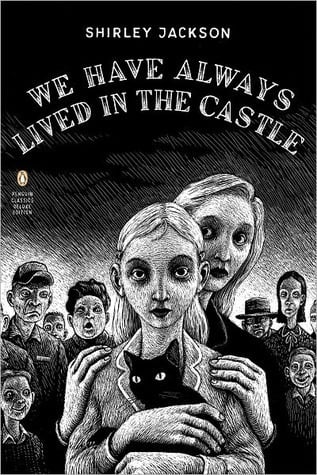

An Analysis of We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

By Francis Booth | On May 6, 2021 | Updated January 7, 2024 | Comments (4)

This analysis of We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962), Shirley Jackson’s last novel, has a special emphasis on Mary Katherine (Merricat), the younger of the Blackwood sisters central to the story.

Excerpted from Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid 20th Century Woman’s Novel by Francis Booth, reprinted by permission.

In Shirley Jackson’s The Sundial and The Haunting of Hill House, she used an old house as a brooding, malign presence in the novel, almost a character in its own right. She did the same, though in a completely different way, in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, her last completed novel.

“Shirley Jackson is a kind of Virginia Werewoolf among the séance-fiction writers. By day, amiably disguised as an embattled mother, she devotes her artful talents to the real-life confusions of the four small children (Life Among the Savages, Raising Demons) in her Vermont household.

But when shadows fall and the little ones are safely tucked in, Author Jackson pulls down the deadly nightshade and is off.

With exquisite subtlety she then explores a dark world (“The Lottery,” Hangsaman, The Haunting of Hill House) in which the usual brooding old houses, fetishes, poisons, poltergeists and psychotic females take on new dimensions of chill and dementia under her black-magical writing skill and infra-red feminine sensibility.” (Time Magazine, 1962)

A literary cousin of Natalie Waite & Cassandra Mortmain

We Have Always Lived in the Castle was well received at the time of its publication – the reception of Jackson’s books got warmer with each new one she published – and has been well-regarded ever since, generally being considered her best work.

But it is strange that little attention has been paid to the similarity in title and content to Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle; both are narrated by odd, isolated adolescent women living in fortress-like solitude, though Smith’s Cassandra Mortmain is perhaps more like Jackson’s Natalie Waite of Hangsaman than Merricat Blackwood.

Shirley Jackson’s previous adolescent heroines, including Natalie, have all been a little bit unhinged, but of this novel she said that the heroine was “really crazy.”

Jackson’s older daughter Jannie told her mother’s biographer Judy Oppenheimer that the character of Merricat was based on her younger sister Sally and the character of the older sister Constance was based on herself.

Introducing Merricat Blackwood

Jackson understood teenage girls and saw how really crazy they could be. In this case, the crazy girl is the narrator so that we see the story, indeed the whole world through her rather myopic, out of focus eyes. The opening paragraph is often quoted, and rightly so, as one of the best opening paragraphs in modern fiction; it is worth quoting again.

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. The rest of my family is dead.

Actually this is not completely true: her uncle Julian is not dead and still lives with them, though he is in a wheelchair and has advanced dementia – he never speaks to Merricat and seems to think she is dead, along with the rest of the family who used to live in the house.

It becomes apparent that the rest of the family have been poisoned and that Constance – ten years older than Merricat – was tried for their murder but not convicted.

. . . . . . . . .

Girls in Bloom is available on Amazon US and Amazon UK

Girls in Bloom in full on Issuu

. . . . . . . . .

Shunned by the villagers

The remaining three family members live in a large rambling house on the edge of the village (presumed to be based on the New England town of Bennington where the Jacksons lived; her husband taught at the local college, a prestigious school for girls at the time).

The inhabitants of the fictional village resented the old and wealthy family, who have lived in the house for generations, for their pretensions, and even more so after Merricat’s late father had fenced off the shortcut through the estate that the villagers used to use.

“The people of the village have always hated us.” Merricat is the only one who leaves the grounds of the house and only then twice a week to do the shopping and go to the library; Constance, who is an excellent gardener and cook gives her a shopping list.

Merricat gets through the shopping and comes home as quickly as possible, though she always briefly stops for coffee just to show that she does not care what people think, even though she does; whenever any of the surly and suspicious villagers come in they always taunt her. Merricat hates them in return.

Sympathetic magic

Merricat seems to have a degree of what would now be called OCD; whenever she leaves the house she plays a superstitious kind of children’s game of gaining and losing points depending on which route she can take.

“The library was my start and the black rock was my goal. I had to move down one side of Main Street, cross, and then move up the other side until I reached the black rock, when I would win. I began well, with a good safe turn along the empty side of Main Street, and perhaps this would turn out to be one of the very good days; it was like that sometimes, but not often on spring mornings. If it was a very good day I would later make an offering of jewelry out of gratitude.”

Merricat is superstitious to the point of believing in sympathetic magic; she buries objects and uses coins and mirrors to bring luck. She lives in her own private world, on the moon, as she puts it, though she does not mean this literally: “I am living on the moon, I told myself, I have a little house all by myself on the moon.”

Like all young girls she has a private world to which she can retreat in her head – taking with her cat Jonas, who acts as kind of a witch’s familiar; Jackson had written a non-fiction book the children about the Salem witch trials, where adults believed that young girls believed that they could harm people with sympathetic magic.

But of course Merricat is not a young girl, she is eighteen, even if she is mentally not even the twelve years old she was at the time of the death of her family.

Merricat and Constance

“I liked my house on the moon, and I put a fireplace in it and a garden outside (what would flourish, growing on the moon? I must ask Constance).” Constance, who is more like a loving mother than an older sister, always indulges Merricat in her fantasies.

Merricat and Constance are extremely fond of each other, complementing each other perhaps to the extent of being two halves of the same character; we have seen this several times in Girls in Bloom: two sisters with opposing personalities who are both to sides of the same coin.

“When I was small I thought Constance was a fairy princess … Even at the worst times she was pink and white and golden, and nothing has ever happened to dim the brightness of her. She is the most precious person in my world, always.”

In return, Constance loves and looks after Merricat with great affection and solicitude, sometimes calling her ‘silly Merricat’, but never chiding her or getting cross with her. It emerges that, before the poisoning, Merricat had been considered wayward and disobedient and had often been sent to bed with no supper, as she was on the night of the poisoning.

The remaining family members are quite content with their strange life, which they have lived for the six years since the poisoning. Uncle Julian never leaves the house, Constance never leaves the grounds and only leaves the house to tend to her garden; practically no one ever comes to visit them.

“Don’t you ever want to leave here, Merricat?” asks Constance. “Where would we go?” she replies. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.”

The two sisters are even fond of uncle Julian, who is happy enough pottering around taking notes and claiming to be writing a book about the poisoning, though he gets confused and very often has to ask if the poisoning actually happened.

The two sisters never talk about it and Merricat never reveals anything to us, but we are slowly coming to think that perhaps it was she who did the poisoning and not Constance.

. . . . . . . . .

A 1962 review of We Have Always Lived in the Castle

Six Novels by Shirley Jackson: Psychological Thrillers by a Master

. . . . . . . . .

The perfidy of cousin Charles

The finely balanced domestic harmony is shattered when the sisters’ cousin Charles comes to visit and seems intent on staying. Merricat had already foreseen something: “All the omens spoke of change.” Change of course being the last thing that Merricat wants; she never wants to come of age. “There’s a change coming,” she says to Constance. “It’s spring, silly,” she replies.

It is quickly apparent to us, if not to Merricat and Constance, that Charles is after their money: it seems that the father had had a large amount of money in his safe when the family all died. There are also many silver coins, which Merricat has buried for superstitious reasons.

“On Sunday mornings I examined my safeguards, the box of silver dollars I had buried by the creek, and the doll buried in the long field, and the book nailed to the tree in the pinewoods; so long as they were where I put them nothing could get in to harm us.”

Charles, who seems to be broke, becomes almost hysterical at this disregard of money but of course the two sisters are not concerned about money as such, they only need enough to live on; uncle Julian has no idea where the money comes from to provide the food that Constance prepares for him three times a day.

Merricat tries various kinds of sympathetic magic to get Charles to leave, but he is intent on staying and Constance seems to become almost fond of him. “It was important to choose the exact device to drive Charles away. An imperfect magic, or one incorrectly used, might only bring more disaster upon our house.”

Merricat tries everything, including not only symbolic magic like smashing mirrors but also practical attacks on him like pouring a pitcher of water over his bed. She even says to Constance: “I was thinking that you might make a gingerbread man, and I could name him Charles and eat him.”

This is a very similar idea of sympathetic magic to the “poppets” that the so-called Salem Witches used, as Jackson had said in her book on them and Arthur Miller showed in his play The Crucible of 1955.

There is even more explicit reference to this kind of magic when Merricat finds a stone the size of a head, draws a face on it, buries it in the ground and says, “Goodbye, Charles.” But Charles’ presence seems to be making Constance reconsider their life.

“I never realized until lately how wrong I was to let you and Uncle Julian hide here with me. We should have faced the world and tried to live normal lives; Uncle Julian should have been in a hospital all these years, with good care and nurses to watch him. We should have been living like other people. You should…” She stopped, and waved her hands helplessly. “You should have boyfriends,” she said finally, and then began to laugh because she sounded funny even to herself.

“I have Jonas,” I said, and we both laughed and Uncle Julian woke up suddenly and laughed a thin old cackle.

“You are the silliest person I ever saw,” I told Constance, and went off to look for Jonas.

. . . . . . . . .

We Have Always Lived in the Castle (2019 film)

. . . . . . . .

Up in flames

Merricat is appalled at the way Charles brings newspapers into the house; they have no phone, never open mail and have received no news since Constance was released from prison.

Another of Charles’ annoying habits for Merricat is his pipe-smoking, which leaves smell and mess in the pristine house – ever since the poisoning the two sisters have “neatened” the house weekly, leaving everything undisturbed and as it was when the whole family was living there.

She finds a saucer with his burning pipe on it; “I brushed the saucer and the pipe of the table into the wastebasket and they fell softly onto the newspapers he had brought into the house.’ If it does occur to her that this will cause a fire, she does not tell us. But of course it does cause a fire.

The local fire brigade attend, though all the neighbors stand around watching and tell them to let it burn. The villagers then go in to the house and start smashing objects and breaking windows in a frenzy of hatred that again recalls the days of witch hunting; the burning of “witches” – the auto da fé or act of faith – was supposed to free their souls.

Uncle Julian dies in the fire and Charles leaves but the two sisters remain in what is left of the house, which is pretty much only the kitchen. “Our house was a castle, turreted, and open to the sky.” (This makes their house even more like Cassandra Mortmain’s castle.)

They decide that they will continue their lives as before; the kitchen was the centre of their existence anyway. They have no clothes, as everything has been destroyed, but Constance says she will wear uncle Julian’s shirts, which have survived and Merricat will wear a tablecloth made into a dress.

There is preserved food in the cellar, and the garden, though covered in ash, will still produce fresh food for them. They board up the door so that no one can see in, now that the village children have started to play on the path that their father had blocked off.

And then, after only a few days, villagers start to leave food outside the door with apology notes for their behavior; they will not starve and they have each other.

One of our mother’s Dresden figurines is broken, I thought, and I said aloud to Constance, “I am going to put death in all their food and watch them die.”

Constance stirred, and the leaves rustled. “The way you did before?” she asked.

It had never been spoken of between us, not once in six years.

“Yes,” I said after a minute, “the way I did before.”

This is the nearest Merricat comes to a coming of age moment: admitting guilt and taking responsibility for her actions, though she does not have any regret. “Although I did not perceive it then, time and the orderly pattern of our old days had ended.” The new Merricat accepts the changes; she stops believing in the power of magic and turns more practical things.

“My new magical safeguards were the lock on the front door, and the boards over the windows, and the barricades along the sides of the house … We were going to be very happy, I thought. There were a great many things to do, and a whole new pattern of days to arrange, but I thought we were going to be very happy.”

. . . . . . . .

Contributed by Francis Booth, the author of several books on twentieth century culture:

Amongst Those Left: The British Experimental Novel 1940-1960 (published by Dalkey Archive); Everybody I Can Think of Ever: Meetings That Made the Avant-Garde; Girls in Bloom: Coming of Age in the Mid-Twentieth Century Woman’s Novel; Text Acts: Twentieth Century Literary Eroticism; and Comrades in Art: Revolutionary Art in America 1926-1938

Francis has also published several novels: The Code 17 series, set in the Swinging London of the 1960s and featuring aristocratic spy Lady Laura Summers; Young adult fantasy series The Watchers; and Young adult fantasy novel Mirror Mirror. Francis lives on the South Coast of England.

This analysis really deepens my understanding of Shirley Jackson’s work! I appreciate how you highlighted the themes of isolation and the complexities of family dynamics in “We Have Always Lived in the Castle.” The way you connected Merricat’s perspective to the broader societal commentary was particularly insightful. Can’t wait to reread the book with this new lens!

I found this analysis to be incredibly thought-provoking and insightful. The way the author broke down the themes of isolation and the blurring of reality in the novel really resonated with me. I had never considered the mirror as a symbol of the main character’s disconnection from the outside world, but now I can’t help but see it everywhere. The conclusion about the novel being a critique of the patriarchal society was also spot on. Thank you for sharing your expertise and insights!

I think one of the hallmarks of Jackson’s great writing is that she simply induces us to sympathize with Merricat from the first paragraph. Is there anything sympathetic about someone who poisoned their own family, is functionally anti-social and, one would suspect, insane — and yet we do sympathize with her without question. Shirley Jackson is one of our masterful writers in any genre!

Thank you, Grace, and I completely agree — if anything, Shirley Jackson is under-rated, and she should be read and appreciated a lot more!