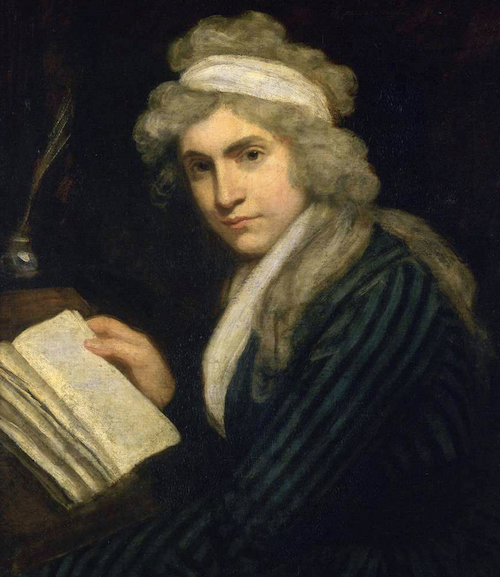

Mary Wollstonecraft, Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

By Nava Atlas | On March 20, 2019 | Updated August 25, 2022 | Comments (0)

Mary Wollstonecraft (April 27, 1759 – September 10, 1797) was a British author of fiction and nonfiction, philosopher, and women’s rights advocate.

Though her body of work was fairly substantial, including many essays, a history of the French Revolution, and some fiction, she’s now primarily known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

She was the mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (later known as Mary Shelley), the author of Frankenstein; sadly, she died a few days after giving birth to her namesake.

An unstable childhood and youth

Born in the Spitalfields section of London, her father, Edward John Wollstonecraft, frittered away his inherited fortune. He bullied his children and beat and raped his wife, Elizabeth Dixon, in the midst of his drunken rages. While in her teens, Mary sat guard at her mother’s door to try to protect her from her father.

There were six siblings in the household. The eldest, Edward, eventually became an attorney who practiced in London. There were two other brothers, and three sisters, Mary, Everina, and Eliza. Their father continued to make life intolerable for his family as his fortunes deteriorated with each failed venture.

Of the Wollstonecraft children, Mary and Eliza were thought to be quite talented, but they acquired little in terms of formal education. When their mother died in 1780, Mary, at age 21, resolved with her sister to become a teacher.

Finding her father’s household intolerable, she moved in with her friend Fanny Blood, only to find that her friend’s father was just as nefarious as her own. She derived some comfort in assisting Fanny’s mother in doing needlework as a trade, but not many years later, lost her dear friend when she died in childbirth

Her sister Everina went to work keeping house for their brother Edward. Eliza accepted an offer of marriage while still quite young as a way to escape her miserable home life. Marriage was no salve, as her husband, a Mr. Bishop, was abusive.

Eliza’s misfortune was portrayed later in Mary’s thinly veiled novel fragment, The Wrongs of Woman, or Maria. Things got so bad that Eliza went into hiding until she could obtain a legal separation. In 1783, Mary and Everina started a school at Newington Green, though it lasted only two years.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Beginning a literary career

After this short stint as a teacher, Mary worked as a lady’s companion and governess, and quickly realized that she was ill-suited for these traditional female occupations. She was frustrated at the lack of options for women to make a living and wrote of this quandary in one of her first published works, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters.

Mary was determined to do what she most wanted — to become a writer. There were few women who were able to support themselves by their pen, so her ambition was nothing less than radical. But as she wrote to Everina, she wished to become “the first of a new genus.”

Mary settled in London and found a position with the progressive publisher Joseph Johnson as a reader and translator. The occupation not only suited her well, but had other benefits. It gave her the opportunity to connect with the literary circles of the day, and with her earnings, she helped her siblings, especially Everina.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

In 1792, Mary published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. It enjoyed some initial success and was translated into French.

Its central thesis was an argument for equality of men and women: Men and women, in her view, are born with the ability to reason, and therefore power and influence should be equally available to all regardless of gender. This was quite a unique and radical view for its time.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is considered one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In her preface to Mary Wollstonecraft: A Biography (1972), women’s studies pioneer Eleanor Flexner wrote about her subject that she:

“… articulated her protest and her ideas of what education and equality of opportunity might do for society as a whole … It is not given to many books to exert as powerful an influence as A Vindication has done, although its effect was delayed and for decades it was largely unread.”

Read more of this appreciation of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

. . . . . . . . .

Quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

. . . . . . . . .

Gilbert Imlay: Obsessive love

Later in 1792, traveling to Paris alone, Mary met and fell in love with Gilbert Imlay, a commercial speculator, adventurer, and former American army captain during the Revolutionary War.

Getting married in France would have been virtually impossible during the Reign of Terror. King Louis XVI had recently been guillotined, and Britain and France were on the brink of war.

So Mary lived openly with Imlay without marrying. Marriage was unimportant to her, as evidenced in her Letters to Imlay (a posthumously published collection); still, to live with a man as his wife without being married was shocking. And of course, it was the woman who suffered all the societal consequences.

By the end of 1793, the two were living in Havre, France, and on May 14, 1794, Mary gave birth to a daughter, who they named Fanny. Mary continued to write, publishing Historical View of the French Revolution not long after her daughter’s birth.

Imlay was deeply involved in business speculations, which necessitated long periods of separation. Mary’s letters from this time hint at doubts about his feelings for her and suspicions of his infidelity. She recognized the perils of being so attached to a man whose feelings have grown cool:

“I have gotten into a melancholy mood, you perceive. You know my opinion of men in general; you know that I think them systematic tyrants, and that it is the rarest thing in the world to meet with a man with sufficient delicacy of feeling to govern desire.

When I am thus sad, I lament that my little darling, fondly as I dote on her, is a girl. I am sorry to have a tie to a world that for me is ever sown with thorns.”

Mary’s suspicions proved correct. Imlay’s letters grew less frequent and less ardent as he embarked on a new love affair. As Lisa Phillips, author of Unrequited: Women and Romantic Obsession (2015) relates the episode:

“She wrote to him often and with great fervor, trying to convince him of his obligation to continue to love her. He finally asked her to come to London — but not has his partner. Her arranged for her to live in separate furnished lodgings. Soon after she arrived, she tried to kill herself by swallowing laudanum.

After she recovered, Imlay made a startling proposal. He asked her to travel to Scandinavia to negotiate compensation for a cargo of silver he believed had been stolen. The suggestion, in the wake of his betrayal and abandonment, was quite an audacious brush-off.”

And yet, Mary took him up on this scheme, taking their baby on this arduous mission, her sense of purpose helping her to fight the desire to try to kill herself once again.

The story of this tortured, increasingly one-sided affair continued for some time. When their final separation came, Mary, still passionately in love with Imlay, tried to drown herself by plunging off a bridge, but was rescued by a boat that was passing by. Continuing from Unrequited by Lisa Phillips:

“Far away from her beloved, Wollstonecraft could do something with her love. She could be someone new, even with her heavy heart. In Imlay’s presence, she had to face the fact of his rejection. Once she returned to England, she discovered he had taken up with yet another lover.

She tried to kill herself again. This time, she dressed in heavy velvets, weighted her pockets with rocks, and, hoping to sink quickly, jumped off the Putney Bridge into the Thames.”

Eventually, Mary came to her senses and broke off with Imlay in 1796, refusing to take any financial support from him other than a bond that would benefit their daughter.

Not only that, but she asked him to return the letters she wrote him, so full of longing and entreaty. Combining them with the journal entries she kept while traveling in support of Imlay’s business ventures, published a volume titled Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark.

Amazingly, the book was a great success. She continued to write in other forms as well, as a means of self-support as well as a way to return to London’s literary society.

A brief marriage and a fatal birth

She resumed her friendship with William Godwin, who she had met a few years earlier upon beginning to work for Joseph Johnson. Their relationship soon turned romantic. Though both of them were philosophically opposed to traditional marriage, they wed on March 29, 1797. Mary was by then expecting a child.

It was to be a brief marriage. After giving birth to a healthy baby girl, Mary contracted an infection and died eleven days later, age 38, on September 10, 1797. She was buried in the Old St. Pancras churchyard and in 1851, her remains were moved to Bournemouth.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Romantic Outlaws is a fascinating dual biography

of mother and daughter Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley

. . . . . . . . . . .

The legacy of Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft was described as impulsive and enthusiastic, with charm of manner and brilliance of mind. A year after her death, Godwin published the simply titled Memoir. Though it wasn’t his intent to besmirch her reputation, he revealed intimate details of his late wife’s life.

The book detailed her love affairs, illegitimate daughter Fanny, and suicide attempts, and more. All of it was deemed deeply immoral and appalled late-18th-century society, even the more progressive literati. In the preface, Godwin wrote:

“I cannot easily prevail on myself to doubt, that the more fully we are presented with the picture and story of such persons as the subject of the following narrative, the more generally shall we feel in ourselves an attachment to their fate and a sympathy in their excellencies.

There are not many individuals with whose character the public welfare and improvement are more intimately connected than the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.”

Despite Godwin’s intentions of cementing her legacy, the book instead completely destroyed Mary Wollstonecraft’s reputation for the better part of a century. Female novelists of the 19th century, ironically, were the most vicious. They created unlikeable, amoral female characters and didn’t hide the fact that they were modeled from what they knew of Mary.

Fortunately, Mary Wollstonecraft’s legacy as a pioneering feminist philosopher was restored during the second-wave feminist movement of the 1970s, and she is often credited as an important influence on modern-day feminist theory.

More about Mary Wollstonecraft

On this site

- Quotes from A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: An Appreciation

Major works

- Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787)

- Mary: A Fiction (1788)

- Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

- Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794)

- Letters Written in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark (1796)

- Letters to Imlay (1879; posthumous)

- The Wrongs of Women, or Maria (novel fragment; posthumous, 1798)

Biographies

- The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft by Claire Tomalin (1975)

- Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft by Lyndall Gordon (2006)

- Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft

and Mary Shelley by Charlotte Gordon (2015)

More information

Read and listen

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s works on Librivox

- Public domain ebook ofA Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Leave a Reply