Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Scandinavia (1796)

By N.J. Mastro | On March 10, 2025 | Updated April 27, 2025 | Comments (4)

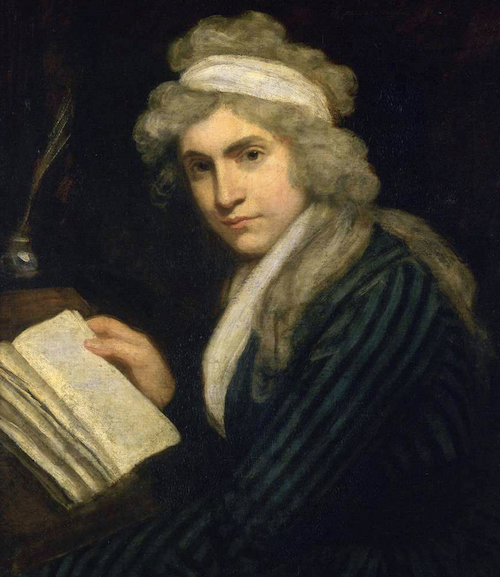

The work of feminist writer and philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft’s (1759–1797) has endured, despite attempts of critics of her time to bury her legacy after her death. A year after she died, her husband, William Godwin, published Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman, unwittingly turning the public against the love of his life.

Two generations later, however, women rediscovered Mary Wollstonecraft’s writing — breathing new life into a historical figure who might have been forgotten along with other notable women whose words were lost to the patriarchy.

William Godwin meant no harm when he published his memoir of Mary Wollstonecraft in 1798. Mired in grief, he wanted the world to know Mary the way he did— as a compassionate, brilliant woman.

His mistake was putting her personal life on display by including her private letters to her former lover, Gilbert Imlay, an American businessman, in the appendix of the memoir. Mary had lived with Imlay and had their daughter, Fanny, out of wedlock. The public scorned Mary, judging her to be immoral. The public turned on Godwin as well; his stature in the literary and political establishment plummeted.

What could he have been thinking? If Godwin wanted people to know the real Mary Wollstonecraft, he could have simply directed them to her 1796 travel narrative: Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark is a highly personal account of Mary’s journey to Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. She traveled to these Scandinavian countries in 1795 on Gilbert Imlay’s behalf, hoping to recover a missing shipment of silver.

Mary’s ultimate goal: to win Imlay back from the actress he had taken up with. Bereft over his infidelity, she tried to take her own life by drinking laudanum.

. . . . . . . . .

Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft by N.J. Mastro

is available on Bookshop.org*, Amazon*, and wherever books are sold

. . . . . . . . .

Mary met Gilbert Imlay in France in 1793, where she had moved to write about the French Revolution. Imlay, an American, was there on “business.” Perhaps seeing an independent, adventuresome spirit akin to her own (they both resisted the idea of marriage), they embarked on an affair.

After a time, Imlay pulled away from Mary. When he moved to London for his shipping enterprise and left her in Paris with their child, Mary plunged into an emotional abyss. A few months later, when France declared war on Great Britain, she was in danger. As a British national, the authorities could arrest her at any moment. Making matters worse, her once revolutionary writing had suddenly marked her as an anti-revolutionary under Maximilien Robespierre’s new regime. To be on the safe side, she and Imlay pretended to be married. Her status as his wife, Imlay assured her, would ward off the authorities.

Mary didn’t foresee the trap she was stepping into — the kind that ensnares women who are blinded by love. When she and Imlay faked their marriage certificate with the help of the American ambassador, Gouverneur Morris, they never spoke of how the lie might end. Imlay’s sudden abandonment of Mary and their daughter forced the question.

Persistent and determined, Mary knew her reputation (and thus her livelihood) would be ruined if it were to come out that she and Imlay weren’t married. Thus, in the spring of 1795, she would have done anything to keep him. That included traveling to Scandinavia to find the shipment of missing silver — which, to Mary’s horror, Imlay had stolen.

It was audacious to travel alone to Scandinavia with only her daughter Fanny and the child’s nursemaid as companions. Scandinavia was a remote, rugged land in the far northern reaches of the hemisphere. Mary hired no guide and carried no pistol for protection. She wrote frequently to Imlay, expressing the intense sadness she felt:

“How am I altered by disappointment! — When going to [Lisbon] ten years ago, the elasticity of my mind was sufficient to ward off weariness — and the imagination could dip her brush in the rainbow of fancy, and sketch futurity in smiling colours. Now I am going towards the North in search of sunbeams! — Will any ever warm this desolated heart? All nature seems to frown — or rather mourn with me. — Every thing is cold — cold as my expectations! … I have lost the little appetite I had; and I lie awake, till thinking almost drives me to the brink of madness — only to the brink for I never forget, even in the feverish slumbers I sometimes fall into, the misery I am labouring to blunt …”

In addition to documenting the journey in letters, Mary kept notes of her travels. Prior to leaving London, she had secured an advance from her publisher, Joseph Johnson, for a travel narrative to be written upon her return.

. . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Mary Wollstonecraft

. . . . . . . . .

Mary’s mission to recover Imlay’s silver fell short, but not before turning over every possible lead in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark — all to no avail. Upon her return to London, she and Imlay parted for good. Distraught, Mary attempted to drown herself by jumping into the Thames. Watermen rescued her downstream.

As she had always done, Mary turned to her pen as an antidote to despair. During her physical and emotional recovery, she realized that the letters she’d written to Imlay (which he had returned to her) were the perfect the framework for her travel narrative. In a matter of months, she penned Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, an epistolary travel narrative addressed to an unnamed individual.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an Enlightenment philosopher Mary favored, may have influenced the structure of her travel narrative. Rousseau’s Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782), an autobiographical account of his walks in France in the final years of his life, revealed his state of disenchantment. Mary likely felt some affinity with Rousseau as she traveled alone with her daughter in the verdant taiga in the summer of 1795.

Mary had been more discrete than her future husband William Godwin, who put her words before a harsh public after her death. For example, she wrote to Imlay that summer from Gothenburg, Sweden, on July 1:

“I labor in vain to calm my mind — my soul has been overpowered by sorrow and disappointment. Every thing fatigues me — this is a life that cannot last long … we must either resolve to live together, or part for ever, I cannot bear these continual struggles.”

But in her travel narrative, she tempered her expression, pulling a thin veil over her distressed feelings, yet baring her soul as she confessed how sadness enveloped her in this foreign land:

“How frequently has melancholy and even misanthropy taken possession of me, when the world has disgusted me, and friends have proved unkind.”

Mary admitted that she carried deep wounds — a daring move for a writer, especially a woman. In a later passage in Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, she became more direct:

“You have sometimes wondered, my dear friend, at the extreme affection of my nature. But such is the temperature of my soul. It is not the vivacity of you, the heyday of existence. For years I have endeavoured to calm an impetuous tide, labouring to make my feelings take an orderly course. It was striving against the stream. I must love and admire with warmth, or I sink into sadness. Tokens of love which I have received have wrapped me in Elysium, purifying the heart they enchanted.”

Who is “you?” Mary doesn’t tell the reader, but those in her circle knew she was writing to Imlay, whom they also believed was her husband. Mary didn’t care. Using Imlay as a prop to tell her story, projecting him as cold and unfeeling, she gave herself the last word in their failed love affair.

Scandinavia wasn’t a complete loss for Mary. Her travel narrative conveyed how time spent in nature improved her lagging spirits, and she seemed to have gotten a modicum of relief from her melancholy. Glimmers of the Mary of old began to resurface, and she charmed readers with frankness and sincerity.

So smitten was William Godwin upon reading Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, he remarked, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book.” He and Mary first met at a dinner held by her publisher, Joseph Johnson, where they traded fiery words. Four years later, they reconnected. In Memoirs, Godwin described their renewed acquaintance:

“When we met again, we met with new pleasure, and, I may add, with a more decisive preference for each other … It was friendship melting into love. Previously to our mutual declaration, each felt half-assured, yet each felt a certain trembling anxiety to have assurance complete.”

In Memoirs, Godwin adopted some of Mary’s candor, writing that he’d never loved a woman until he met her. Godwin was a confirmed bachelor who avoided marriage. Mary did as well, so they were, in that sense, a perfect match … that is, until she became pregnant. With Imlay back in France, she had a decision to make. Knowing that she’d be ostracized if it were to come out that she and Imlay had never been wed, she married Godwin. For with him, she’d finally found a union of love based on mutual respect and adoration.

The Godwins delighted in redefining the institution of marriage and did things their way. People who are ahead of their time, Mary asserted, must be willing to face censure; yet surprisingly, they got away with most of their bold actions.

William Godwin woefully miscalculated the public’s reaction when he paid tribute to Mary Wollstonecraft upon her death. His revelations resulted in the very damage to her reputation she had managed to circumvent during her unorthodox life.

. . . . . . . . . .

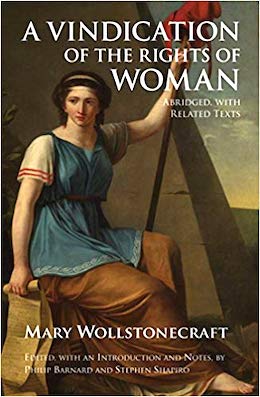

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: An Appreciation

. . . . . . . . . .

As the 19th century unfolded, suffragists in America and Great Britain resurrected Mary Wollstonecraft’s writings. They turned to A Vindication of the Rights of Woman for inspiration in their quest to secure equal rights. For these reformers, it wasn’t just about the vote; they wanted educational equality, the opportunity to work in any chosen occupation, and the ability to enter the political sphere. In short, they wanted agency and freedom.

“I do not wish them [women] to have power over men;” Mary wrote in her now-famous treatise, “but over themselves.”

Today, historians widely refer to Mary Wollstonecraft as the mother of feminism. William Godwin holds the distinction of being known as the founder of philosophical anarchism, a political philosophy that promotes self-government and progressive rationalism, including benevolence to others. Both are tremendous gifts to humanity.

Another was the child born to William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary Godwin grew up to be Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein or, The Modern Prometheus, the 1818 novel that launched the genre of science fiction. Mary Shelley never knew her mother, but clearly, Mary Wollstonecraft’s revolutionary spirit resided in her.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by N.J. Mastro, the author of Solitary Walker: A Novel of Mary Wollstonecraft, a biographical novel about Mary Wollstonecraft’s incredible rise as a writer and philosopher and her ill-fated forays into love. Set against the backdrop of 18th-century London, the French Revolution, and the remote shores of Scandinavia, this well-researched novel captures the timeless story of a woman in search of herself.

*These are Bookshop.org and Amazon affiliate links. If a product is purchased after linking through, Literary Ladies Guide receives a modest commission, which helps us to keep growing.

Thank you for this insightful and beautifully written piece on Mary Wollstonecraft’s, “Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark.”

It captures her resilience, emotional depth, and pioneering spirit with such care.

The exploration of her journey—both literal and emotional—offers a poignant glimpse into her humanity and brilliance – it s a fitting tribute to a woman whose words, like her daughter’s, continue to inspire across generations.

And thank you so much for your kind and generous comment, Kelly. Kudos to NJ Mastro, who contributed this article.

You’re very welcome and I am a very big fan, I have both your book and audiobook (Literary Ladies). Thank you!

How lovely, thank you!