12 Iconic Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

By Taylor Jasmine | On April 27, 2019 | Updated April 29, 2023 | Comments (17)

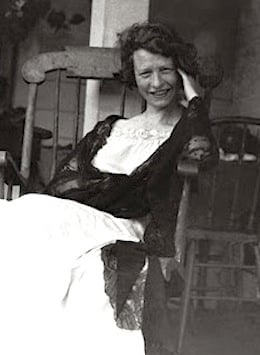

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892 – 1950) has long been regarded as a major twentieth-century figure in the genre of poetry. Here is a selection of 12 poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay from some of her earlier collections.

Vincent, as her family and friends called her, was introduced by her mother to great works of literature from an early age, especially poetry by Shakespeare, Keats, Longfellow, Shelley, and Wordsworth.

At age of sixteen she compiled a dozen or so poems into a copybook and presented them to her mother as The Poetical Works of Vincent Millay.

In 1912, encouraged by her mother, Vincent, then nineteen, entered her poem, “Renascence” to a poetry magazine that was sponsoring a contest. It would publish winning entries in a book to be titled The Lyric Year.

“Renascence” came in fourth and didn’t win the cash prizes offered to the top three entries, (which created quite a literary scandal). Still, the poem garnered her a great deal of attention, launched her writing career, and led to a full scholarship to Vassar College.

The poems included this listing:

- Tavern

- Sorrow

- Euclid Alone Has Looked

- First Fig

- Ebb

- Song of a Second April

- Spring

- Departure

- The Betrothal

- Dirge Without Music

- Love is Not All

- The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver

A Few Figs from Thistles (1921) explored female sexuality, among other themes. Second April (also 1921) dealt with heartbreak, nature, and death.

In 1923, Millay’s fourth volume of poems, The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver, won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. She was the first woman to win a Pulitzer, and only the second person to receive the prize for poetry.

Edna St. Vincent Millay achieved the status of superstar status, something that was — and still is — rare for a poet. Throughout the 1920s, she recited to enthusiastic, sold-out crowds during her many reading tours at home and abroad. An essay by Holly Peppe, Millay’s literary executor, encapsulated her appeal:

“For the disillusioned post-war youth who considered her their spokesperson for women’s rights and social equality, Millay represented the rebellious spirit of their generation.

Indeed, though she favored traditional poetic forms like lyrics and sonnets, she boldly reversed conventional gender roles in poetry, empowering the female lover instead of the male suitor, and set a new, shocking precedent by acknowledging female sexuality as a viable literary subject.”

Perhaps she did burn her candle at both ends, as described in one of her most famous poems, “First Fig” (which is included in this post) — as she didn’t live a long life.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 13 Love Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

More poetry by Edna St. Vincent Millay on this site

- Renascence and Other Poems (1917, full text)

- A Few Figs From Thistles (1921; full text)

- 10 Spring-Themed Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . . . .

Tavern

I'll keep a little tavern

Below the high hill's crest,

Wherein all grey-eyed people

May set them down and rest.

There shall be plates a-plenty,

And mugs to melt the chill

Of all the grey-eyed people

Who happen up the hill.

There sound will sleep the traveller,

And dream his journey's end,

But I will rouse at midnight

The falling fire to tend.

Aye, 'tis a curious fancy—

But all the good I know

Was taught me out of two grey eyes

A long time ago.

(from Renascence and Other Poems, 1917; analysis of "Tavern")

Sorrow

Sorrow like a ceaseless rain

Beats upon my heart.

People twist and scream in pain,—

Dawn will find them still again;

This has neither wax nor wane,

Neither stop nor start.

People dress and go to town;

I sit in my chair.

All my thoughts are slow and brown:

Standing up or sitting down

Little matters, or what gown

Or what shoes I wear.

(from Renascence and Other Poems, 1917;

analysis of "Sorrow")

EUCLID ALONE HAS LOOKED

Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare.

Let all who prate of Beauty hold their peace,

And lay them prone upon the earth and cease

To ponder on themselves, the while they stare

At nothing, intricately drawn nowhere

In shapes of shifting lineage; let geese

Gabble and hiss, but heroes seek release

From dusty bondage into luminous air.

O blinding hour, O holy, terrible day,

When first the shaft into his vision shone

Of light anatomized! Euclid alone

Has looked on Beauty bare. Fortunate they

Who, though once only and then but far away,

Have heard her massive sandal set on stone.

(From The Harp-Weaver and Other Poems, 1922;

Sonnets, IV-XXII

. . . . . . . . . .

Renascence (1912 poem) by Edna St. Vincent Millay

. . . . . . . . . . .

First Fig

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

(from A Few Figs from Thistles, 1921; analysis of "First Fig")

. . . . . . . . . .

Ebb

I know what my heart is like

Since your love died:

It is like a hollow ledge

Holding a little pool

Left there by the tide,

A little tepid pool,

Drying inward from the edge.

(from Second April, 1921; analysis of "Ebb")

. . . . . . . . . .

Song of a Second April

April this year, not otherwise

Than April of a year ago,

Is full of whispers, full of sighs,

Of dazzling mud and dingy snow;

Hepaticas that pleased you so

Are here again, and butterflies.

There rings a hammering all day,

And shingles lie about the doors;

In orchards near and far away

The grey wood-pecker taps and bores;

The men are merry at their chores,

And children earnest at their play.

The larger streams run still and deep,

Noisy and swift the small brooks run

Among the mullein stalks the sheep

Go up the hillside in the sun,

Pensively,—only you are gone,

You that alone I cared to keep.

(from Second April, 1921)

Spring

To what purpose, April, do you return again?

Beauty is not enough.

You can no longer quiet me with the redness

Of little leaves opening stickily.

I know what I know.

The sun is hot on my neck as I observe

The spikes of the crocus.

The smell of the earth is good.

It is apparent that there is no death.

But what does that signify?

Not only under ground are brains of men

Eaten by maggots.

Life in itself

Is nothing,

An empty cup, a flight of uncarpeted stairs.

It is not enough that yearly, down this hill,

April

Comes like an idiot, babbling and strewing flowers.

(From Second April, 1921)

. . . . . . . . . .

Departure

It's little I care what path I take,

And where it leads it's little I care,

But out of this house, lest my heart break,

I must go, and off somewhere!

It's little I know what's in my heart,

What's in my mind it's little I know,

But there's that in me must up and start,

And it's little I care where my feet go!

I wish I could walk for a day and a night,

And find me at dawn in a desolate place,

With never the rut of a road in sight,

Or the roof of a house, or the eyes of a face.

I wish I could walk till my blood should spout,

And drop me, never to stir again,

On a shore that is wide, for the tide is out,

And the weedy rocks are bare to the rain.

But dump or dock, where the path I take

Brings up, it's little enough I care,

And it's little I'd mind the fuss they'll make,

Huddled dead in a ditch somewhere.

"Is something the matter, dear," she said,

"That you sit at your work so silently?"

"No, mother, no—'twas a knot in my thread.

There goes the kettle—I'll make the tea."

(from The Harp Weaver and Other Poems, 1923)

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

The Betrothal

Oh, come, my lad, or go, my lad,

And love me if you like!

I hardly hear the door shut

Or the knocker strike.

Oh, bring me gifts or beg me gifts,

And wed me if you will!

I'd make a man a good wife,

Sensible and still.

And why should I be cold, my lad,

And why should you repine,

Because I love a dark head

That never will be mine?

I might as well be easing you

As lie alone in bed

And waste the night in wanting

A cruel dark head!

You might as well be calling yours

What never will be his,

And one of us be happy;

There's few enough as is.

(from Poetica Erotica; Boni and Liveright, 1921)

. . . . . . . . . .

Dirge Without Music

I am not resigned to the shutting away of loving hearts in the hard ground.

So it is, and so it will be, for so it has been, time out of mind:

Into the darkness they go, the wise and the lovely. Crowned

With lilies and with laurel they go; but I am not resigned.

Lovers and thinkers, into the earth with you.

Be one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.

A fragment of what you felt, of what you knew,

A formula, a phrase remains,—but the best is lost.

The answers quick and keen, the honest look, the laughter, the love,—

They are gone. They are gone to feed the roses. Elegant and curled

Is the blossom. Fragrant is the blossom. I know. But I do not approve.

More precious was the light in your eyes than all the roses in the world.

Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

(From The Buck in the Snow and Other Poems, 1928; analysis of "Dirge Without Music")

. . . . . . . . . .

Love is Not All

Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

And rise and sink and rise and sink again;

Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath,

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

Even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

Pinned down by pain and moaning for release,

Or nagged by want past resolution's power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It well may be. I do not think I would.

(From Fatal Interview, 1931; Analysis of "Love is Not All")

. . . . . . . . . .

The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver

“Son,” said my mother,

When I was knee-high,

“You’ve need of clothes to cover you,

And not a rag have I.

“There’s nothing in the house

To make a boy breeches,

Nor shears to cut a cloth with

Nor thread to take stitches.

“There’s nothing in the house

But a loaf-end of rye,

And a harp with a woman’s head

Nobody will buy,”

And she began to cry.

That was in the early fall.

When came the late fall,

“Son,” she said, “the sight of you

Makes your mother’s blood crawl,—

“Little skinny shoulder-blades

Sticking through your clothes!

And where you’ll get a jacket from

God above knows.

“It’s lucky for me, lad,

Your daddy’s in the ground,

And can’t see the way I let

His son go around!”

And she made a queer sound.

That was in the late fall.

When the winter came,

I’d not a pair of breeches

Nor a shirt to my name.

I couldn’t go to school,

Or out of doors to play.

And all the other little boys

Passed our way.

“Son,” said my mother,

“Come, climb into my lap,

And I’ll chafe your little bones

While you take a nap.”

And, oh, but we were silly

For half an hour or more,

Me with my long legs

Dragging on the floor,

A-rock-rock-rocking

To a mother-goose rhyme!

Oh, but we were happy

For half an hour’s time!

But there was I, a great boy,

And what would folks say

To hear my mother singing me

To sleep all day,

In such a daft way?

Men say the winter

Was bad that year;

Fuel was scarce,

And food was dear.

A wind with a wolf’s head

Howled about our door,

And we burned up the chairs

And sat on the floor.

All that was left us

Was a chair we couldn’t break,

And the harp with a woman’s head

Nobody would take,

For song or pity’s sake.

The night before Christmas

I cried with the cold,

I cried myself to sleep

Like a two-year-old.

And in the deep night

I felt my mother rise,

And stare down upon me

With love in her eyes.

I saw my mother sitting

On the one good chair,

A light falling on her

From I couldn’t tell where,

Looking nineteen,

And not a day older,

And the harp with a woman’s head

Leaned against her shoulder.

Her thin fingers, moving

In the thin, tall strings,

Were weav-weav-weaving

Wonderful things.

Many bright threads,

From where I couldn’t see,

Were running through the harp-strings

Rapidly,

And gold threads whistling

Through my mother’s hand.

I saw the web grow,

And the pattern expand.

She wove a child’s jacket,

And when it was done

She laid it on the floor

And wove another one.

She wove a red cloak

So regal to see,

“She’s made it for a king’s son,”

I said, “and not for me.”

But I knew it was for me.

She wove a pair of breeches

Quicker than that!

She wove a pair of boots

And a little cocked hat.

She wove a pair of mittens,

She wove a little blouse,

She wove all night

In the still, cold house.

She sang as she worked,

And the harp-strings spoke;

Her voice never faltered,

And the thread never broke.

And when I awoke,—

There sat my mother

With the harp against her shoulder

Looking nineteen

And not a day older,

A smile about her lips,

And a light about her head,

And her hands in the harp-strings

Frozen dead.

And piled up beside her

And toppling to the skies,

Were the clothes of a king’s son,

Just my size.

(from The Harp Weaver and Other Poems, 1923; analysis of "The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver")

More about the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay

- American Poems (dozens of entries)

- Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Poetry Has Been Eclipsed by Her Personal Life — Let’s Change That

- Poetry Foundation

More poetry by Edna St. Vincent Millay on this site:

- Renascence: and Other Poems (1917) – full text

- A Few Figs From Thistles (1921; full text)

- 10 Spring-Themed Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Second April (1921) – full text

- The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver (1922) – full text

I don/t understand “God’s World”, –My soul is all but out of me, let all no burning bush, prithee, let no bird call.

Thomas, that poem is part of Renascence and other Poems whose full text is reprinted on this site. As for that particular poem, you’ll find an analysis here: https://poemanalysis.com/edna-st-vincent-millay/gods-world/ I hope that helps! https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/full-texts-of-classic-works/renascence-and-other-poems-by-edna-st-vincent-millay-full-text/

heartfelt and so poetic for all ages to savor and repeat whenever you need an arm to rest on : Thanks , Bill

Thanks, Bill. ESVM is so timeless …

Question. What Edna poem has the lines a thief purloin? Is it poem called THE COIN?

Danny, the poem you’re looking for isn’t by Edna, but by Sara Teasdale. It is called The Coin, and you’ll find it here: https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/coin-3

There is a mediocre film called “The Hero” staring Sam Elliot about an aging actor coping with the news that he has cancer. Near the end of the film, a woman friend reads a poem to him by Edna St. Vincent Millay, Dirge Without Music. The poem is much, much better than the film. I am 82 and I Do Not have cancer, but I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

David, thank you for bringing this poem to my attention. How interesting that it was part of a film. Reading it is quite the experience, especially the last stanza:

Down, down, down into the darkness of the grave

Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave.

I know. But I do not approve. And I am not resigned.

For the entire poem: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52773/dirge-without-music

I first came across Edna St. Vincent Millay almost 70 years ago when I was an underdergrad. studying literature in Bombay, India. Today, at 87, after teaching literature at a midwest university all thgese years, I still enjoy her poetry and just bought a vinyl disc of her poems. Among my favorite are “On First Hearing A Symphony by Beethoven” and “What Lips My Lips Have Kissed”.

Thank you for this selection.

Wow, a vinyl of ESVM … what a treat that must be! Thanks for your comment, and input!

My favourite of hers is “time does not bring relief: you all have lied” = every time I read it I end up in tears – what a wonderful poet.

Mine as well.

Hi what poem is this line from please ?

Lori, can you clarify what you’re looking for?

She was well before her time, but the Ballad of the Harp Weaver, brought tears to my eyes. So true, of early America, but also today!!! She was seldom mentioned when I attended school, to graduate 1958. I missed those lovely charming stories. Will enjoy them now. Thank you. Saw her story in The Pittsburgh Post_Gazette, this Sunday Pg. D-7. Pittsburgh PA

Thanks so much for writing this – I will always adore and love Vincent!

Thanks, Nancy — I wish she was more widely read and discussed than she is. Definitely still an iconic figure, and so far ahead of her time.