Signed Genêt: Janet Flanner’s Letters from Paris

By Elodie Barnes | On December 1, 2021 | Updated March 15, 2025 | Comments (0)

Janet Flanner (1892 – 1978) was an American writer and journalist, best known for her fifty-year stint as The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent. Writing under the pen name Genêt, she became synonymous with the inter-war expatriate scene in Paris, and her prose style epitomized and influenced the magazine’s journalism to such an extent that it came to be known as “The New Yorker style.”

Over the years, her work for the magazine extended far beyond Paris into broader European politics and culture, encompassing a regular “London letter” and several one-off pieces from a war-scarred Germany.

Her legacy was such that even she was forced to acknowledge, towards the end of her life, that she had created “the form which all other foreign letters consolidated by copying my copy…” and Glenway Westcott called her “the foremost remaining expatriate writer of the Twenties.”

Beauty with a capital “B”

Janet was in her late twenties when she decided to move abroad, leaving behind her Indiana roots, her family, and her husband Lane Rehm (whom she would amicably divorce some years later).

Having grown up in the stifling comfort of the Indianapolis middle class, she had made her first break when she joined the Indianapolis Star as its first cinema reporter, and her second when she moved to New York to be with Lane, then making his way as an artist in Greenwich Village.

The third break would be permanent. Together with her new partner, Solita Solano (née Sarah Wilkinson), she chose to travel across the Atlantic in an attempt to find “beauty, with a capital B … I was consumed by the own appetite to consume — in a very limited way, of course, the beauties of Europe.”

And, although she didn’t articulate it at the time, she was also attempting to find freedom from the professional, personal, and sexual restrictions that she already knew American society would impose, even in the bohemian enclave of Greenwich Village. As a lesbian writer who had no desire to hide, she felt as if America had nothing to offer.

After some traveling through Europe, they finally settled in Paris in autumn 1922, taking rooms at the small Hôtel Saint-Germain-des-Prés at 36 rue Bonaparte. The hotel would be their base for the next sixteen years.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Janet Flanner

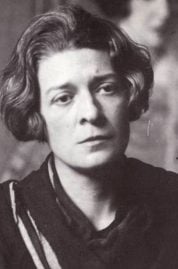

(1927 portrait by Berenice Abbott, Clark Art Institute)

. . . . . . . . . .

Making a home in Paris

Both Janet and Solita quickly made friends among the American expatriates in the city. F. Scott Fitzgerald was a regular visitor to their hotel, as was a young Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway and Janet got on particularly well and talked a lot about their writing: after Janet had written probably her one and only sports piece — on bullfighting, a subject that was not yet so close to Hemingway’s heart as it would be in later years — he told her:

“…like a member of my family, I just want you to know that if a journalistic prize is ever given for the worst sportswriter of the western world, I’m going to see you get it, pal, for you deserve it. You’re perfectly terrible.”

They were also part of the community of women who gravitated towards the Left Bank, attending Natalie Barney’s Friday salons and Gertrude Stein’s Saturday gatherings and regularly visiting Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Co. bookshop.

Through Natalie Barney, they also met Germaine Beaumont (a French writer also rumored to be the lover of Colette), Dolly Wilde, and Djuna Barnes. All three women would become close friends; Barnes would later immortalize Janet and Solita as the journalists “Nip and Tuck” in her notorious Ladies Almanack, a satire on the lesbian circles that surrounded Barney’s salon.

. . . . . . . . .

Solita Solano in 1930

. . . . . . . . . .

The beginning of the relationship of a lifetime

Although she loved to talk about literature, Janet didn’t very often admit that she was writing herself. Instead, she declared that she would be perfectly happy to spend her life at the Deux Magots cafe, only writing a novel “if the spirit moved” her.

But she was in fact dedicating quite a bit of time to writing: there were poems and some journalistic articles that she dismissed as hack pieces, and she was also working on her novel, The Cubical City.

The novel was taken by George Putnam in late 1924 and eventually published in 1926, but by that time Janet was well and truly immersed in a proposal which had come her way the previous year, from her friend Jane Grant in New York. It was this which would set the course of the rest of Janet’s life.

Jane was a journalist for the New York Times; her husband Harold Ross had just founded The New Yorker. The first issue had been published on February 21, 1925. With its stated aims to “reflect the metropolitan life, to keep up with events and affairs of the day, to be gay, humorous, satirical, but to be more than just a jester,” the magazine had high ideals but not much solid backing.

For the next few months, Jane and Harold were ruthless in hiring and firing employees, all the while scouring the published press for any writers whose style might suit. Belatedly, Jane remembered Janet’s comment about spending the rest of her life in the Deux Magots.

She and Ross decided to put Janet’s commitment to the test by asking her to become the magazine’s Paris correspondent, offering thirty-five dollars per submission for a fortnightly letter of about a thousand words:

“He [Ross] wants anecdotal and incidental stuff on places familiar to Americans and on people of note whether they are Americans or internationally prominent – dope on fields of the arts and a little on fashions…there should be lots of chat about people…and in it all he wants a definite personality injected. In fact, any one of your letters would be just the thing.”

These pieces were to appear anonymously, a policy that Ross adopted with all of the magazine’s writers. He did not, he said, want to advertise the magazine’s content or its writers, leaving the name of the magazine to speak for itself, and only the editors were ever attributed by real names.

For Janet, he came up with what appeared to be a Gallicized version of Janet — Genêt — although perhaps he was also thinking of Edmond-Charles-Édouard Genêt, the first French Ambassador of the French Republic to the United States, and a prolific letter writer himself. Either way, Janet was flattered and sent her first submission on September 13, 1925.

. . . . . . . . . .

![]()

. . . . . . . . . .

The formation of a style

Janet’s early Paris letters, in keeping with the magazine’s satirical bent and Ross’s stated wishes, were a sparkling mixture of anecdotes, social observations, and wry commentary on Paris life. Full of doubt about her ability to sustain fiction, she felt as if she had found her niche, a way of writing the world around her without the vagaries and complexities of too much emotion or plot.

As Genêt she reported on literature, art, fashion, publishing, and the streets of Paris. She wrote on gallery openings and the latest movies, on the races at Longchamps and Colette’s favorite restaurant, on Mozart’s letters to his wife and Pierre de Lanux’s collection of lead soldiers.

She described to her readers the glittering nights spent at cabarets on “the hill” (Montmartre), and how dawn broke over the markets at Les Halles with their heady scents of flowers, vegetables, and coffee. In essence, she brought her readers to her Paris, and expected them to fit right in.

But Genêt was also witty and uninvolved: she was apart from almost everything she wrote, a sharp observer ever ready to dissect an experience with her tongue and her pen. Janet believed that Ross wanted her to write about what the French thought, not about what she thought, and so felt that her pieces should exclude the personal as much as possible.

She made no attempt at long-winded explanations or background information, and any opinions of her own were ambiguous.

One of the few times she made her feelings known was in her description of George Antheil’s “Ballet mécanique” as wonderful, but composed entirely of sounds made by three people, “one pounding an old boiler, one grinding a model 1890 coffee grinder, and one blowing the usual 7 o’clock factory whistle and ringing the bell that starts the New York fire department going in the morning.”

She rarely analyzed, but tried to portray experiences in the wittiest way possible: of the 1925 Autumn Salon, she wrote: “After looking at the 3,000-odd canvases, you go out with a feeling that one of your eyes may be orange and the other pink and that one of your shoulders is certainly six inches higher than the other.”

For research, as well as her own experiences and contacts, she read an average of ten French newspapers a day, and she would later credit this regime, along with Ross’s editorship, with teaching her how to write.

From the French journalistic style, and Ross’s passion for grammar and clarity, she learned to trim excess, balance sentences, and make her descriptions as clear as possible.

For the first time, she had deadlines and a purpose, and this gave her discipline to write whereas before she had struggled. Ross demanded a high standard and Janet strove to deliver — she often said that she wrote to please him.

The logistics of a fortnightly letter

During these months she established the routine that she would more or less follow for the next fifty years. Having decided on her topic or topics for that fortnight’s letter and gathered her material, she would then shut herself in her hotel room, sometimes for as long as forty-eight hours.

Solita would often type and edit for her, and, as time went on, other friends would attend events on her behalf, suggest people and places to write about, and help to gather material.

When the letter was finished, Janet would take her copy to the Gare Saint-Lazare, where she could post it on the boat train that, on certain days, connected with a fast New York-bound ship. Once it arrived in New York, Janet very often heard nothing until it was published.

. . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

The challenge of ‘Profiles’

Encouraged by the prospect of more money and by Ross’s determination that she should extend her writing, Janet soon decided to try writing a “Profile” — an almost four thousand-word sketch of a living person that was one of the magazine’s longest-standing features.

A list of eligible Profile names was kept in New York, and editors often assigned them to writers with some original knowledge of or contact with the subject.

For Janet, a Profile was a challenge: the style was expected to be serious and in-depth, and the writer was expected to express more of an opinion beyond witty vignettes. In addition, Profiles were to be signed with the writer’s real name, or a different pseudonym of their choosing.

Her first, on the dancer Isadora Duncan, appeared in January 1927. Janet herself was pleased with the piece, especially considering that she was unused to the longer format. Profiles on novelist Edith Wharton and fashion designer Paul Poiret soon followed.

Duncan and Poiret were attributed to “Hippolyta,” but Janet signed the Wharton profile with her own name. It was the one she was most proud of and was also the one to convince her to finally give up on the idea of a second novel.

If she had started competing with Wharton earlier, she said, she might have achieved something, but she had set her sights too high. Journalism — particularly this form of amusing, sardonic, people-focused journalism — was where her writing talents lay.

Economics and politics

Initially, Janet wasn’t particularly affected by the 1929 Wall Street crash, and her December 4th letter referred to it only as the “recent unpleasantness on Wall Street.” She was also fairly ignorant of politics in general and relied on friends to explain to her about the French party system.

Even when she had come to a basic understanding, she never felt confident in expressing her own opinions and preferred to avoid the topic altogether. In 1930s Europe, however, this was increasingly hard to do.

By 1932, French industrial production had fallen, and unemployment had risen to the point where even Genêt had to acknowledge that, while Paris was “mostly still gay”, there was increasing unrest. One letter from this time was entitled “Political Addenda, Mostly Not Funny.”

In February 1934, there was rioting on the streets of Paris, worse than any that had been seen since the bloody Commune of 1871.

Janet avoided the actual riots but did go to the Place de la Concorde the following day to be confronted with the fallout: bullet-marked stone, the smoking embers of two burned-out buses, and blood streaked across the pavements where the injured had been dragged away.

This marked a turning point in her views on the tone Genêt, and the Paris Letters, should take, and little by little she began to include more political commentary in her letters. She still felt out of her depth, and more often than not relied on others to provide the political knowledge and opinions that she felt she should have herself.

But she also began to enjoy her journalism in a different way. She became proud of the new Genêt, who she felt had a definite role to play in documenting history, doing so in some style and in a way far removed from traditional reportage.

In her journal over the next fifteen years, she would often succumb to further self-doubt, questioning the niche she had created for herself and wondering if her writing was too shallow (“surely the mechanical gimmick for an unfertile mind”), but during the early 1930s, she was riding high, high enough to propose to Ross that she try her hand at a London Letter as well as her regular Paris one.

For the next several months, she would travel regularly across the Channel, gathering material for several letters as well as a Profile of Queen Mary.

The path to war

Janet had always resisted returning to America, even as war appeared to be inevitable. She staunchly claimed that she would only leave when forced and that she would be “the last Middle Westerner on this peninsula of Europe.” But by September 1939 she felt her situation was untenable.

Although The New Yorker asked her to stay, she refused: almost all of her American friends had left, and the streets of Paris were emptying.

Janet had tentatively planned to leave in October for three months anyway, as her mother was not well, and she felt too guilty at leaving her sister Hildegarde with the burden of care. On October 5th, having left Paris three weeks earlier, she and Solita sailed for New York.

Letter from Paris in New York

Janet spent much of the war in America, helping to take care of her mother and continuing to write various pieces for The New Yorker. Her first, a story about the French under occupation that she researched with help from friends still in Europe, was understated, and conspicuously lacking in Genêt’s usual sarcasm and detachment.

Janet’s only nod to her previous style was to mention what was still being served at The Ritz. Her next piece, on the French Resistance, was signed with her own name, and Genêt disappeared for the next four years.

From the end of 1942 through to the beginning of 1944, Janet worked almost consistently on an extended four-part Profile of Marshal Pétain, the head of Vichy France. It was a big success — Simon & Schuster brought all four parts of the article together in book form which was published in July 1944 — and Janet herself felt that it was the best work of her career.

A tumultuous personal life

Janet’s personal life was never settled, despite the length of time she had spent with Solita and despite their devotion to each other. Both women took other partners, and in 1932 Janet had met and fallen in love with Noel Haskins Murphy, a widow who lived just outside Paris in the village of Orgeval.

It was one of her most serious affairs, and Noel would remain a lover and companion of Janet’s until the end of her life.

In New York, it happened all over again. She and Solita had set up home together just as they had done in Paris, but it wasn’t long until Janet met Natalia Danesi Murray, an Italian working at the National Broadcasting Company. After a weekend party on Fire Island, Janet was smitten, and by 1942 she had left the apartment she shared with Solita in order to sublet part of Natalia’s apartment.

Solita, however, continued to be a large part of Janet’s life (a sore point of contention between Natalia and Janet), and Janet continued to rely on her as an editor, critic, friend, and honorary member of her family. Neither did she tell Noel, now interned in a camp in the spa town of Vittel along with other American nationals, about Natalia.

Although Natalia and Noel would eventually be aware of each other, Janet consistently found herself unable to break with any of her lovers; she would often berate herself for her inability to commit fully to anything or anyone other than The New Yorker, with which all three women would have to share her.

Return to Europe

By October 1944, Janet had decided to get to France no matter what, and Jane Grant managed to get her a seat on a London-bound plane as an official army war correspondent for The New Yorker. After a terrifying flight (Janet would always hate planes) and several weeks in London, she arrived in France during the last week of November.

She was horrified at what she found. “Europe,” she wrote, “is a charnel house, filled with death, destruction, rot …” Her first letter from Paris in four years moved Ross enough that he revived the Genêt signature. In Paris, she stayed at the Hôtel Scribe, along with other foreign journalists including Hemingway.

Although she was popular and her opinions in demand, Janet was irritable and prone to outbursts. The pain she could see all around her, the waste, and the depressing atmosphere made her own loneliness and guilt worse, and she felt adrift.

Her mood was further depressed when she covered the Nuremberg Trials. She traveled throughout war-torn Eastern Europe to write letters from Warsaw, Czechoslovakia, and Austria. She was, she said, finding it harder and harder to believe in “governments, politics, religion, God, and even man himself.”

Honors and doubts

In the spring of 1948, Janet was invited to what she assumed was a social reception. She turned the invitation down, only to find out later that it had been a presentation ceremony for one of France’s highest honors, the Légion d’Honneur. For the rest of her life, she would wear the ribbon on her lapel, an acknowledgment of Genêt’s years of passionate writing.

Despite this recognition, Janet found herself reflecting — often harshly — on her writing and her life, reflections that were possibly precipitated by her mother’s death at the end of 1947. She was frustrated at becoming what she saw as a stereotypical woman: easily distracted, undisciplined once more, and passive in her work and her relationships.

While the front of Genêt was useful in that it allowed her, to some extent, to create a kind of “third sex;” Genêt was anonymous, neither male nor female, and distanced from any kind of sexual stereotype.

Janet also began to worry that Genêt also kept her removed from her own emotions and opinions, which she felt she needed to give her writing weight. It gave her a secure identity but took away her own.

At the same time, she feared striking out on her own without The New Yorker, and this seemed to paralyze her. In January 1949, she wrote in her journal:

“I have manufactured journalism for nearly a quarter of this century. Nowadays everyone manufactures. Few create. If an individual knows the difference and I do, the failure to create leaves only one conclusion: one has manufactured.”

But by then, she wrote, she believed she was too old to change.

Trouble at The New Yorker

The New Yorker saw the end of an era when Harold Ross died in December 1951, after undergoing surgery, and William Shawn took over as editor.

Janet, shocked by Ross’s death, wrote that: “I am so drowned, so hit by Ross’s death that I reach unsteadily, stiffly for words, like logs…& trying to save myself which is what all of us on the magazine feel…”

Ross, for Janet personally, had changed everything by inventing someone for her to be. “The loss of my inventor,” she said, “is more personal than the loss of my procreator, by far.”

After this upheaval, a break with the magazine nearly came in 1952 when Kay Boyle and her husband Joseph faced court as part of the McCarthy trials.

Janet offered to testify at Kay’s trial and did so wholeheartedly: she felt angry, upset, and betrayed when she discovered that, despite Kay having written for the magazine for several years, The New Yorker was lukewarm in their support. The case against both Joseph and Kay was ultimately settled in their favor, but the experience left Janet furious.

Gathering the material

During the 1950s and 1960s, Janet traveled between New York and Paris almost every other month, staying with Natalia in New York and continuing to write letters and Profiles for The New Yorker. Four of her Profiles — on Picasso, Braque, Malraux, and Matisse — were brought together in a book called Monuments and Men, published by Harper and Row in 1956.

Janet, still doubting the validity and worth of her work, was pleasantly surprised when the reviews were almost uniformly favorable. She had a further boost when, in 1958, she was given an honorary degree from Smith College.

A further collection of her work followed in 1963, when Michael Bessie (co-founder of the publishing house Atheneum) approached Janet with the idea of collecting her Paris letters into book form, to be edited and prefaced by William Shawn.

Paris Journal was published in the autumn of 1965 and reviews were generally excellent: Alan Pryce-Jones, in the New York Herald Tribune, wrote that:

“… like a conjurer, she pulls out of her hat whatever is going to divert her audience; but, unlike the conjurer’s, her rabbits are still alive after twenty years,” while the Washington Post hailed her as a “paragon of foreign correspondents — the one with a first-class brain, plus the best senses in the business.”

The book won a National Book Award in 1966, and a second volume soon followed.

Janet was less enthusiastic about a collection of her early writing: those letters from the 1920s and 1930s that she and Shawn had originally not included in Paris Journal. But she finally acquiesced under the enthusiasm of Irving Drutman at Viking.

This early work would be collected under the title Paris Was Yesterday, and to Janet’s surprise it was a critical hit: Anatole Broyard at the New York Times called it a “bouquet of epiphanies,” while George Wickes, writing in the New Republic, said it was “the work of a biographer with a touch of gallows humor and an unfailing curiosity.”

“Dying or going crazy”

By this time Janet was exhausted, both professionally and personally. Now in her seventies, the constant demands of her Paris letters and the traveling between continents were beginning to take their toll.

All of her friends were “dying or going crazy or having terrible operations,” and she feared the same for herself: her memory was failing, she suffered from kidney stones, and what had started as an irritating pain in her hand had grown so bad that she could no longer physically write.

Her memory lapses, in particular, made writing her Paris letters difficult, and friends started to wonder privately whether she wasn’t too out of touch. Increasingly she relied on others to tell her what was going on, what events were happening, and what she should focus on.

She became ill with sciatica, which made her irritable and finished off the decade with two cracked ribs and a nasty bout of food poisoning. She did, however, retain her sense of humor and her mischievous side, enjoying shocking those who thought that she would be more sedate.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Last letters

Janet’s frailty shook her confidence. Cared for by Natalia in New York, and by Noel, Solita, and Solita’s partner Lib Clark in Paris, it soon became clear that finally, at the age of eighty-three, her traveling days were over. When she left Orgeval in October 1975 it was for the last time. Solita, aged 87, died one month later.

In New York, Janet’s memory continued to worsen. She visited The New Yorker offices when she could, but she was often irritable and confused.

At a 1978 Rutgers University conference on women, the arts, and the 1920s, she appeared on a panel with several of her old friends but did not speak; it was clear that, although she was enjoying herself, she had no idea where she was. She died not long afterward, on November 7, 1978, of undetermined causes.

Legacy

Janet Flanner was an intrinsic part of the history of The New Yorker, defining a style and a generation through her Paris letters. Many of her contributions can still be read on the magazine’s website, and Paris Was Yesterday is still popular, having been reissued by Virago Modern Classics.

She is also credited as being one of the inspirations behind the 2021 film The French Dispatch. But she herself did not want to be known only as a journalist.

She was a woman who cared deeply for those around her and for her friends. After her death, Kay Boyle recalled Janet’s own words: “When I die, let it not be said that I wrote for The New Yorker for fifty years. Let it be said that once I stood by a friend.”

Further reading

- Janet Flanner on The New Yorker website

- Paris Was Yesterday, 1925-1939 by Janet Flanner (Virago Modern Classics, 2003)

- Genêt: A Biography of Janet Flanner by Brenda Wineapple (Harper Collins, 1989)

- Darlinghissima: Letters to a Friend by Janet Flanner, edited and introduced by Natalia Danesi Murray (Harvest / HBJ, 1986)

- Janet, My Mother and Me by William Murray (Simon & Schuster, 2000)

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find her online at Elodie Rose Barnes.

Leave a Reply