Frankenstein by Mary Shelley: A Synopsis and View from the 19th Century

By Taylor Jasmine | On March 3, 2018 | Updated January 1, 2025 | Comments (0)

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851) is the British author, is best known for the 1818 classic, Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus. In the summer of 1814, seventeen-year-old Mary ran off to Europe with the married poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

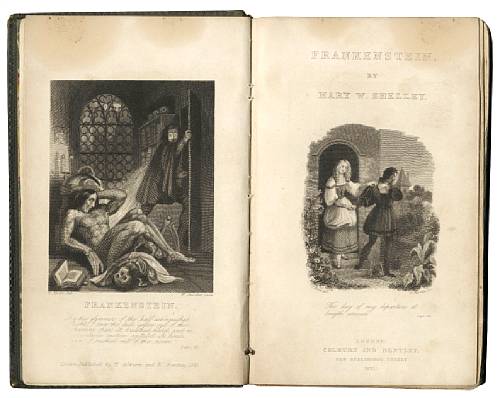

There she joined his literary circle, which included Lord Byron. The events that inspired the creation of the tale took place during the couple’s sojourn in Italy. It was published in 1818, when Mary was barely 21 years old.

Read in Mary Shelley’s own words how she came to write one of the most haunting tales of all time.

A detailed synopsis of Frankenstein, this excerpt, adapted from Mrs. Shelley (1890) by Lucy Madox Brown Rossetti, provides an excellent outline of the plot, with a late 19th-century perspective:

A detailed synopsis of the plot of Frankenstein

That a work by a girl of nineteen should have held its place in romantic literature so long is no small tribute to its merit; this work, wrought under the influence of Lord Byron and Percy Shelley, and conceived after drinking in their enthralling conversation, is not unworthy of its origin.

The story of Frankenstein begins with a series of letters of a young man, Robert Walton, writing to his sister, Mrs. Saville in England, from St. Petersburg, where he is about to embark on a voyage in search of the North Pole. He is bent on discovering the secret of the magnet, and is deluded with the hope of a never absent sun.

Encountering a gigantic being

When advanced some distance towards his longed-for goal, Walton writes of a most strange adventure which befalls them in the midst of the ice regions—a gigantic being, of human shape, being drawn over the ice in a sledge by dogs.

Not many hours after this strange sight a fresh discovery was made of another man in another sledge, with only one living dog to it: this time the man was seen to be a European, whom the sailors tried to persuade to enter their ship.

A skeletal and bedraggled stranger

On seeing Walton, the stranger, speaking English, asked whither they were bound before he would consent to enter the ship. This naturally caused intense excitement, as the man, reduced to a skeleton, seemed to have but a short time to live.

However, on hearing that the vessel was bound northwards, he consented to enter, and with great care he was restored for the time. In answer to an inquiry as to his object … he replied, “To seek one who fled from me.”

An affection springs up and increases between Walton and the stranger, till the latter promises to tell his sad and strange story, which he had hitherto intended should die with him.

. . . . . . . . . . .

See also: How Mary Shelley Came to Write Frankenstein (1818)

. . . . . . . . . . .

The story told by the dying man

This commencement leads to the story being told in the form of a long narrative by the dying man, whose name is Victor Frankenstein. The stranger describes himself as of a Genovese family of high distinction, and gives an interesting account of his father and juvenile surroundings, including a playfellow, Elizabeth Lavenga, whom we encounter much later in his history.

All his studies are pursued with zest, till coming upon the works of Cornelius Agrippa he is led with enthusiasm into the ideas of experimental philosophy; a passing remark of “trash” from his father, who does not explain the difference between past and modern science, is not enough to deter him and prevent the fatal consequence of the study he persists in, and thus a pupil of Albertus Magnus appears in the eighteenth century.

The effects of a thunderstorm, described from those Mary had recently witnessed, decided him in his resolution, for electricity now was the aim of his research.

After having passed his youth in a happy Swiss home with his parents and dear friends, on the death of his loved mother he starts for the University of Ingolstadt.

Here he is rebuked by the professors for his useless studies, until one, Mr. Waldeman, sympathises with him, and explains how Cornelius Agrippa and others, although their studies did not bring the immediate fruit they expected, nevertheless helped on science in other directions, and he advises Frankenstein to pursue his studies in natural philosophy, including mathematics.

Discovering the principle of life

The upshot of this advice is that two years are spent in intense study and thought. He is contemplating a visit to his home, when, making some fresh experiment, he finds that he has discovered the principle of life; this so overcomes him for a time that, oblivious of all else, he is bent on making use of his discovery.

He determines to create a being superior to man, so that future generations shall bless him.

In the first place, by the help of chemistry, he has to construct the form which is to be animated. A grave has to be ransacked in the attempt, and Frankenstein describes with loathing some of the details of his work, and shows the danger of overstraining the mind in any one direction—how the virtuous become vicious, and how virtue itself, carried to excess, lapses into vice.

The form is created in nervous fear and fever. Frankenstein being the ideal scientist, devoid of all feeling for art, without any ideal of proportion or beauty, reaches the point where he considers nothing but the infusion of life necessary. All is ready, and in the first hour of the morning he applies his fatal discovery.

The monster is animated

Breath is given, the limbs move, the eyes open, and the colossal being or monster, as he is henceforth called, becomes animated; though copied from statues, its fearful size, its terrible complexion and drawn skin, scarcely concealing arteries and muscles beneath, add to the horror of the expression.

Overwhelmed by disgust, his creator can only rush from the room, and finally falls exhausted on his bed, only to wake to find his monster grinning at him. [editor’s note: keep in mind that Victor Frankenstein is the scientist; we’ve come to call the monster by the name Frankenstein, but he’s technically Frankenstein’s monster or creature]

Frankenstein hurries on, but coming across his old friend Henri Clerval at the stage coach, he recalls to mind his father, Elizabeth, his former life and friends.

He returns to his rooms with his friend. Reaching his door, he trembles, but opening it, finds himself delivered from his self-created fiend. His frenzy of delight being attributed to madness from overwork, Clerval induces Frankenstein to leave his studies, and, finally (after he had for months endured a terrible illness), to accompany him to his native village.

Mysterious death of Victor Frankenstein’s young brother

Various delays occurring, they are detained too late in the year to pass the dangerous roads on their way home. Health and peace of mind returning to some decree, Frankenstein is about to proceed on his journey homewards, when a letter arrives from his father with the fatal news of the mysterious death of his young brother.

This event hastens still further his return, and gives a renewed gloomy turn to his mind; not only is his loved little brother dead, but the extraordinary event points to some unknown power.

From this time Frankenstein’s life is agony. One after another, all whom he loves fall victims to the demon he has created; he is never safe from his presence; in a storm on the Alps he encounters him; in the fearful murders which annihilate his family he always recognizes his hand.

The monster seeks a truce

On one occasion his creation wished to have a truce and to come to terms with his creator. This, after his most fearful treachery had caused the innocent to be sentenced as the perpetrator of his fearful deeds.

On meeting Frankenstein he recounts the most pathetic story of his falling away from sympathy with humanity: how, after saving the life of a girl from drowning, he is shot by a young man who rushes up and rescues her from him.

He became the unknown benefactor of a family for some period of time by doing the hard work of the household while they slept.

Having taking refuge in a hovel adjoining a corner of their cottage, he hears their pathetic and romantic story, and also learns the language and ways of men; but on his wishing to make their acquaintance the family are so horrified at his appearance that the women faint, the men drive him off with blows, and the whole family leave a neighborhood, the scene of such an apparition.

After these experiences he retaliates, till meeting Frankenstein he proposes these terms: that Frankenstein shall create another being as repulsive as himself to be his companion—in fact, he desires a wife as hideous as he is. These were the conditions, and the lives of all those whom Frankenstein held most dear were in the balance; he hesitated long, but finally consented.

. . . . . . . . . . .

You might also like:

Quotes from Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

. . . . . . . . . . .

For the love of Elizabeth

Everything now had to be put aside to carry out this fearful task — his love of Elizabeth, his father’s entreaties that he should marry her, his hopes, his ambitions, go for nothing.

To save those who remain, he must devote himself to his work. To carry out his aim he expresses a wish to visit England, and, with his friend Clerval, descends the Rhine.

After passing London and Oxford and various places of interest, he expresses a desire to be left for a time in solitude, and selects a remote island of the Orkneys, where an uninhabited hut answers the purpose of his laboratory. Here he works unmolested till his fearful task is nearly accomplished, when a fear and loathing possess his soul at the possible result of this second achievement.

A companion for the creature?

Although the demon already created has sworn to abandon the haunts of man and to live in a desert country with his mate, what hold will there be over this second being with an individuality and will of its own?

What might be the future consequences to humanity of the existence of such monsters? He forms a resolution to abandon his dreaded work, and at that moment it is confirmed by the sight of his monster grinning at him through the window of the hut in the moonlight.

The loss of a friend, a wife, a father

Not a moment is lost. He tears his just completed work limb from limb. The monster disappears in rage, only to return to threaten eternal revenge on him and his; but the time of weakness is passed; better encounter any evils that may be in store, even for those he loves, than leave a curse to humanity.

From that time there is no truce. Clerval is murdered and Frankenstein is seized as the murderer, but respited for worse fate; he is married to Elizabeth, and she is strangled within a few hours.

When goaded to the verge of madness by all these events, and seeing his beloved father reduced to imbecility through their misfortunes, he can make no one believe his self-accusing story; and if they did, what would it avail to pursue a being who could scale the Alps, live among glaciers, and pass unfathomable seas?

Self-imposed torture

Only in sleep and dreams did Frankenstein find forgetfulness of his self-imposed torture, for he lived again with those he had loved; he endured life in his pursuit by imagining his waking hours to be a horrible dream and longing for the night, when sleep should bring him life.

When hopes of meeting his demon failed, some fresh trace would appear to lead him on through habited and uninhabited countries; he tracks him to the verge of the eternal ice, and even there procures a sledge from the wretched and horrified inhabitants of the last dwelling-place of men to pursue the monster, who, on a similar vehicle, had departed, to their delight.

The fatal scientific secret

Onwards, over the eternal ice they pass, the pursued and the pursuer, till consciousness is nearly lost, and Frankenstein is rescued by those to whom he now narrates his history; all except his fatal scientific secret, which is to die with him shortly, for the end cannot be far off.

The story is told; and the friend — for he feels the utmost sympathy with the tortures of Frankenstein — can only attempt to soothe his last days or hours, for he, too, feels the end must be near; but at this crisis in Frankenstein’s existence the expedition cannot proceed northward, for the crew mutiny to return.

Final battle with the monster

Frankenstein determines to proceed alone; but his strength is ebbing, and Walton foresees his early death. But this is not to pass quietly, for the demon is in no mood that his creator should escape unmolested from his grasp.

Now the time is ripe, and, during a momentary absence, Walton is startled by fearful sounds, and then, in the cabin of his dying friend, a sight to appall the bravest; for the fiend is having the death struggle with him — then all is over.

Some last speeches of the demon to Walton are explanatory of his deed, and of his present intention of self-immolation, as he has now slaked his thirst to wreak vengeance for his existence. Then he disappears over the ice to accomplish this last task.

Surely there is enough weird imagination for the subject. Mary Shelley didn’t merely intend to depict the horror of such a monster, but evidently wished also to show what a being, with no naturally bad propensities, might sink to when under the influence of a false position.

Some weak points and incongruities

Some weak points, some incongruities, it would be unreasonable not to expect. Mary Shelley’s facility in writing was great, and having visited some of the most interesting places in the world, with some of the most interesting people, she is saved from the dreary dulness of the dull.

Her ideas, also, though sometimes affected, are genuine, not the outcome of some fashionable foible to please a passing faith or superstition.

The last passage in the book is perhaps the weakest. It is scarcely the climax, but an anticlimax. The end of Frankenstein is well conceived, but that of the Demon fails. It is ridiculous to conceive anyone, demon or human, having ended his vengeance, fleeing over the ice to burn himself on a funeral pyre where no fuel could be found.

Surely the tortures of the lowest pit of Dante’s Inferno might have sufficed for the occasion.

— adapted from Mrs. Shelley (1890) by Lucy Madox Brown Rossetti, Chapter VII, “Frankenstein”

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- Wikipedia

- Reader discussion on Goodreads

- Full text on Project Gutenberg

- The Science of Life and Death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

- How Frankenstein’s Monster Became Human

Leave a Reply