Inspiration from 6 Classic Caribbean Women Writers

By Lynne Weiss | On October 21, 2022 | Updated April 5, 2024 | Comments (0)

How can writers reconcile the demands of the social and political moment with the demands of their craft? Caribbean women writers of color offer some models in the way they explore the rich intersection of concerns with gender, race, and colonialism through their work.

Anglophone writers with links to African and indigenous Caribbean cultures as well as to the United States or the United Kingdom (or both) express those connections with language, story, and rhythm.

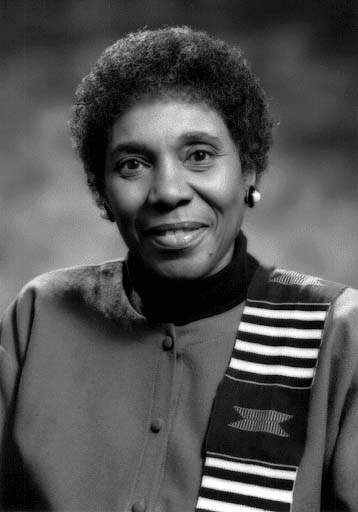

Following are brief introductions to several classic Caribbean women writers, listed in order of their dates of birth — Rosa Guy, Paule Marshall (shown above), Georgina Herrera, Michelle Cliff, Mahadai Das, and Jean “Binta” Breeze.

My thanks to Dr. Warren R. Harding, whose work focuses on Black Caribbean women writers, for introducing me to these notable women. Dr. Harding, who has a Ph.D. in Africana studies, is completing a post-doctoral fellowship at Brown University.

. . . . . . . . .

Rosa Guy:

“Only if We Care!”

Rosa Guy (September 1, 1922–June 3, 2012) was “never afraid of the truth,” Maya Angelou said upon Guy’s death. Guy (rhymes with “key”) was born in Trinidad. Orphaned at the age of fourteen, she lived for a time with a relative who was a supporter of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, an experience that led her to see herself as an Africanist and to oppose colonialism.

Guy studied acting at the American Negro Theatre in New York. She went on to cofound the Harlem Writers Guild in 1950, an organization that nurtured the work of writers such as Paule Marshall, Audre Lorde, and Maya Angelou.

Guy wrote for both adults and young adults. Her first novel, Bird at My Window, was written for adults and published in 1966. In the 1970s, she wrote a trilogy of novels for young adults. The Friends (1973), Ruby (1976), and Edith Jackson (1978), drew on her experiences as a young immigrant.

Her characters portray the tensions between Black West Indians and African Americans, same-sex relationships, and unwanted pregnancy—topics that were off-limits in YA literature at the time.

Alice Walker, reviewing The Friends for the New York Times, called the book a “heart-slammer.” Active in both traditional civil rights and Black nationalist movements, Guy was driven to share her ideas through her creative work. “The sharing of cultures—a rare and beautiful concept—is inevitable,” she wrote. “We cannot prevent change, but we can guide generational change if we care—only if we care!”

Guy’s most successful adult novel was My Love, My Love: Or, The Peasant Girl (1985), a retelling of “The Little Mermaid” set on a Caribbean island. The novel was adapted for the stage as a musical and was nominated for eight Tony Awards during its Broadway run of over a year.

. . . . . . . . .

Paule Marshall:

A Barbadian in Brooklyn

Paule Marshall (April 9, 1929–August 12, 2019) was an activist in the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s, and saw herself as a “tripartite” person, incorporating her connections to Brooklyn, Barbados, and Africa into her work. A protégé of Langston Hughes, her work was regarded by critics to be the spark that ignited contemporary Black women’s writing.

Marshall’s parents came from Barbados, and Paule, whose original name was Valenza Pauline Burke, was born in 1929 in Brooklyn, New York.

A year spent in Barbados with her grandmother when she was nine left a lasting impact, as did her discovery of the poetry of Black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Her pen name Paule (the e is silent) is a nod to Dunbar, whose work inspired her to become a writer.

Marshall’s first novel, Brown Girl, Brownstones was published in 1959. She credits the Barbadian women who gathered in her mother’s Brooklyn kitchen to exchange stories at the end of their workday, these “poets of the kitchen,” as she called them, with teaching her the foundations of her craft.

“They trained my ear. They set a standard of excellence. This is why the best of my work must be attributed to them; it stands as testimony to the rich legacy of language and culture they so freely passed on to me in the wordshop of the kitchen.”

Her 1969 novel, The Chosen Place, The Timeless People, includes characters and cultural influences of Africa, the United States, the Caribbean, China, and India. Her 1983 novel, Praisesong for the Widow, portrays the anguish of a wealthy, well-educated African American woman who experiences a spiritual reawakening while visiting a Caribbean island, and garnered Marshall the most critical attention.

In her lifetime, Marshall received a MacArthur Foundation “genius” award and was designated a Literary Lion by the New York Public Library.

- Biography of Paule Marshall on this site

- Britannica

- Emory University Scholar Blogs

- The Guardian (obituary)

- AALBC (books by Paule Marshall)

. . . . . . . . .

Georgina Herrera:

A Genuine Cuban Voice

Georgina Herrera (April 23, 1936–December 13, 2021) was an Afro-Cuban poet who was praised for her awareness of “the simultaneity of suffering and joy, the fleetingness of the terrible and the permanence of the kind.” While she wrote in Spanish, her work is known internationally and has been translated into English.

Born to a family of Nigerian descent in Matanza, Cuba, Herrera was a feminist. Her devotion to elevating older Black women’s stories in Cuban society led many to consider her one of Cuba’s most genuine voices.

Forced to leave school when she was in eighth grade, Herrera fled to Havana in 1956, when she was 20. She worked at first as a house cleaner and published her first collection of poetry, GH, in 1962. She then took a position with a Havana radio station where she wrote short stories, plays, and radio dramas.

In the early 1960s, her poetry and her associations with other outspoken writers led to her marginalization. But she continued writing, and ultimately published nine books of poetry that have been translated into several languages.

Her 2016 volume, Always Rebellious/ Cimarroneando, won the 2016 International Latino Book Award for Best Bilingual Poetry Book. Her poem “Africa” from that volume expresses her determination to claim her African identity within her Caribbean context:

Whenever I mention you

or whenever you are named in my presence,

it will be to praise you.

I care for you.

At your side I remain, as at the foot of

the tallest tree.

I think

of the water in your rivers, and my eyes

remain moist.

. . . . . . . . .

Michelle Cliff:

Claiming Multiple Identities

Michelle Cliff (November 2, 1946–June 12, 2016) wrote that the aim of her work was “to reject speechlessness … to invent my own particular speech with which to describe my own peculiar self, to draw together everything I am and have been.”

Cliff’s “own peculiar self” embodied complexities: she was a light-skinned Black lesbian born in Jamaica, raised in both Jamaica and a West Indian neighborhood in New York City, who studied in London and the United States.

In 1975, while working for W. W. Norton as a production editor for books on women’s studies, she met poet Adrienne Rich. The two became partners and remained so throughout their lives.

Cliff’s first book, Claiming an Identity They Taught Me to Despise, was a series of prose poems published in 1980. Her first novel, Abeng, was published in 1984 and portrays a relationship between a light-skinned Jamaican girl and a darker girl from an impoverished family.

Subsequently, Cliff published No Telephone to Heaven (1987), a novel that portrays characters in Jamaica, New York, and London: Free Enterprise: A Novel of Mary Ellen Pleasant (1993), about a Jamaican woman who worked with Pleasant, the first African American millionaire, to help finance John Brown’s 1859 raid; and the essay collection, If I Could Write This in Fire (2008), described as the “emotionally urgent” expression of “a radical, powerful, and essential artist.”

- Poetry Foundation

- NY Times (obituary)

- Poetry Foundation (obituary)

- Emory University Scholar Blogs

- If I Could Write in this Fire

. . . . . . . . .

Mahadai Das:

A Poet of Her People

Mahadai Das (October 22, 1954–April 3, 2003) was a descendant of indentured Indian laborers. Born in Guyana, a nation on the Caribbean coast of South America, Das received a B.A. at Columbia University. Her work in a doctoral program at the University of Chicago was cut short after she fell ill.

Politically active at a time when it was dangerous to be so in Guyana, Das brought passion and wit to her work as well as a willingness to risk everything for her beliefs and her craft. She refused to use a pen name, even though the government of her country was actively prosecuting—and killing—its opponents.

Das, whose first collection of poetry was titled I Want to Be a Poetess of My People, was one of the first Indo-Caribbean women to publish her work.

In the poems in that book as well as in her subsequent volume, A Leaf in His Ear, she explores the discrimination faced by those of the Indian diaspora, her Indian heritage, and the discrimination she faced as a woman, even from men with whom she shared that heritage and identity. A powerful brief poem, untitled, illustrates the authority of her voice:

Look at me:

when you speak,

mountain ranges

rise inside me.

. . . . . . . . .

Jean “Binta” Breeze:

Bringing the Rhythms of Reggae to Poetry

Jean “Binta” Breeze (March 11, 1956–August 4, 2021), the Jamaican poet, was often referred to as “a one-woman festival” for her powerful poetry performances.

Recognized as the first woman to make a name for herself in the male-dominated field of dub poetry—an art form that combines the rhythms of reggae music with poetry performance—Jean “Binta” Breeze used a wide range of subjects and styles to encapsulate the experiences of Black women.

Born and raised in rural Jamaica, Breeze took the African name “Binta,” which she was told meant “close to the heart,” while living in a Rastafarian community. In 1985, she was invited to perform at the International Book Fair of Radical Black and Third World Books in the UK.

She returned to London soon after to teach theater studies. Within a couple of years, she was able to leave teaching to focus on writing. She was influenced by the British feminist movement of the 1990s, but she was always clear that she wrote “for the Caribbean and the third world.”

“I want to make words/music/move beyond language/into sound,” she wrote. In later years, she divided her time between England and Jamaica.

She published several books of poetry, including Third World Girl, which includes poems selected from Riddym Ravings, Spring Cleaning, On the Edge of an Island, and The Arrival of Brighteye.

She also released five albums, and you can hear recordings of her readings at Poetry Archive. She wrote scripts for theater and film, and her poem “dreamer” was posted in the London Underground as part of a celebration of Caribbean poetry. She became a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in recognition of her services to literature.

Contributed by Lynne Weiss: Lynne’s writing has appeared in Black Warrior Review; Brain, Child; The Common OnLine; the Ploughshares blog; the [PANK] blog; Wild Musette; Main Street Rag; and Radcliffe Magazine. She received an MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and has won grants and residency awards from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the Millay Colony, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She loves history, theater, and literature, and for many years, has earned her living by developing history and social studies materials for educational publishers. She lives outside Boston, where she is working on a novel set in Cornwall and London in the early 1930s. You can see more of her work at LynneWeiss.

Leave a Reply