Aurora Leigh by Elizabeth Barrett Browning: A 19th-Century Analysis

By Nava Atlas | On February 7, 2023 | Updated February 18, 2023 | Comments (0)

In 1856, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh, a long narrative novel in verse, was published. It would become one of her best known works, and a true magnum opus with 11,000 lines.

The story of a writer somewhat like herself, it’s set in a lush landscape and laced with Elizabeth’s wry observations on the position of women in her time and place.

In a book titled Some Eminent Women of Our Time (1889), the author observed:

“The work for which the world is most deeply in her debt is Aurora Leigh. It probes to the bottom, but with a hand guided by purity and justice, those social problems which lie at the root of what are known as women’s questions.

Her intense feeling that the honor of manhood can never be reached while the honor of womanhood is sullied; her no less profound conviction that people can never be raised to a higher level by mere material prosperity, make this book one of the most precious in our language.

She herself speaks of it in the dedication as ‘The most mature of my works, and the one into which my highest convictions upon Life and Art have entered.’ If she had written nothing else, she would stand out as one of the epoch-making poets of the present century.”

And Kathleen Blake wrote in this contemporary view on Victorian Web:

“Aurora Leigh is a ‘verse novel’ in blank verse and nine books, longer than Paradise Lost, and it offers a comprehensive treatment of E.B.B.’s complicated feelings about love … Aurora Leigh assumes a feminine instinct of love, from which it develops the woman artist’s dilemma: she cannot become a full artist unless she is a full woman, but she can hardly become an artist at all without resisting love as it consumes women, subsuming them to men.”

Read the rest of this excellent analysis, and find the full text of Aurora Leigh.

. . . . . . . . . . .

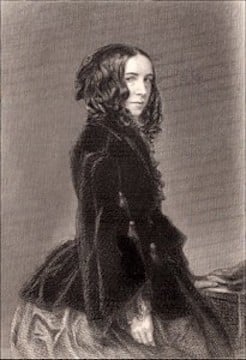

Learn about Elizabeth Barrett Browning

. . . . . . . . . . .

The following analysis of Aurora Leigh by Elizabeth Barrett Browning is excerpted from Essays by Arthur Christopher Benson, published by William Heinemann (London), 1896.

Rich in insights and references to other poets of the period, this essay and the book from which it came are in the public domain.

This analysis of Aurora Leigh is a portion of a larger analysis of the poetry of Elizabeth Browning by this author.

A 19th-century analysis of Aurora Leigh

We turn to Mrs. Browning’s most important and most characteristic work, Aurora Leigh. Unfortunately its length alone, were there not any other reasons, would prevent its ever being popular.

Ten thousand lines of blank verse is a serious thing. The fact that the poem is to a great extent autobiographical, combined with the comparative mystery in which the authoress was shrouded and the romance belonging to a marriage of poets — these elements are enough to account for the general enthusiasm with which the poem was received.

Walter Savage Landor said that it made him drunk with poetry — that was the kind of expression that its admirers allowed themselves to make use of with respect to it. And yet in spite of these credentials, the fact remains that it is a difficult volume to work through.

A romance with an intricate plot

It is the kind of book that one begins to read for the first time with intense enjoyment, congratulating oneself after the first hundred pages that there are still three-hundred to come.

Then the mood gradually changes; it becomes difficult to read without a marker; and at last it goes back to the shelf with the marker about three-fourths of the way through. As she herself wrote,

The prospects were too far and indistinct.

’Tis true my critics said “A fine view that.”

The public scarcely cared to climb my book

For even the finest;—and the public’s right.

Now what is the reason of this? In the first place it is a romance with a rather intricate plot, and a romance requires continuous reading and cannot be laid aside for a few days with impunity.

Secondly, it requires hard and continuous study; there is hardly a page without two or three splendid thoughts, and several weighty expressions; it is a perfect mine of felicitous though somewhat lengthy quotations upon almost every question of art and life, yet it is sententious without being exactly epigrammatic.

Thirdly, it is very digressive, distressingly so when you are once interested in the story. Lastly, it is not dramatic; whoever is speaking, Lord Howe, Aurora, Romney Leigh, Marian Earle, they all express themselves in a precisely similar way; it is even sometimes necessary to reckon back the speeches in a dialogue to see who has got the ball.

In fact it is not they who speak, but Mrs. Browning. To sum up, it is the attempted union of the dramatic and meditative elements that is fatal to the work from an artistic point of view.

. . . . . . . . . .

You may also enjoy:

“A Dead Rose”: An Ecocritical Reading

. . . . . . . . . .

Attempting to disentangle the poem’s motive

Perhaps, if we are to try and disentangle the motive of the whole piece, to lay our finger on the main idea, we may say that it lies in the contrast between the solidity and unity of the artistic life, as opposed to the tinkering philanthropy of the Sociologist.

Aurora Leigh is an attempt from an artistic point of view to realize in concrete form the truth that the way to attack the bewildering problem of the nineteenth century, the moral elevation of the democracy, is not by attempting to cure in detail the material evils, which are after all nothing but the symptoms of a huge moral disease expressing itself in concrete fact, but by infusing a spirit which shall raise them from within.

To attack it from its material side is like picking off the outer covering of a bud to assist it to blow, rather than by watering the plant to increase its vitality and its own power of internal action.

In fact, as our clergy are so fond of saying, a spiritual solution is the only possible one, with this difference, that in Aurora Leigh this attempt is made not so much from the side of dogmatic religion as of pure and more general enthusiasms.

The insoluble enigma is unfortunately, whether, under the pressure of the present material surroundings, there is any hope of eliciting such an instinct at all; whether it is not actually annihilated by want and woe and the diseased transmission of hereditary sin.

The challenge of presenting quotations from the poem

It is of course totally impossible to give any idea of a poem of this kind by quotations, partly, too, because as with most meditative poetry, the extracts are often more impressive by themselves than in their context, owing to the fact that the run of the poem is interfered with rather than assisted by them.

But we may give a few specimens of various kinds. “I,” she says,

Will write my story for my better self,

As when you paint your portrait for a friend

Who keeps it in a drawer, and looks at it

Long after he has ceased to love you, just

To hold together what he was and is.

This is one of those mysterious, sudden images that take the fancy; she is describing the high edge of a chalk down:

You might see

In apparition in the golden sky

… the sheep run

Along the fine clear outline, small as mice

That run along a witch’s scarlet thread.

And this is a wonderful rendering of the effect, which never fails to impress the thought, of the mountains of a strange land rising into sight over the sea’s rim:

I felt the wind soft from the land of souls;

The old miraculous mountain heaved in sight

One straining past another along the shore

The way of grand, tall Odyssean ghosts,

Athirst to drink the cool blue wine of seas

And stare on voyagers.

We may conclude with this enchanting picture of an Italian evening:

Fire-flies that suspire

In short soft lapses of transported flame

Across the tingling dark, while overhead

The constant and inviolable stars

Outrun those lights-of-love: melodious owls

(If music had but one note and was sad,

‘Twould sound just so): and all the silent swirl

Of bats that seem to follow in the air

Some grand circumference of a shadowy dome

To which we are blind; and then the nightingales

Which pluck our heart across a garden-wall,

(When walking in the town) and carry it

So high into the bowery almond-trees

We tremble and are afraid, and feel as if

The golden flood of moonlight unaware

Dissolved the pillars of the steady earth,

And made it less substantial.

It would seem in studying Mrs. Browning’s work as though either she herself or her advisers did not appreciate her special gift.

More poetry by Elizabeth Barrett Browning on this site

- “To George Sand: A Desire”

- “To Flush, My Dog”

- “The Cry of the Children”

- “Mother and Poet”

- 10 Shorter Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poetic Genius

Leave a Reply