Phillis Wheatley, First African American Poet

By Nava Atlas | On March 13, 2018 | Updated November 2, 2024 | Comments (0)

Phillis Wheatley (ca 1753 – December 5, 1784), born in Senegal/Gambia, Africa, was one of the first women to be published in colonial America. She was also the first person in the U.S. to have a book of poetry published while enslaved.

Phillis was kidnapped as part of the slave trade as a young child and brought to North America, where she arrived on July 11, 1761. She arrived on a schooner, The Phillis, undoubtedly the source of her name.

Later, she was described as “a slender, frail female child, supposed to have been about seven years old at the time, from the circumstances of shedding her front teeth.”

John Wheatley, a prosperous tailor and merchant of Boston bought the little girl from the slave market to be a personal servant to his wife, Susanna. As was customary at the time, she was given the surname of the family to whom she was in bondage.

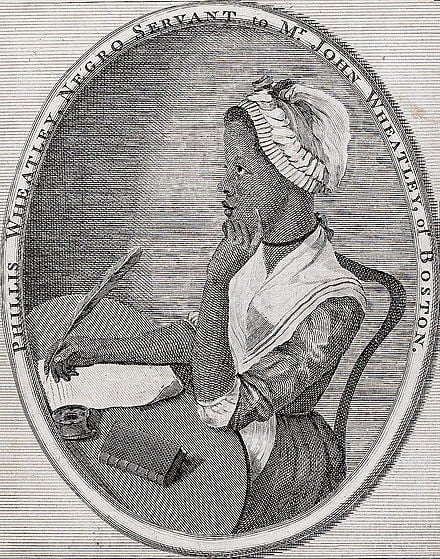

The iconic portrait of Phillis Wheatley shown in this post is an engraving attributed to Scipio Moorhead, an enslaved African American in Boston who was a talented artist. It’s the only existent picture of her likeness.

Early promise and keen intellect

It was soon apparent that Phillis had remarkable intellectual abilities, and under Susanna’s guidance, was educated along with Wheatley’s daughters.

Within a year and a half, she was able to read the Bible and wrote English fluently. This was quite a rarity at a time when enslaved people were actively discouraged from learning to read and write. In most cases, it was forbidden altogether.

Not only was Phillis encouraged in her literary talents, she also learned Greek, Latin, ancient history and theology. She was able to translate a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, inspiring a poem that would later be published.

First verses and a poetry collection

Having spoken no English when she arrived in 1761, Phillis began writing verse in 1765 as she had quickly mastered the English language. Under the influence of the Wheatley’s Puritan household, Phillis had become a devout Christian. This, along with her education in classic languages and literature, had a profound impact on the subject matter and structure of her poetry.

When she was between 13 and 14 years old, Phillis’s first poem, submitted by Susanna Wheatley on her behalf, was published in The Newport Mercury. Further publication of her poems spread the word of her talent in the colonies.

. . . . . . . . . .

This portrait of Phillis Wheatley was the frontispiece of

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773)

. . . . . . . . . .

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., wrote in The Trials of Phillis Wheatley (2003): “In 1770, when she was about 17, she immortalized the Boston Massacre in her poem, ‘On the Affray in King Street, on the Evening of the 5th of March, 1770 …” An elegy to a popular religious figure, the Reverend George Whitefield, augmented the fledgling poet’s growing fame in the colonies. Further, writes Gates:

“Delighted with her slave’s dazzling abilities and her growing fame, Susanna Wheatley set out to have Phillis’s work collected and published as a book. Advertised in the Tory paper, the Boston Censor [in 1772], was a list of the titles of the twenty-eight poems that would make up the book if enough subscribers — perhaps 300 — could be found to underwrite the cost of the publication.

But the necessary number of subscribers could not be found because not enough Bostonians could believe that an African slave possessed the requisite degree of reason and wit to write a poem by herself.”

The Wheatley family was accused of fraud in claiming that Phillis had produced such fine poetry, and were even subject to an investigation. Though the verdict was in their favor, it didn’t help Phillis’s prospects. Printing was still a fledgling industry in the colonies, unlike the flourishing publishing business in England. Undaunted, the family set their sights across the Atlantic.

. . . . . . . . .

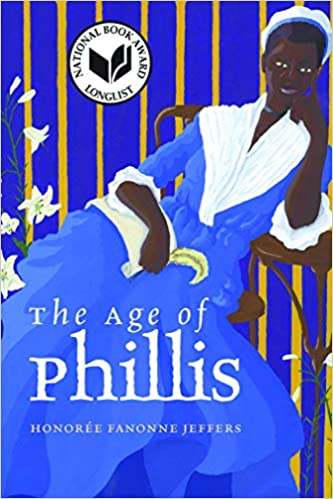

The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fannone Jeffers: A Review

. . . . . . . . .

Publication in England

Selina Hastings, the English Countess of Huntingdon, was known for supporting writers of African origins and agreed to finance the publication of Phillis’s collection of poetry in London. It was the Countess who suggested that a portrait of Phillis as the book’s frontispiece would “contribute greatly to the Sale of the Book”— fueling the curiosity of an enslaved female as poet.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the intellectual and moral capacity of enslaved Africans was being argued, and Phillis’s book would test prevailing notions. Her very personhood was up for debate. She and the Wheatleys were aware that her book might prove controversial, and knowingly took the risk.

In the spring of 1773, the Wheatley’s son Nathaniel set sail for England on business. Phillis, then nineteen, traveled with him. The plan was for her to be present when the book rolled off the press, then to stay and promote it. While awaiting publication, she had a wonderful time touring London, and was even introduced to some of England’s nobility.

Shortly before the big date, Phillis and Nathaniel received word that Susanna’s health was failing. Distraught, Phillis decided to sail back to the colonies. It was an extremely unusual situation for an enslaved person, but Phillis claimed to feel more like a daughter to Susanna.

The fall of 1773 was both bitter and sweet. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston, in New England was published as planned, and was quite well received in England.

However, Susanna died, leaving Phillis devastated. And though John freed her soon after his wife’s death, she remained with him and his daughter Mary until they too died a few years later.

Admired by Washington

In late 1775, Phillis sent verses to General George Washington. In response, he wrote: “I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me in the elegant lines you inclosed; and, however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyric, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your poetical talents …”

Here is the first stanza of the poem:

His Excellency General Washington

Celestial choir! enthron’d in realms of light,

Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.

While freedom’s cause her anxious breast alarms,

She flashes dreadful in refulgent arms.

See mother earth her offspring’s fate bemoan,

And nations gaze at scenes before unknown!

See the bright beams of heaven’s revolving light

Involved in sorrows and the veil of night!

The verses she shared with the soon-to-be first president of the U.S. were published in Pennsylvania Magazine in April 1776. Thomas Jefferson was also a reader of her poetry, writing that her verses were “beneath criticism.”

Yet, he remained somewhat of a skeptic, or perhaps more accurately a cynic. This is perhaps not surprising given his complicated legacy when it came to slavery. Henry Louis Gates elaborates:

“Yes, he concludes, she may very well have written these works, but they are derivative, imitative, devoid of that marriage of reason and transport that is, in his view, the peculiar oestrum of the poet.

By shifting the terms of authenticity—from the very possibility of her authorship to the quality of her authorship—Jefferson indicted her for a failure of a higher form of authenticity … and the complex rhetoric of authenticity would have a long, long afterlife.”

. . . . . . . . . .

James Weldon Johnson’s Analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s Poetry

. . . . . . . . . .

Unfortunate circumstances after freedom

When the Wheatley family was broken up by death in the 1770s, Phillis was emancipated. Still, she was devastated by the deaths of Susanna and John.

Phillis, still a young woman, was now alone in the world (Nathaniel had returned to England to marry). The social constraints of the time made it nearly impossible for a young former enslave woman to fend for herself. Poems on Various Subjects (finally published in Boston) went through many editions in her lifetime and beyond; evidently, someone other than Phillis was profiting from the sales.

In 1778 she met and married John Peters, a free black man, but the union was marred by their impoverished circumstances. During the Revolution, the couple resided in Wilmington, Delaware, then returned to Boston, where they lived in abject poverty.

Phillis was unable to secure a publisher for her second volume of poetry in her short lifetime. However, there were at least four posthumous editions of her poems, and a collection of her letters were printed in 1864, many decades after her death. Phillis died on December 5, 1784, from complications due to childbirth. She was in her early thirties.

. . . . . . . . . .

Colonial Boston, image courtesy of thehistorycat-us.com

. . . . . . . . . .

Contemporary view of Phillis Wheatley’s poetry

The consensus of modern and contemporary literary critics seems to be that Phillis Wheatley an important American poet, if not a great one. It also has to be taken into account that as an enslaved person, even one that received such an exceedingly rare education there must have been significant constraints on her freedom of expression.

Some contemporary critics have not been kind to Phillis Wheatley’s poetic work, the common complaint being that her work was a simplistic paean to white, patriarchal dominance and colonialism.

An essay on Phillis Wheatley’s poetry by Megan Mulder gives a balanced perspective on her work, stating that the “historical context is important to an understanding of Wheatley’s poetry.

In the 18th century, the highest form of artistic expression was poetry in the classical mode. Phillis’s formal language and classical allusions may sound stilted to modern readers, but it was vital that she prove her ability to write in this style.”

Further, Mulder states, “Phillis’s religious sensibility is also an important aspect of the Poems. She was by all appearances genuinely devout in the Calvinist, evangelical Christianity of her Boston community.

This too gave the lie to assertions that Africans lacked moral sensibility, and it lent support to evangelicals’ arguments that slaves should be taught to read the Bible and participate fully in religious life.”

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. concluded that “If Wheatley stood for anything, it was the creed that culture was, could be, the equal possession of all humanity. It was a lesson she was swift to teach, and that we have been slow to learn.”

More about Phillis Wheatley

On this site

- 10 Poems from Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

- The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fannone Jeffers: A Review

- James Weldon Johnson’s Analysis of Phillis Wheatley’s Poetry

Major Works and Best-Known Poems

- “An Elegiac Poem on the Death of George Whitefield, Chaplain to the Countess of Huntingdon” (1770)

- Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of Boston (London, 1773; Albany, 1793; republished as The Negro Equalled by Few Europeans)

- “Elegy Sacred to the Memory of Dr. Samuel Cooper” (1784)

- Letters of Phillis Wheatley (Boston, 1864)

More information and sources

- Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral on Wikipedia

- Biography.com

- The Slave Girl Who Became a Literary Sensation

- Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) on Project Gutenberg

Leave a Reply