What (Jane Austen’s) Women Want: Exploring Questions We’re Still Asking

By Janet Saidi | On March 10, 2022 | Updated August 23, 2022 | Comments (1)

If you’re like me, you’ve many times had to explain what Jane Austen is really about — you might find yourself explaining to friends who just don’t get it, that Austen is not all about finding a man who’s wealthier and more powerful than you are, to marry.

This musing, pondering the question of what Jane Austen’s women want, is excerpted from The Austen Connection, reprinted by permission.

Sure, these novels follow the traditional Marriage Plot. These novels may have invented the plot as we know it today.

As we’ve said before and will point out often in these letters, the stories also — while not technically Romance-genre stories — introduce, build on, and play off of our favorite Romantic Tropes, from the hate-to-love or friends-to-lovers storylines, to the Alpha male, forbidden love, and proximity plots.

But we also know that within this scaffolding of she-who-identifies-as-girl-meets-complicated-person-who-identifies-as-boy, there is a lot of meandering to get to our much-anticipated engagement, and there’s also some analysis after the Love Declaration, where Austen shows us what she’s been doing all the while.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

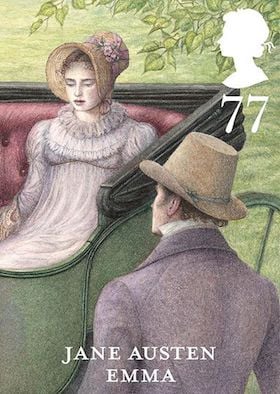

And this post-game analysis takes place in the books, friends, not so much in the screen adaptations. That’s because Knightley and Emma apologizing to each other and explaining what they’ve learned through their experiences in the preceding scene, just doesn’t make good cinema. But it’s actually pretty sexy reading.

So, I thought we could discuss what all this meandering — the subtext within Austen’s actual text — is about, and where Austen is trying to take us, as her heroines, and their leading guys, wander through the wilderness of society, and customs, and class, and humiliations, to get to their unexpected (or entirely expected, by us the reader) happy ending, with a hard-won, successful match: a marriage.

So here’s a very simple question: What do Austen women want?

For me, the question leads us to some unexpected places — places that go well beyond the Courtship and Marriage plot. Places that take us on a tour of key issues those identifying as women have even today. Or especially — you might say — today.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

1. See me

The first thing I’ll argue here that Jane Austen’s women want is simply to be seen as human.

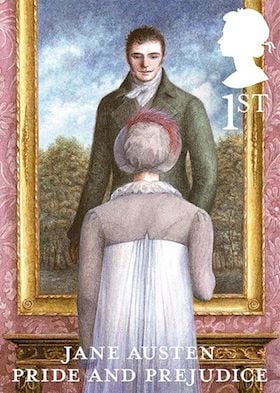

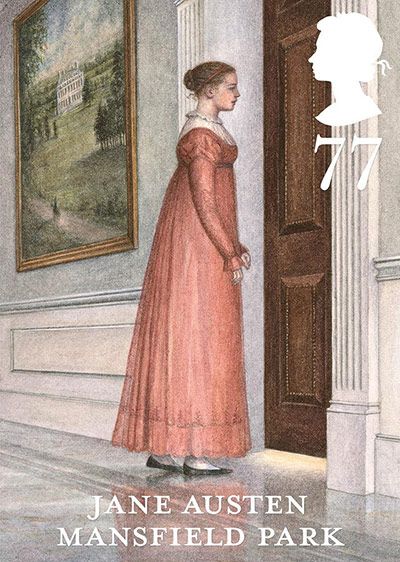

I know that sounds a bit basic, maybe even sarcastic — but when you break down what characters like Lizzy Bennet and Fanny Price actually say, you realize they want to be seen, and they want to be seen as rational, human creatures.

And they say as much.

When Elizabeth Bennet implores Mr. Collins, during his proposal, to see her as “rational” she is drawing, it’s assumed, from Mary Wollstonecraft’s famous treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792, when Jane Austen was seventeen years old.

This plea of Elizabeth’s to be seen as rational — and not be taken as a flattering, manipulative “lady” of fashion in search of gallantry or advantage — cannot be overestimated: It is truly central to what Austen’s heroines, and what Austen herself wanted.

In Vindication, Wollstonecraft urges women not to buy in to the roles society creates for middle- and upper-class women — to be pretty playthings who responded to gallantry, and in doing so either became victims or deployed what little agency they have toward manipulation.

In the intro to Vindication, Wollstonecraft paints an ugly picture of the women her 18th-century world had created: women who, taken in by the flattery of men, “do not seek to obtain a durable interest in their hearts, or to become the friends of the fellow creatures who find amusement in their society.”

Lucy Steele, anyone? Insert your favorite Austen mean-girl here.

To me, the entire sense vs. sensibility tension that drives Austen’s characters and plots reads like a fictionalization of Wollstonecraft’s premise in Vindication.

Wollstonecraft says — Listen up: This construct you’re putting women into is bad for women, and it’s bad for men. It’s bad for everyone. It’s just bad.

Austen says this over and over too. But she says it differently, and through fiction.

Wollstonecraft’s message is: Look what happens to us when you don’t provide women with opportunities for education and agency — you end up wasting half of society’s resources, and everyone is unhappy in the bargain.

But Austen gives us a lopsided mirror image of the bleak picture painted by Wollstonecraft, showing us: Look what happens when do you have educated women, like Elizabeth Bennet and Elinor Dashwood and Anne Elliot — what you get is strong women with authentic affections who are better supporters not only of their families, but can make meaningful contributions to society.

The difference is imagination. The difference is story. Austen creates an imagined world that forces us to see past the real one.

Because Austen was first and foremost an artist — and she continuously deploys her imagination to fashion a better world through art, through fiction. And often, still more than 200 years later, we don’t see it.

But the way Jane Austen does it is a lot more fun.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

2. Just call me Human

Jane Austen’s women are not just intelligence that is forcefully conveyed — think Emma Woodhouse, Elizabeth Bennet, and Fanny Price (Mansfield Park) who, as we’ve said, are in their various ways the Smartest Person in the Room.

But Austen’s stories flip the script, with feeling — the radical interiority of her characters that is urged on every reader also forcefully puts upon the reader the feelings, the cares, the loves, the doubts, the triumphs, of these young women characters.

We empathize. And empathy leads to understanding.

This is the powerful thing Austen is doing — that Wollstonecraft is doing too, but again Mary is doing it through political writing and Jane is doing it through storytelling. (And specifically, one way she’s doing this is through her celebrated stylistic technique of free indirect discourse.)

Rather than Wollstonecraft’s “enfeebled” women – women weakened by frippery, and romance — Austen’s women want to be seen not as Females, but as Humans engaged in and contributing to the vast human enterprise. Not decorations, however well cared for, on the margins of that enterprise.

Sometimes I feel like all of Austen’s literary techniques and dramatic powers are rallied toward this enterprise. She deploys point of view, narration, and an intense interiority of the female perspective, to create empathy, as writers before and since have done.

To do what Austen did in the early 19th century is still considered even today to be radical and innovative — from Toni Morrison and Elena Ferrante to Karl Ove Knausgaard: To show our point of view, and in doing so to reveal our humanity.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

3. Let’s call it a tie (or ‘companionate marriage’)

Of all people, it is often the leading men that take Austen’s challenge to reason and humanity seriously, in her novels.

It’s easy to dismiss Mr. Darcy, Henry Tilney, and Mr. Knightley as chivalric, powerful suitors.

But they defy — and deftly undercut — the mold: They look the part, but their “manners” are blunt and challenging in a way that throws off notions of chivalry. (Charlotte Brontë took this to the extreme with Rochester and was called a “sexual delinquent” for doing so by a 19th century reviewer — but that’s a topic for another day, friends!)

Austen’s leading men are also affectionate, understanding, and always straightforwardly candid. Austen places them in opposition to gallant falsity of the Wickhams, the Willoughbys, and the Frank Churchills.

Knightley and Darcy, our most famous leading men in Austen, are perhaps the biggest examples of blunt, candid, challenging truthfulness mixed with genuine feeling. And it’s why they are also so appealingly — there’s no better word for it — sexy.

Even Henry Tilney, who has lots more experience than naïve Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey, treats her respectfully, even while challenging her wild, Ann Radcliffe-inspired imaginings.

In Emma, the character that most challenges the Female Ideal of idle useless playfulness is Knightley himself.

So, what’s going on here?

First of all, Austen is so good at her job that we always have to remind ourselves, friends, that it is not of course Knightley who makes the charge to Emma’s governess that our heroine should be more usefully employed and more often opposed — it is Austen giving him his words.

It is always Austen, behind the scenes, putting the words into the mouths of our powerful heroes. And in doing so I think she’s showing that women just might be worth the trouble. It’s jarring to even write that last sentence — but in Regency England this was something that needed to be said: If an astute, wealthy, independent Knightley is clear enough in his head to say that most men do not want to marry silly women, then maybe Austen’s early-19th-century readers would reconsider what after all makes a good wife, and maybe they would pay attention to her and other young women in their life.

They’re invited to do this through the words, and actions, of Knightley. This is what’s going on, friends, when Knightley invites Harriet Smith to dance with him in that infamous swoony scene that rescues Harriet and lifts her beyond the painful public condescension of the Eltons.

Austen is standing up for the women by appealing to the men — in language they understand.

It is always Austen, behind the scenes, putting the words into the mouths of our powerful heroes. And in doing so I think she’s showing that women just might be worth the trouble.

And as we’ve pointed out in these letters and will continue to explore, all the meandering around and toward courtship and marriage in Austen has, for Regency-world readers, an unexpected destination. It is always a union between not only equals — equally strong, equally judge-y, and equally flawed and feeling humans — but also it’s a union that is predicted to be intellectually challenging to each party.

This is one of the things that makes Austen, in the end, a writer of realism rather than romance. The romantic scaffolding is there for all to enjoy — but we also see, along the way, plenty of conflict and conflagration that is going to come from two real people with real passions and real opinions. And that clash is both the romance and the realism.

It’s also what makes people — actually human ones — stronger.

Austen repeatedly shows that marriage between two people is an opportunity to improve, or not: The Bennetts’ marriage makes each of them worse; marriage between John and Fanny Dashwood makes each more selfish and weaker; marriage between Emma and Knightley will make each more generous and engaging.

Marriage in Austen can be a living nightmare or a benevolent dream. And it is not romance — but education, intelligence, and integrity, mostly of women — that decides it.

So in Austen, a spouse can improve you, and improve your life and that of your family. It can even increase your status and popularity, which in this Regency world is a tool for survival.

So, in Jane Austen’s world, an equal, candid, challenging marriage is a survival skill, and, also, a lot more fulfilling and fun.

Read the rest of What (Jane Austen’s) Women Want on the Austen Connection.

Contributed by Janet Saidi. Janet is a public-radio journalist with a couple of degrees in Literature, and has written about arts and culture for NPR, the BBC, the Christian Science Monitor, and the Los Angeles Times. Join the conversations on all things Jane Austen at the Austen Connection newsletter, @AustenConnect on Twitter, and at @austenconnection on Instagram and Facebook. And you can follow the Austen Connection podcast on Spotify and Apple.

This essay seems to take the long way around the barn, to say that women still yearn for a reality that doesn’t exist in biology. As they say, “We promise according to our hopes and perform according to our fears”. Hormones and genetics call an invisible tune that has directed the dance between the sexes, and caused men and women to equally disappoint each other. Romance is a farce used to distract ourselves from the brutality of being biological beasts.