Sic Transit Gloria Mundi — an early poem by Emily Dickinson (1852)

By Nava Atlas | On December 29, 2020 | Updated August 29, 2022 | Comments (1)

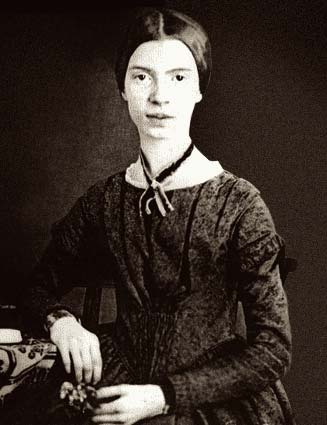

“Sic Transit Gloria Mundi” was the first poem by Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886) to be published. Without her prior knowledge or consent, it appeared in the February 20, 1852 issue of the Springfield Daily Republican newspaper.

Emily, then age 21, wasn’t pleased. Still a budding poet, she was not at all interested in publication. In her teens and twenties, she may have been reserved and a bit shy, but nothing to hint at how reclusive she would become in her later years. In fact, she and her sister Lavinia (Vinnie) enjoyed quite an active social life in their youth.

One of the highlights of the year was Valentine’s Day, an occasion to brighten the long, cold winters of their home town, Amherst, Massachusetts. Young people enjoyed parties and lavish handmade cards and letters created for a holiday that wasn’t nearly as exclusive to couples as it has since become.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Emily Dickinson

. . . . . . . . .

Emily was inspired to write the long, lively poem, still among her best known, that begins “Sic transit Gloria mundi.” Translated as “This passes the glory of the world,” here’s how it happened to get published, according to Krystyna Poray Goddu, in Becoming Emily: The Life of Emily Dickinson (2019):

“February [1852] also saw the usual flurry of Valentine’s Day notes and poems. To Emily’s surprise, her valentine to young William Howland, who had worked in her father’s law firm, was published, anonymously, in the February 20, 1852 issue of the Springfield Daily Republican newspaper.

The valentine, a poem of 17 quatrains (verses with four lines) with the second and fourth lines of each verse rhyming, holds two mysteries. First, to this day nobody knows who sent it to the newspaper.

Second, Emily never showed any special interest in Howland. Why she chose him as the recipient of this long poem is mystifying. The ambitious poem is noteworthy for being so cleverly written and technically well done.”

Though Howland never owned up to it, as the poem’s recipient, it might be logical to assume that he was the culprit who submitted it to the paper.

All through her life, Emily remained disinterested in having her poems published, though she enjoyed sharing a small number with those she loved or trusted. After her death, over a thousand poems were discovered by her sister Lavinia. By some estimates the number of poems were 1,100; other sources state that it was closer to 1,800.

Analyses of Sic transit gloria mundi

- Blogging Dickinson

- Emily Dickinson’s Valentines (preview on Jstor)

. . . . . . . . . .

Sic transit gloria mundi

“Sic transit gloria mundi,”

“How doth the busy bee,”

“Dum vivimus vivamus,”

I stay mine enemy!

Oh “veni, vidi, vici!”

Oh caput cap-a-pie!

And oh “memento mori”

When I am far from thee!

Hurrah for Peter Parley!

Hurrah for Daniel Boone!

Three cheers, sir, for the gentleman

Who first observed the moon!

Peter, put up the sunshine;

Patti, arrange the stars;

Tell Luna, tea is waiting,

And call your brother Mars!

Put down the apple, Adam,

And come away with me,

So shalt thou have a pippin

From off my father’s tree!

I climb the “Hill of Science,”

I “view the landscape o’er;”

Such transcendental prospect,

I ne’er beheld before!

Unto the Legislature

My country bids me go;

I’ll take my india rubbers,

In case the wind should blow!

During my education,

It was announced to me

That gravitation, stumbling,

Fell from an apple tree!

The earth upon an axis

Was once supposed to turn,

By way of a gymnastic

In honor of the sun!

It was the brave Columbus,

A sailing o’er the tide,

Who notified the nations

Of where I would reside!

Mortality is fatal—

Gentility is fine,

Rascality, heroic,

Insolvency, sublime!

Our Fathers being weary,

Laid down on Bunker Hill;

And tho’ full many a morning,

Yet they are sleeping still,—

The trumpet, sir, shall wake them,

In dreams I see them rise,

Each with a solemn musket

A marching to the skies!

A coward will remain, Sir,

Until the fight is done;

But an immortal hero

Will take his hat, and run!

Good bye, Sir, I am going;

My country calleth me;

Allow me, Sir, at parting,

To wipe my weeping e’e.

In token of our friendship

Accept this “Bonnie Doon,”

And when the hand that plucked it

Hath passed beyond the moon,

The memory of my ashes

Will consolation be;

Then, farewell, Tuscarora,

And farewell, Sir, to thee!

. . . . . . . . . .

See also: 10 Well-Loved Poems by Emily Dickinson

Timelessness. Lumen quod nunquam peribit.