and was familiar with other Latin authors. She must have known Alexander Pope by heart.

And, too, she was reared and sheltered in a wealthy and cultured family—a wealthy and cultured Boston family; she never had the opportunity to learn life; she never found out her own true relation to life and to her surroundings. And it should not be forgotten that she was only about thirty years old when she died.

The impulsion or the compulsion that might have driven her genius off the worn paths, out on a journey of exploration, Phillis Wheatley never received. But, whatever her limitations, she merits more than America has accorded her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Leave a Reply