A Dead Rose by Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Ecocritical Reading

By Jason Horn | On June 11, 2017 | Updated February 7, 2023 | Comments (0)

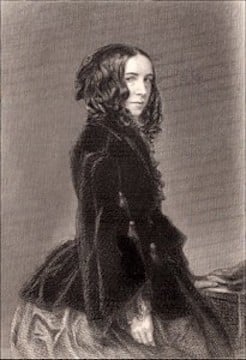

Elizabeth Barrett Browning is perhaps best known for Sonnet 43. It opens with the infamously sappy line: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.” Spoiler alert: there are ten ways.

Browning enjoyed much popular and critical success in her life, which continued for some time after her death in 1861, at age 55. Her popularity declined over much of the twentieth century, until interest in it was revived by new biographies and scholarly editions of her works.

Though celebrated for ‘Sonnet 43’, which cold-hearted cynics like myself see as trite and kitschy, the poem “A Dead Rose” (see below) is perhaps more indicative of the talent that made her famous.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Elizabeth Barrett Browning

. . . . . . . . . . .

An ecocritical or ecofeminist reading

The poem, though conventional in its metre and rhyme scheme, and though it makes excessive use of the word ‘thee’ (it appears 21 times in the poem, making up 8.4% of the words in the poem and appearing an average of 2.6 times per quatrain), offers a multiplicity of readings to a contemporary audience.

While many have seen the poem as an analogy for aging, or perhaps for illness (Browning herself was extremely ill in her later years), its most insightful contemporary reading is perhaps an ecocritical or ecofeminist one.

In addressing the poem to a rose, Browning makes the natural realm the subject of the love poem, replacing the traditional human subject of a love poem with one of nature’s denizens, and by contrasting the nurturing environment of nature with humanity’s fatal disregard of nature, the poem ultimately highlights the faults of humanity’s anthropocentric views.

Nature as subject, mentor, and central figure

As an analogy for aging or disability, it also presents nature as a mentor and exploits the pedagogical benefits of ecological metaphors. In this way, the poem challenges humanity’s anthropocentric paradigm, providing a prophetic encapsulation of flaws that define humanity’s current relationships with nature.

In making the poem about a representative of the natural realm, Browning shifts the more conventional subject of the poem from the human realm to the natural realm, thereby encouraging a shift away from humanity’s anthropocentric views.

This approach is made overtly obvious with the poem’s first two words: “O Rose!” Browning’s use of capitalization and punctuation draws the reader’s attention to her emphasis, as she both capitalized the word ‘Rose’, making it a proper name and not simply a noun/subject, and then places an emphatic exclamation mark where a comma would have typically been used. In this way she emphasizes the poem’s subject before the reader has even reached the third word.

Having nature as the subject also makes nature the central figure, and therefore the priority, rather than a figure from the human realm. The anthropomorphic implications of the apostrophe are perpetuated by poet’s employment of personification, as Browning also describes the sun as a ‘he’, writing that he mixed “his glory in [the rose’s] glorious urn.”

The pairing of apostrophe and personification disputes the typically anthropocentric approach for poetry, romantic poetry in particular. In this way Browning makes it clear that she is elevating nature above humanity.

Excerpted and adapted from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “A Dead Rose: A Prophetic Environmental Warning” on Literary Ramblings. Read the rest of Jason Horn’s analysis of A Dead Rose, and the poem itself, below:

A Dead Rose

O Rose! who dares to name thee?

No longer roseate now, nor soft, nor sweet;

But pale, and hard, and dry, as stubble-wheat, —

Kept seven years in a drawer —thy titles shame thee.

The breeze that used to blow thee

Between the hedgerow thorns, and take away

An odour up the lane to last all day, —

If breathing now, —unsweetened would forego thee.

The sun that used to smite thee,

And mix his glory in thy gorgeous urn,

Till beam appeared to bloom, and flower to burn, —

If shining now, —with not a hue would light thee.

The dew that used to wet thee,

And, white first, grow incarnadined, because

It lay upon thee where the crimson was, —

If dropping now, —would darken where it met thee.

The fly that lit upon thee,

To stretch the tendrils of its tiny feet,

Along thy leaf’s pure edges, after heat, —

If lighting now, —would coldly overrun thee.

The bee that once did suck thee,

And build thy perfumed ambers up his hive,

And swoon in thee for joy, till scarce alive, —

If passing now, —would blindly overlook thee.

The heart doth recognise thee,

Alone, alone! The heart doth smell thee sweet,

Doth view thee fair, doth judge thee most complete, —

Though seeing now those changes that disguise thee.

Yes, and the heart doth owe thee

More love, dead rose! than to such roses bold

As Julia wears at dances, smiling cold! —

Lie still upon this heart —which breaks below thee!

. . . . . . . . . . .

Aurora Leigh: A 19th-Century Analysis To George Sand: A Desire

To George Sand: A Desire

. . . . . . . . . .

Leave a Reply