10 Shorter Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poetic Genius

By Taylor Jasmine | On December 15, 2020 | Updated February 18, 2023 | Comments (1)

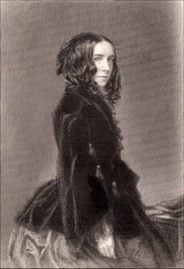

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861) was a respected and widely read British poet of the Victorian era. Tragedy and loss as well as great love marked her life. Many of her poems were incredibly long, some even book-length (like Aurora Leigh); this post will touch on some of the shorter poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

Their relative brevity (for some aren’t actually that short) in no way diminishes the genius of their author.

Elizabeth Barrett, who enjoyed a cultured and privileged upbringing in England, began writing poetry in earnest before even reaching her teens. She was introduced to British literary society by her cousin, John Kenyan in the 1830s, and soon, her individual poems were becoming known and respected in these circles.

From Lives of Girls Who Became Famous by Sarah K. Bolton (1886 / 1914):

“When she was twenty-nine, Elizabeth published The Seraphim and Other Poems. The Seraphim was a reverential description of two angels watching the Crucifixion. Though the critics saw much that was strikingly original, they condemned the frequent obscurity of meaning and irregularity of rhyme.

The next year, The Romaunt of the Page and other ballads appeared, and in 1844, when she was thirty-five, a complete edition of her poems, opening with the Drama of Exile.”

Her first collection, Poems (1844) was an immediate success in Europe and the U.S. and made her famous. A Drama of Exile: and Other Poems (1845) cemented her reputation.”

In addition to the poems in this post, you’ll also find individual posts featuring poems that are longer or that are teamed with further discussion.

Here is the selection of poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning ahead in this post. A link to an analysis follows each poem.

The Lady’s Yes

My Heart and I

A Man’s Requirements

A Musical Instrument

Grief

Love

The Soul’s Expression

Patience Taught by Nature

Cheerfulness Taught by Reason

How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43)

Book-length poetical works by Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s famed Sonnet 43, at the end of this post, is the final portion of Sonnets from the Portuguese, which you can read here in full.

- A generous posthumous collection of her poetry, The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning in Six Volumes (1890) can be found on Project Gutenberg. It includes her book-length Casa Guidi Windows.

- Aurora Leigh, a book-length poetical work, can also be found on Project Gutenberg.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Lady’s Yes

“Yes!” I answered you last night;

“No!” this morning, Sir, I say!

Colours, seen by candle-light,

Will not look the same by day.

When the tabors played their best,

Lamps above, and laughs below —

Love me sounded like a jest,

Fit for Yes or fit for No!

Call me false, or call me free —

Vow, whatever light may shine,

No man on your face shall see

Any grief for change on mine.

Yet the sin is on us both —

Time to dance is not to woo —

Wooer light makes fickle troth —

Scorn of me recoils on you!

Learn to win a lady’s faith

Nobly, as the thing is high;

Bravely, as for life and death —

With a loyal gravity.

Lead her from the festive boards,

Point her to the starry skies,

Guard her, by your truthful words,

Pure from courtship’s flatteries.

By your truth she shall be true —

Ever true, as wives of yore —

And her Yes, once said to you,

SHALL be Yes for evermore.

. . . . . . . . . . .

My Heart and I

I.

ENOUGH! we’re tired, my heart and I.

We sit beside the headstone thus,

And wish that name were carved for us.

The moss reprints more tenderly

The hard types of the mason’s knife,

As heaven’s sweet life renews earth’s life

With which we’re tired, my heart and I.

II.

You see we’re tired, my heart and I.

We dealt with books, we trusted men,

And in our own blood drenched the pen,

As if such colours could not fly.

We walked too straight for fortune’s end,

We loved too true to keep a friend;

At last we’re tired, my heart and I.

III.

How tired we feel, my heart and I!

We seem of no use in the world;

Our fancies hang grey and uncurled

About men’s eyes indifferently;

Our voice which thrilled you so, will let

You sleep; our tears are only wet :

What do we here, my heart and I?

IV.

So tired, so tired, my heart and I!

It was not thus in that old time

When Ralph sat with me ‘neath the lime

To watch the sunset from the sky.

Dear love, you’re looking tired,’ he said;

I, smiling at him, shook my head :

‘Tis now we’re tired, my heart and I.

V.

So tired, so tired, my heart and I!

Though now none takes me on his arm

To fold me close and kiss me warm

Till each quick breath end in a sigh

Of happy languor. Now, alone,

We lean upon this graveyard stone,

Uncheered, unkissed, my heart and I.

VI.

Tired out we are, my heart and I.

Suppose the world brought diadems

To tempt us, crusted with loose gems

Of powers and pleasures? Let it try.

We scarcely care to look at even

A pretty child, or God’s blue heaven,

We feel so tired, my heart and I.

VII.

Yet who complains? My heart and I?

In this abundant earth no doubt

Is little room for things worn out :

Disdain them, break them, throw them by

And if before the days grew rough

We once were loved, used, — well enough,

I think, we’ve fared, my heart and I.

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Man’s Requirements

I.

Love me Sweet, with all thou art,

Feeling, thinking, seeing;

Love me in the lightest part,

Love me in full being.

II.

Love me with thine open youth

In its frank surrender;

With the vowing of thy mouth,

With its silence tender.

III.

Love me with thine azure eyes,

Made for earnest granting;

Taking colour from the skies,

Can Heaven’s truth be wanting?

IV.

Love me with their lids, that fall

Snow-like at first meeting;

Love me with thine heart, that all

Neighbours then see beating.

V.

Love me with thine hand stretched out

Freely—open-minded:

Love me with thy loitering foot,—

Hearing one behind it.

VI.

Love me with thy voice, that turns

Sudden faint above me;

Love me with thy blush that burns

When I murmur Love me!

VII.

Love me with thy thinking soul,

Break it to love-sighing;

Love me with thy thoughts that roll

On through living—dying.

VIII.

Love me when in thy gorgeous airs,

When the world has crowned thee;

Love me, kneeling at thy prayers,

With the angels round thee.

IX.

Love me pure, as musers do,

Up the woodlands shady:

Love me gaily, fast and true

As a winsome lady.

X.

Through all hopes that keep us brave,

Farther off or nigher,

Love me for the house and grave,

And for something higher.

XI.

Thus, if thou wilt prove me, Dear,

Woman’s love no fable.

I will love thee—half a year—

As a man is able.

Analysis of “A Man’s Requirements”

. . . . . . . . . . .

A Musical Instrument

I.

WHAT was he doing, the great god Pan,

Down in the reeds by the river?

Spreading ruin and scattering ban,

Splashing and paddling with hoofs of a goat,

And breaking the golden lilies afloat

With the dragon-fly on the river.

II.

He tore out a reed, the great god Pan,

From the deep cool bed of the river :

The limpid water turbidly ran,

And the broken lilies a-dying lay,

And the dragon-fly had fled away,

Ere he brought it out of the river.

III.

High on the shore sate the great god Pan,

While turbidly flowed the river;

And hacked and hewed as a great god can,

With his hard bleak steel at the patient reed,

Till there was not a sign of a leaf indeed

To prove it fresh from the river.

IV.

He cut it short, did the great god Pan,

(How tall it stood in the river!)

Then drew the pith, like the heart of a man,

Steadily from the outside ring,

And notched the poor dry empty thing

In holes, as he sate by the river.

V.

This is the way,’ laughed the great god Pan,

Laughed while he sate by the river,)

The only way, since gods began

To make sweet music, they could succeed.’

Then, dropping his mouth to a hole in the reed,

He blew in power by the river.

VI.

Sweet, sweet, sweet, O Pan!

Piercing sweet by the river!

Blinding sweet, O great god Pan!

The sun on the hill forgot to die,

And the lilies revived, and the dragon-fly

Came back to dream on the river.

VII.

Yet half a beast is the great god Pan,

To laugh as he sits by the river,

Making a poet out of a man :

The true gods sigh for the cost and pain, —

For the reed which grows nevermore again

As a reed with the reeds in the river.

Analysis of “A Musical Instrument”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Grief

I tell you, hopeless grief is passionless;

That only men incredulous of despair,

Half-taught in anguish, through the midnight air

Beat upward to God’s throne in loud access

Of shrieking and reproach. Full desertness,

In souls as countries, lieth silent-bare

Under the blanching, vertical eye-glare

Of the absolute heavens. Deep-hearted man, express

Grief for thy dead in silence like to death—

Most like a monumental statue set

In everlasting watch and moveless woe

Till itself crumble to the dust beneath.

Touch it; the marble eyelids are not wet:

If it could weep, it could arise and go.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Love

We cannot live, except thus mutually

We alternate, aware or unaware,

The reflex act of life: and when we bear

Our virtue onward most impulsively,

Most full of invocation, and to be

Most instantly compellant, certes, there

We live most life, whoever breathes most air

And counts his dying years by sun and sea.

But when a soul, by choice and conscience, doth

Throw out her full force on another soul,

The conscience and the concentration both make

mere life, Love. For Life in perfect whole

And aim consummated, is Love in sooth,

As nature’s magnet-heat rounds pole with pole.

. . . . . . . . . . .

The Soul’s Expression

With stammering lips and insufficient sound

I strive and struggle to deliver right

That music of my nature, day and night

With dream and thought and feeling interwound

And only answering all the senses round

With octaves of a mystic depth and height

Which step out grandly to the infinite

From the dark edges of the sensual ground.

This song of soul I struggle to outbear

Through portals of the sense, sublime and whole,

And utter all myself into the air:

But if I did it,—as the thunder-roll

Breaks its own cloud, my flesh would perish there,

Before that dread apocalypse of soul.

Analysis of “The Soul’s Expression”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Patience Taught by Nature

“O Dreary life!” we cry, “O dreary life!”

And still the generations of the birds

Sing through our sighing, and the flocks and herds

Serenely live while we are keeping strife

With Heaven’s true purpose in us, as a knife

Against which we may struggle. Ocean girds

Unslackened the dry land: savannah-swards

Unweary sweep: hills watch, unworn; and rife

Meek leaves drop yearly from the forest-trees,

To show, above, the unwasted stars that pass

In their old glory. O thou God of old!

Grant me some smaller grace than comes to these;—

But so much patience, as a blade of grass

Grows by contented through the heat and cold.

Analysis of “Patience Taught by Nature”

. . . . . . . . . . .

Cheerfulness Taught by Reason

I think we are too ready with complaint

In this fair world of God’s. Had we no hope

Indeed beyond the zenith and the slope

Of yon gray blank of sky, we might be faint

To muse upon eternity’s constraint

Round our aspirant souls. But since the scope

Must widen early, is it well to droop,

For a few days consumed in loss and taint?

O pusillanimous Heart, be comforted,—

And, like a cheerful traveller, take the road—

Singing beside the hedge. What if the bread

Be bitter in thine inn, and thou unshod

To meet the flints?—At least it may be said,

“Because the way is short, I thank thee, God!”

Analysis of “Cheerful Taught by Reason”

. . . . . . . . . . .

How do I love thee? (Sonnet 43)

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

This is a wonderful analysis of Elizabeth poems. it provides enlightenment . to interested readers