Cassandra Mortmain: Coming of Age in I Capture the Castle

By Francis Booth | On April 23, 2023 | Updated August 13, 2023 | Comments (0)

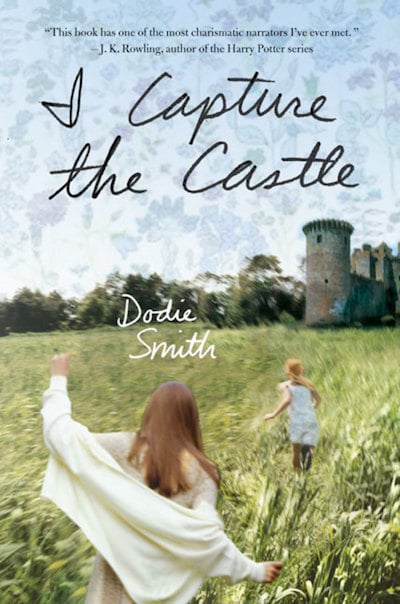

Presented here is a deep dive into the character of Cassandra Mortmain, the heroine of Dodie Smith’s 1948 young adult novel, I Capture the Castle.

British writer Dodie Smith (1896 – 1990) is best known for the children’s book The 101 Dalmatians (1956). I Capture the Castle (1948), written after World War II while Smith was living in California and writing scripts for the movies, was her first novel.

The following is excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid 20th-Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

In the female Bildungsroman tradition

I Capture the Castle is very much in the female bildungsroman tradition; though it concerns a teenage girl it is oriented at an adult, literary audience.

It foreshadows many of the characteristics of Shirley Jackson’s novels and central characters: the spooky house acting as almost a character in the novel (The Sundial; The Haunting of Hill House; We Have Always Lived in the Castle — even Jackson’s title here is very similar to Smith’s).

In Greek mythology, Cassandra was cursed to utter predictions that were true but which no one would believe, and in real life, Cassandra was Jane Austen’s elder sister, so Cassandra Mortmain’s name has multiple resonances.

The Mortain’s genteel poverty and oddball father

Cassandra’s castle, unlike Mary Katherine’s in We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a real one: literary rather than metaphorically Gothic. Medieval, literally crumbling, unheatable, and virtually uninhabitable, the Mortmain family inhabits the parts of it which still have some vestiges of a roof in virtually total poverty.

The family lives in a genteel poverty — intellectual, and eccentric – in a very English sense. The castle, which they rent on a forty-year lease, was at one time superbly furnished but all the furniture has been sold to raise money.

Unlike Shirley Jackson’s Hill House, the castle is not literally haunted: “There are said to be ghosts – which there are not. (There are some queer things up on the mound, but they never come into the house.)”

Cassandra’s father is a writer and had some years earlier published the avant-garde book Jacob Wrestling (a reference to Kierkegaard) to great critical acclaim though to no great sales.

There is virtually no revenue from the book anymore and he has now stopped writing altogether following a short stay in prison as a result of a dispute with a neighbor. He now spends most of his time locked away in a study, apparently doing puzzles.

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom is available on Amazon US and Amazon UK

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Introducing Cassandra, Thomas, & Stephen

The narrator is shy, bookish Cassandra – “I am seventeen, look younger, feel older. I am no beauty but have a neatish face.”

Along with her father, the household includes Cassandra’s more outgoing older sister, Rose – “nearly 21 and very bitter with life,” their younger brother Thomas and their father’s young but rather ghostlike wife Topaz.

If anyone is haunting the castle it is Topaz, a very fey character who likes to stride around the estate naked under her raincoat and play Greensleeves on the lute upstairs – not that she is exactly the madwoman in the attic; she is too fashionable for that.

Cassandra says she is “tall and pale, like a slightly dead goddess.” It is not at all clear why she stays in the dilapidated castle but she genuinely seems to love Cassandra’s father and gets on well with his daughters.

Unlike Cassandra, the younger brother Thomas attends school. “I rather miss school itself – it was a surprisingly good one for such a quiet little country town. I had a scholarship, just as Thomas has at his school; we are tolerably bright.”

There is another male character in the household who is not part of the family: Stephen, whose mother was the maid to the family and who now lives with them; he is infatuated with Cassandra but not vice versa.

Stephen writes poetry to Cassandra, or rather he copies classic poems and pretends he has written them himself. Literary Cassandra of course recognizes them but says nothing to avoid hurting Stephen’s feelings. The household is completed by two dogs, Abelard and Heloïse.

. . . . . . . . .

A 1948 review of I Capture the Castle

. . . . . . . . .

Our heroine is an aspiring writer

Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle is famous for its first paragraph, but I Capture the Castle can match it for grabbing our attention.

“I write this sitting in the kitchen sink. That is, my feet are in it; the rest of me is on the draining-board, which I have padded with our dogs’ blanket and the tea-cosy. I can’t say that I am really comfortable, and there is a depressing smell of carbolic soap, but this is the only part of the kitchen where there is any daylight left. And I have found that sitting in a place where you have never sat before can be inspiring – I wrote my very best poem while sitting on the hen-house.”

Cassandra keeps a journal and aims to write a novel. “I am writing this journal partly to practice my newly acquired speed-writing and partly to teach myself how to write a novel.”

Cassandra’s father critiques her writing, without much sympathy or enthusiasm. “The only time Father obliged me by reading one of them, he said I combined stateliness with a desperate effort to be funny. He told me to relax and let the words flow out of me.”

Exalted literary foremothers

The only way out of their poverty appears to be Rose making a good marriage, but this seems to be impossible; we are not in Jane Austen territory, though at one point Rose enviously mentions Pride and Prejudice to Cassandra.

“How I wish I lived in a Jane Austen novel!”

I said I’d rather be in a Charlotte Brontë.

“Which would be nicest – Jane with a touch of Charlotte, or Charlotte with a touch of Jane?”

This is the kind of discussion I like very much but I wanted to get on with my journal, so I just said: “Fifty percent each way would be perfect,’ and started to write determinedly.

Later, though, Cassandra veers back to Austen, after whose sister she is named:

“I don’t intend to let myself become the kind of author who can only work in seclusion – after all, Jane Austen wrote in the sitting room and merely covered up her work when a visitor called (though I bet she thought a thing or two) – but I am not quite Jane Austen yet and there are limits to what I can stand.”

The village vicar, apparently highly literary, tells Cassandra that she is “the insidious type – Jane Eyre with a touch of Becky Sharp [from Vanity Fair]. A thoroughly dangerous girl.”

Like many midcentury literary heroines, Cassandra is more Amelia “Emmy” Sedley of Vanity Fair than she is like Becky Sharp. But calling an adolescent would-be novelist a dangerous girl is exactly what the novelist St. Quentin did to Portia Quayne in Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart.

Later in the novel, Cassandra is tempted to take confession with the vicar, “as Lucy Snowe did in Villette,” she says – reverting from Austen to Charlotte Brontë – though the vicar is not “High Church enough for confessions.”

Rose considers selling herself

As the extreme poverty wears them all down, Rose at one point tells Cassandra and Topaz she is considering a radical way to earn money, using her looks but without being married. “It may interest you both to know that for some time now, I’ve been considering selling myself. If necessary, I shall go on the streets.”

Cassandra points out that she cannot go street walking in the “depths of Suffolk.” Rose asks Topaz to lend her the fare to London, but Topaz tells her to continue looking for a wealthy man to marry.

This is one of many knowing asides that Dodie Smith indulges in via her narrator; she obviously loves and identifies with Cassandra, as will many readers. Smith makes sure that Cassandra is undefeated by her circumstances; chapter one ends:

“I finish this entry sitting on the stairs. I think it worthy of note that I never felt happier in my life – despite sorrowful Father, pity for Rose, embarrassment about Stephen’s poetry and no justification for hope as regards our family’s general outlook. Perhaps it is because I have satisfied my creative urge; or it may be due to the thought of eggs for tea.”

Two young single men arrive on the scene

But then, a potential savior arrives: the owner of the large house next door from whom the Mortmains lease the castle has died and the house has passed to the Fox-Cottons, a family who include two young single men from America, both of marriageable age and attractive, though one of them has a beard which all three women consider unacceptable.

Worse, this is Simon, the actual heir to the estate and the most marriageable of them all. Nevertheless, despite the beard, Rose decides she must marry Simon. Cassandra will have no part in talk of marriage; she says that she would “approach matrimony as cheerfully as I would the tomb and I cannot feel that I should give satisfaction.”

It is the physical side of marriage, of which she has no personal experience, that revolts Cassandra.

Nevertheless, despite their aversion to physical contact with men and her constant fighting off of the attentions of Stephen, Cassandra does become attracted to Simon, unlike Rose, who, although she has agreed to marry Simon, does not love him; something of a Jane Austen situation.

. . . . . . . . .

Quotes from I Capture the Castle

. . . . . . . . .

To marry or not to marry?

The turning point comes when the sisters and Topaz are looking at old paintings in the Fox-Cottons’ grand house with the brothers’ father and mother, Aubrey and Led.

Cassandra briefly considers whether she should marry Simon’s brother, Neil, and like Rose, have a thousand pounds spent on her trousseau with furs and jewelry to match, “everything we can possibly want and, presumably, lots of the handsomest children. It’s going to be ‘happy ever after,’ just like the fairy tales.”

But, she decides, it wouldn’t be so happy, and not just because of the physical side. What Cassandra resists is “the settled feeling, with nothing but happiness to look forward to.” She realizes what has been happening: Rose has come of age without her.

“I suddenly know what has been the matter with me all week. Heavens, I’m not envying Rose, I’m missing her! Not missing her because she is away now – though I have been a little bit lonely – but missing the Rose who has gone away forever.”

In Rose’s absence, Simon has turned his attention to Cassandra. “You are far prettier than any girl so intelligent has a right to be,” he says to her, sounding “fairly surprised.”

Cassandra tells him she’s prettier when Rose is not around. They dance to gramophone records – a luxury Cassandra has never experienced before, and he kisses her.

The Cinderella aspect of the story has long been apparent, as it is in many female coming-of-age novels, though neither the stepmother nor the sister are horrible to Cassandra and there are two princes here – enough to go around if things are to work out in Jane Austen fashion.

The tipping point comes perhaps when Rose overhears Simon and his mother talking about Proust; she has never heard of Proust. Later, Cassandra asks Simon if she should read Proust too.

Apparently, that was more amusing than it was intelligent because it made him laugh. “Why wouldn’t say it was a duty,” he said, “but you could have a shot at it. I’ll send you Swann’s Way.”

Simon has now started to see Cassandra as an adult, partly because of the new dress she is wearing – another Cinderella reference perhaps. “I don’t know that I approve of you growing up. Oh, I shall get used to it,” he says, “but you are perfect as you were.”

Cassandra realizes that it was “the funny little girl that he had liked – the comic child playing at Midsummer nights; she was the one he kissed.” He preferred her before she began to come of age.

Cassandra does not marry Simon; she realizes that “when he nearly asked me to marry him it was only an impulse – just as it was when he kissed me on Midsummer Eve; a mixture of liking me very much and longing for Rose.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth-century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth-Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938; High Collars & Monocles: 1920s Novels by British Female Couples.

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young Adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

Leave a Reply