Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh

By Marcie McCauley | On November 4, 2021 | Updated August 25, 2022 | Comments (0)

It’s still so relevant—a writer with her mouth “open in horror all the time” at “the state of the world” and all the “social injustice, prejudice, and poverty” around her. That’s how Louise Fitzhugh describes feeling in the mid-1970s—toward the end of her life, in a letter to a friend—in Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy (2020), a biography by Leslie Brody.

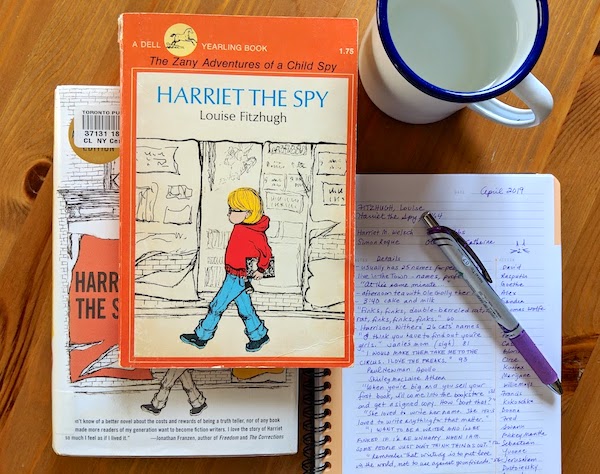

In the five years following its publication in 1964, Harriet the Spy sold about 2.5 million copies; that number nearly doubled by 2019. Decades have passed, but she remains relevant: readers continue to freshly fall for—and renew their acquaintance with—Harriet.

Leslie Brody did not grow up with Harriet; she “met” her when she was commissioned to adapt the novel for the stage in 1988: “I read it through several times, stunned at how lucky I was—after all this time, and the many ways our rendezvous might have gone awry—to find her.”

Louise Fitzhugh herself, conceived of Harriet in 1963, in the wake of disappointment after a gallery showing of her artwork: that’s when she started work on a children’s book featuring “a nasty little girl who keeps a notebook on all her friends.”

This disclosure is also from one of Louise Fitzhugh’s letters; Leslie Brody’s access to the author’s personal correspondence (and Brody’s own correspondence with Fitzhugh’s friends) fuels readers’ senses of intimate knowledge and understanding. It makes this biography feel revelatory and authentic, like Leslie Brody has peeked inside Harriet’s—I mean, Louise’s—notebook.

. . . . . . . . .

More about Louise Fitzhugh

. . . . . . . . . .

Harriet’s enduring relevance

In the novel, even at eleven years old, Harriet was insistent on being Harriet: “Harriet was just so about a lot of things.” Her nursemaid Ole Golly introduces her to writers like Cowper, Emerson, James, and Wordsworth with his “inward eye which is the bliss of solitude” and encourages Harriet’s writing habit.

But it’s a fine line between being alone and being lonely and, when the subjects of Harriet’s notebook discover its contents, Harriet must broaden her understanding of perspective.

In the 50th anniversary edition of Harriet the Spy, novelist Rebecca Stead explains Harriet’s enduring relevance: “What Harriet learns—painfully, necessarily—is that she can’t let every thought or observation escape onto the page.

Some truths, Ole Golly explains … are just for ourselves. In other words, there are some kinds of loneliness we must learn to live with.” It’s challenging, it’s relatable.

Judy Blume is more succinct: “She had secrets; I had secrets. She was curious; I was curious.” Brody’s curiosity about Fitzhugh and her secrets fuels her biographical explorations; her gratitude for Harriet’s complexity infuses her research with enthusiasm. It’s both detail-oriented and narrative-driven.

It’s my favorite aspect of Sometimes You Have to Lie: the Harriet-ness of it all. Additional details are available in the endnotes and any readers with specific interests can employ the index, but Brody’s familiarity with—and respect for—Fitzhugh’s work adds a layer of satisfaction for Harriet fans.

Fitzhugh’s early years

In describing Fitzhugh’s younger years, for instance, Brody notes: “One of her favorite habits was sitting at the top of the stairs to listen in on the grown-ups at cocktail hour.” Biography devotees might find this interesting; Harriet fans will thrill to the glimpse of Harriet-in-young-Louise.

But I might have guessed this volume would prove fascinating for its Harriet-ness: the evolving relationships with agents and publishers, details about character names and journal-keeping and collaboration, other influential reading in Fitzhugh’s stacks (Harper Lee I might have anticipated, but Yeats?!), and decisions to pursue/abandon manuscripts featuring other characters in Harriet’s circle.

What I did not expect were the dedicated excavations of Louise Fitzhugh’s own circle of friends and colleagues (and lovers, both male and female), her privileged upbringing and parents’ personal histories, and the diverse nature of her creative pursuits.

Brody also devotes chapters to both Louise’s father (Millsaps Fitzhugh) and his privileged youth in Memphis, Tennessee, and her mother (Mary Louise Perkins) of Clarksdale, Mississippi. The court proceedings surrounding their divorce were concluded while Louise was very young, but they were so dramatic and scandalous that she would later learn all the details via archival newspaper coverage.

Even as a young reader, I understood that Harriet’s family possessed a status that mine did not, but I did not connect that to her author’s experiences.

. . . . . . . . . .

More about Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

. . . . . . . . .

College and bohemian years

The Fitzhugh family’s wealth created ample educational and social opportunities for Louise; although as she grew up, her interest in the former grew, she opted out of the latter. Her studies at Bard College “in the remarkably pretty Hudson River Valley” were as significant for providing “a radically different perspective on race, sex, and class” as for being “a peaceful refuge.” There, “the women of Bard wore ‘pants and jackets, lounging and smoking as men.’”

Before attending Bard, and “encountering some truly gifted poets” beginning with Jimmy Merrill, Louise herself had considered writing poetry. “It was never easy for her to dislodge her father’s acid observation that any literary work that wasn’t Tolstoy was hardly worth the trouble.”

She believed that “painting and poetry were at the top of the art pyramid, and that other forms of design and literature somehow counted for less.” (Even though I knew that Fitzhugh illustrated Harriet the Spy, Brody’s biography reveals how important drawing was for her.)

By 1950, Louise was living in Greenwich Village, “part of a bohemian enclave” as Brody describes it, which included people like writer Djuna Barnes, photographer Berenice Abbott, literary critic Anatole Broyard, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and her particularly close friends Marijane Meaker and Sandra Scoppettone.

Much of the group, as the playwright and author Jane Wagner characterized it, was a network of “successful, creative, pleasure loving, ambitious, knowledgeable lesbians.” There, Fitzhugh “felt a safety in numbers against the judgment of the world.”

In 1961 she illustrated Suzuki Beane, a story that Sandra Scoppettone wrote, in an “age when sophisticated take-offs and spoofs were in fashion,” a response to characters like Kay Thompson’s Eloise. Fitzhugh also tinkered with one-act plays, like “The Butcher Shop” and “The Luncheonette,” which were also titles of paintings that she had exhibited at the Hudson Park branch of the New York Public Library in 1956.

Over time, Brody observes that Fitzhugh “became increasingly interested in surrealism” and created “more overtly satirical and political drawings with pioneers and cowboys to comment on the ‘national infatuation with violence and acquisition.’”

Creating power on the page

Brody’s observation about Fitzhugh’s reading while she wrote Harriet the Spy seems a suitable summary of Fitzhugh’s writing overall: “What these works ‘all have in common is their investigation into how the powerful connive to take advantage of defenseless individuals or marginalized groups.’”

When Fitzhugh read up on her parents’ divorce proceedings, she persistently returned to the idea that she was an afterthought, relegated to the margins in a situation that fundamentally shaped her future.

In contrast, Harriet creates her own power on the page (although it’s unexpectedly reflected against herself as the story unfolds). She consistently struggles to be an individual and to maintain her truth. “Kids who felt they were different could read parts of their secret selves in Harriet, relate to her refusal to be pigeonholed or feminized, and cheer her instinct for self-preservation,” Brody writes.

. . . . . . . . .

Playing Town: Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy

. . . . . . . . .

Truth-building

I’m reminded of Michaela Coel’s Misfits (2021), which was in my stack alongside this biography. When she describes how a “misfit is one who looks at life differently” and also someone whom life looks at differently—not only do I think of Harriet but, now, also her author. (Who, ironically, was compelled to keep many secrets from public view, even as she expressed herself boldly in her personal life.)

Coel’s idea of a “misfit” is “cross-generational and crosses concepts of gender or culture,” and it’s characterized “by a desire for transparency, a desire to see another’s point of view.” It’s Harriet all over, as she peers from a place of safety to observe people’s lives unfolding around her, scribbling her observations in her notebook.

Throughout Fitzhugh’s books, she makes the case for “children’s liberation” most obviously in Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change. Along the way, as Brody observes, she provides “life-preserving strategies that children may employ in their power struggle with adults.”

It’s not just truth-telling, it’s truth-building: “Lying is one time-honored tactic; self-reliance is another.” Brody provides both insight and understanding, in focusing on the struggles and triumphs that fuelled Fitzhugh’s artistic career and infused her art and literature. While Harriet is recording the truths she observes around her, learning when and how to articulate them, she is shaping her unique understanding of the world and making a space for misfits, like her, in it.

Joan Williams said Louise believed “writing for children gave her a wonderful sense of doing good.” This sense is as evident in Leslie Brody’s biography as it is in Fitzhugh’s writing. I’m as much of a Harriet fan as I ever was.

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

Leave a Reply